6 Options for Ventilating Homes in Humid Climates

Ventilating homes in any climate has its challenges. In Duluth, Minnesota, it’s the extremely cold weather in winter, which leads to extremely dry air when you bring it indoors. In Phoenix, Arizona, it’s the extremely hot weather in summer, which leads to higher air conditioning costs. In Santa Monica, California, it’s the extremely mild weather year round, which leads to windows getting stuck in the open position after each time the house is painted. Ventilating homes in humid climates, however, is special.

It’s the humidity. We run our air conditioners in humid climates to keep the indoor humidity at a comfortable level, below 60% relative humidity. That works great on hot days, not as well on not-so-hot days. Then, when you bring outdoor air in to reduce the amount of other people’s air you rebreathe and improve your indoor air quality, you bring in a lot of water vapor, too. On a hot day, your air conditioner probably can handle it. On anything less, it’s going to be sticky inside.

That is, it’s going to be sticky if you don’t understand the proper method for ventilating homes in humid climates. Here’s my countdown of 6 ways you can ventilate a humid climate home. It starts with one option you should avoid, two methods that are OK if done properly, and ends with the three best options. (The numbers below aren’t wrong.)

6. Fans blowing in, out, or both

Mechanical ventilation simply means moving air with fans. A whole-house mechanical ventilation system moves air between indoors and outdoors to change the air in the house. The easiest way to provide this type of ventilation is to run fans that exhaust air from the house, supply air to the house, or both.

Exhaust-only ventilation is not a good idea in humid climates because it sucks warm, humid air into the building assemblies, which can lead to mold growth and moisture damage. Supply-only ventilation is only a little better. It does put the house under positive pressure, but you’re dumping warm, humid outdoor air right into the house. Yes, you can temper it by mixing it with indoor air before introducing it, but all the water vapor is still there.

A balanced system does both at the same rate. The lead photo shows a simple version of that type, although it’s not really an acceptable way to do long-term whole-house ventilation. The only advantage with it is that it minimizes pressure effects in the house, but you’re still putting humid air right into the house.

Pros. Cheap and simple.

Cons. Difficult to control indoor humidity.

5. Supply-only fan with humidistat

Positive pressure inside the house is better in humid climates, so the first improvement on a simple supply-only system is a supply-only system with a humidistat. The QuFresh fan by Air King and the Broan Fresh In fans do that. It allows you to set upper and lower limits of both temperature and humidity. When the outdoor air is outside the range you’ve set, the fan shuts off and waits until conditions improve to start ventilate again. Also, you can duct the supply air and dump it near a return vent so it gets conditioned and distributed to the house.

Pros. Inexpensive and simple. Doesn’t require connection with air conditioner. Better than just fans at controlling indoor humidity.

Cons. May lead to comfort problems and poorly distributed air, depending on how the outdoor air is introduced.

4. Central fan integrated supply

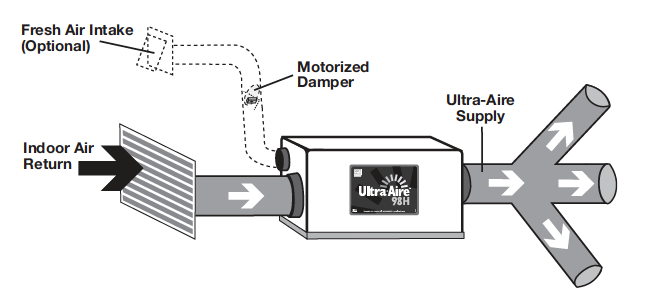

This system includes a controller, a duct connecting the return duct of the central air handler to the outdoors, and a motorized damper. You set it for how many minutes per hour you want the air handler to bring in outdoor air. When the heating or cooling system runs, the damper stays open until it hits the limit of minutes per hour. If the heating or cooling system don’t run enough, it turns on the blower, opens the motorized damper, and ventilates until it reaches the required amount of ventilation.

Pros. Inexpensive.

Cons. May be difficult to control indoor humidity on days when the air conditioner doesn’t run much. Requires connecting controlling with air handler.

1. Whole-house ventilating dehumidifier

In places like Sugarland, Texas, Kenner, Louisiana, and Sopchoppy, Florida, we often specify a ventilating dehumidifier in our HVAC design work. These units pull outdoor air in, dehumidify it, and then send the dry, fresh air into the house. We like the Santa Fe Ultra series whole-house dehumidifiers* because they’re the most efficient, made in America, and built to last. The best way to set them up is to have independent ducts, as shown below, but we do sometimes connect the ducts to the heating and air conditioning system when there’s not enough room for more ductwork.

Pros. Excellent way to control humidity and ventilate at the same time. Can be very quiet with the right equipment ducted properly. Inexpensive to operate if you choose a high-efficiency model. One piece of equipment for ventilating and dehumidifying.

Cons. High first cost.

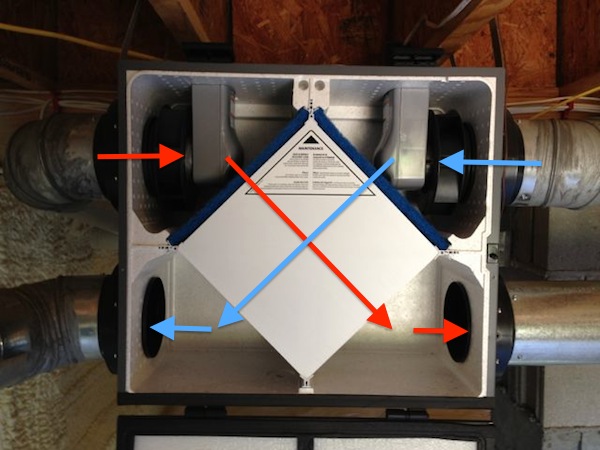

1. Energy recovery ventilator with supplemental dehumidification

An energy (technically enthalpy) recovery ventilator (ERV) has two air streams that exhange heat and moisture in a capillary core. The air streams don’t mix but allow the warmer air to give up a lot of its heat to the cooler air and the more humid air to give up a good amount of its moisture to the drier air. That way you don’t just send your expensive air outdoors without saving some of your investment. A common misconception, however, is that an ERV will reduce the humidity in a house. It doesn’t. An ERV is not a dehumidifier. It actually adds moisture to the house. It just adds less than you’d get without the recovery in an ERV. Within a year, I’ll have this type of system in my house, as I’m installing a Zehnder ERV and a Santa Fe Ultra dehumidifier.*

Pros. The ventilation happens with energy and moisture exchange, reducing the operating cost of ventilation. Excellent humidity control.

Cons. High first cost. Two pieces of mechanical equipment.

1. A conditioning ERV

Another great way of ventilating homes in humid climates is with what’s called a conditioning ERV. The CERV2 is made by Build Equinox, and their primary focus is indoor air quality. A similar system is made by Minotair. This equipment is kind of like an ERV with a heat pump, but it doesn’t have an ERV capillary core. It brings in outdoor air, exhausts indoor air, adds a little bit of heating or cooling when necessary, dehumidifies, filters, and recirculates. Read more about it in my article on ventilating with impunity.

Pros. Excellent humidity control and indoor air quality. Well-designed equipment.

Cons. High first cost. Complex equipment.

Ventilating homes in humid climates is challenging. The biggest issue is the humidity, so any ventilation system that doesn’t include dehumidification may well lead to comfort and indoor air quality problems. The last three of the six options above are the best and all include a way to dehumidify the air.

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard. He has a PhD in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

An Energy Recovery Ventilator Is NOT a Dehumidifier

We Need Higher Ventilation Rates. But How High?

4 Ways to Do Balanced Ventilation

* This is an affiliate link. You pay the same price you would pay normally, but Energy Vanguard may make a small commission if you buy after using the link.

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 15 Comments

Comments are closed.

Excellent article! I plan to share this with clients before we discuss their HVAC systems.

Great list, much needed.

With the ventilating dehumidifier option (e.g., Santa Fe/Ultra_Aire/April-Aire) your description maybe implies that the dehumidifer always runs when pulling in air that is more humid than the chosen set point in the house? I don’t know all the controls, but on mine (Ultra-Aire’s DEH 3000-R) ventilation and dehumidification are two different cycles. They might run at the same time or they might not. Which is to say that in this configuration (which is standard and described in their instructions) I don’t think they are sensing the humidity of the incoming air during ventilation and deciding whether or not to dehumidify. Rather the ventilation is just on a timer, and the dehumidification runs based on the overall RH of the house (well, the air near the sensor). As I say, I could be wrong about this, but the DEH 3000 manual does say, “The “VENT” setting controls the ventilation function of the system. It has

no control over the dehumidification function.” (p 13, https://www.santa-fe-products.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2020/03/Ultra-Aire-DEH-3000-3000R-Manual.pdf)

I don’t suppose it makes much difference in the end, although it is annoying to feel humid air injected, and one can hear that the dehumidifier is not running. This is less of a problem the more that the supply from the dehu is spread around (as ours is now ducted into the return of the central heat pump blower). And perhaps this arrangement is more efficient, given that the overall RH is the thing more is actually trying to manage (and maybe you want to vent with humid air if RH has fallen too low). But surely it would be more efficient to directly dehu vent air at 70% RH, rather than the mixed air at say 55% RH.

One last point: should these controls be managing RH or dewpoint? Your earlier writing implies dewpoint, although all those I’ve seen actually only allow specifying RH. Again, a small point 🙂

James, yeah, I didn’t go into detail about how the ventilation and dehumidification functions work, but you’re correct that a dehumidification call is based on the conditions where the sensor is and ventilation runs based on how you set it. The DEH 3000 senses the conditions where that controller is mounted, and the DEH 3000R is different only in that it uses a separate remote sensor.

Most ventilating dehumidifiers bring in a mix of recirculated air and ventilation air, so that helps the air coming out from feeling like straight outdoor air. That’s also why placement of the dehu supply vent is critical. You want that air to be well mixed with the indoor air by the time it reaches the people.

If you’re going to connect it to the heating & cooling ducts, the best place to dump the dehu supply air is into the supply side. Otherwise the AC dehumidifies less and your dehu runs more, using more energy overall. A lot of people dump it into the return because it seems natural to put it there since you want that air cooled in summer. But it’s better to put it into the supply. Be careful with duct sizing, though. More air means you may need bigger ducts and supply vents.

RH is fine for controlling the dehumidifier. My big problem with it is that it’s misused because you can’t talk about how humid the air really is by giving only the RH. No, I have to tell people, I don’t think it was 95° F and 95% RH, not at the same time anyway.

Your point about the venting dehu pulling both from its (re-circulating) return and its outside air-supply and therefore doing substantial mixing make sense. The 98H (just as an example) has a much larger return (10″ duct, I think) than the outside supply (6″ duct, I think), so I guess one is only seeing something in the realm of 40% outside air (6/16). Perhaps that was mostly a perception of feeling that the supply air during venting was quite humid 🙂

I know that there is some discussion on the location of the dehu supply when integrating with the AC ducting. FWIW, I discussed supply vs return mounting with my contractor and he was dead set against “supply to supply” on the basis that they’d had trouble with the pressure from the big AC blower outcompeting the blower on the dehu and meaning that the back-flow damper wouldn’t open fully, meaning less dehu air (aka higher static pressure in the dehu ducting) and whistling noises. Others don’t seem to have this issue (Corbin at Home Performance Channel tested and was satisfied that wouldn’t be a problem in his install). Just mentioning it because it doesn’t seem to come up in most discussions. Anyway, that’s how we ended up with a dehu supply to AC return configuration. We do appreciate not noticing the heated air from the dehu at all (we previously had a dedicated ducting system just for the dehu and even with careful placement the heated air was quite noticeable). We love having the dehu.

Yeah, it can be tricky to put two positive pressure ducts together. Instead of a 90° tee, sending the dehu supply air into the AHU supply through a 45° takeoff so the air enters in the direction of the flow does work.

Ken Gehring of Therma-Stor, the manufacturer of Santa Fe/Ultra dehumidifiers, gave a talk at Building Science Summer Camp in 2016 on the reasoning behind dumping into the supply. You can download his slides here:

Lazy Air Conditioning, by Ken Gehring (pdf)

Curious where you put the supplemental dehumidifier in the ERV scenario? I’m installing my ERV now and realize I need the dehumidifier also. I only have a typical Frigidaire basement unit now. We moved in our new construction in January and have an Awair IAQ monitor. The VOCs were not a big issue until a recently couch and chair purchase. I chair is leather and boom VOCs skyrocketed. So the ERV install became a priority.

Lee, independent ducting is the ideal way to do both the ERV and the dehumidifier. If you’re going to connect ERV and dehumidifier ducts to the heating and cooling ducts, see this article by David Treleven at Green Building Advisor:

Ductwork for ERVs, Dehumidifiers, and Forced-Air Heating Systems

Allison,

Thanks for the article link. I think I have a plan. I’ll run a separate ERV duct up the AC supply duct just under the register. That way there should be very little effect when both systems operate. I’ll use a cape type BD damper on the ERV duct so that conditioned air doesn’t run backwards into the ERV when its not running. The dehumidifier will just operate in the basement for now to see if it will take care of the whole house before I invest in the whole house unit. Until I’m thinking about taking the dehumidifier discharge to the HPWH intake and then taking the HPWH discharge and dumping it through the floor below the refrigerator (then I’ll just need to synchronize them for simultaneous operation).

You didn’t mention placement of the fresh air intake. May seem like an obvious thing – but the one here is placed in the rim joist, way too close to the dry soil/mulch under the roof overhang. Filters get dirty quickly. Placing a paver under it doesn’t help much. I would prefer placement in the roof or soffit.

I’ve also experienced leaking refrigerant in 70H units. Three in a row have failed. While the company has been honoring the warranty, it’s expensive to replace the unit every couple of years, even more expensive to have it recharged.

While considering alternatives, the current 70H is functioning only as a fresh air provider, with a separate dehumidifier operating in the basement. Being in upstate NY nearish Buffalo, humidity is high and fluctuates wildly.

framistat, I focused on different types of ventilation systems here. There are many design details to address to have a ventilation system that functions well. Your problem with the intake is one. Other commenters have raised issues about ducting and where the RH readings are taken.

That’s unfortunate about your trouble with the Ultra-Aire 70H. I wonder why yours are failing so frequently. What have their warranty folks said about it?

I forwarded my email conversation with their customer support to you; read it bottom to top. Basically, local HVAC no longer sells – or supports – these units because they leak.

Although viewed as complicated in residences or viewed as throwing money out an open window it should be mentioned that most of you second choice systems listed above would benefit comfort-wise from the addition of sensible heat after the mechanical cooling.

I have what I think should be a relatively straight-forward situation. Home around 1600 sq ft. ducting under the house for the most part with returns going through the attic. And a feed going through the attic into the two front hottest rooms in the house.

History:

In Tulsa OK — hot summers and a lot of humidity, cats and a dog in the house. Two people one working from home permanently.

Allergy problems of residents – lots of pollen/dust in Tulsa and the cats aren’t helping but they are too cute to rehome.

Inherited home 1600 sq ft — with an AC that was oversized because they wanted to convert the garage.

Vents under the house were leaky and even had holes.

Had some of the under home (crawlspace) feeds replaced

Sealed off the vents to and from the garage and then added another return in the house (next to the original) and added two overhead feeds to the two front rooms — because the contractor said otherwise the pressures would be too much.

Have a great collection of air filters in most rooms of the house

Have a small dehumidifier which works great (integrated pump) set at 55% and the air is set to dehumidify if it gets above 65%.

Added ecobee thermostat and sensors.

After the above — average bill dropped from $130 to around $100 even with added load of working from home.

I’m currently wondering if there is some reasonable way to get a better balanced system. The front rooms are important during the day and the back bedroom at night but its a small home and not zoned.

I have a Clean Comfort AE14-1620-51 which turns out is damaged but bought “new” at a yard sale rather cheaply. The neighbor and I are deciding how to reasonably deal with him forgetting to manage the damage to a replaceable unit. All together the unit is going to be about $200 + install costs.

The AC is a Trane, oversized (or so I’m told — before my time) and at least 10 years old.

My questions devolve to the following:

1. Clean Comfort air filter (yes/no) — or another brand?

2. Whole home dehumidifier? (yes/no) — SantaFe and which one?

3. There are times when the outside air is cooler than inside due to the Sun going down during the summer — opening windows is difficult to really vent and I’m wondering if we can get a system that will vent in using the AC ducts and just do it automatically.

4. AC replacement? I assume we are going to need to replace it. Should we go with a heat pump and a recommendation?

Financially, I want to tune the house for efficiency and comfort with as much “set and forget” as possible. Upfront costs are not a constraint as long as the return on investment pencils out.

Finally, not sure if it matters much but I’m getting solar for the roof, the solar will be more than our usage by design (EV in our future probably) and I happen to work for an installer. So, we are also looking to replace the gas water heater with an electric on-demand.

David,

Is there any reason why you wouldn’t be exploring the installation of inverter driven mini-split system(s)? It seems that you want to have additional stand-alone filtration in the home. The mini-split would benefit from this.

Mike

David,

Have you look into power requirement for the electrical on demand water heater? It could be in excess of 100amps to get a 50F rise on 4gpm. That could require some major electrical upgrades. We installed a Rheem HPWH and have been very happy with the capacity and energy usage.