Can You Save Money by Closing HVAC Vents in Unused Rooms?

Your air conditioner, heat pump, or furnace probably uses a lot of energy. Heating and cooling makes up about half of the total energy use in a typical house. For air conditioners and heat pumps using electricity generated in fossil-fuel fired power plants, the amount you use at home may be only a third of the total. A question I get asked frequently is whether or not it’s OK to close vents in unused rooms to save money. The answer may surprise you.

The photo above shows a typical vent for an ducted HVAC system (air conditioner, heat pump, or furnace). On the return side, you’ll typically see plain grilles, but on the supply side, where the conditioned air gets blown back into the house, most HVAC contractors install registers like the one above. It has a lever of some sort that allows you to adjust the louvers behind the grille.

You’d think that since it’s adjustable, it must be OK to open or close it to suit your needs, right?

The blower and the blown

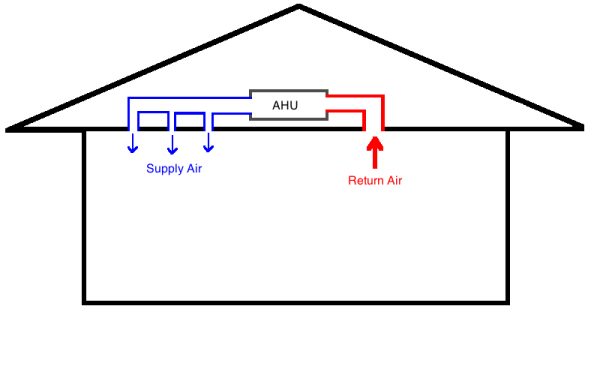

The blower in your HVAC system is the heart of the air distribution. It pulls air from the house through the return ducts and then pushes it back into the house through the supply ducts. In high-efficiency systems, the blower is powered by an electronically commutated motor (ECM), which can adjust its speed to varying conditions. The majority of blowers, however, are of the permanent split capacitor (PSC) type, which is not a variable speed motor.

In either case, the system is designed for the blower to push against some maximum pressure difference. That number is typically 0.5 inches of water column (iwc). If the filter gets too dirty or the supply ducts are too restrictive, the blower pushes against a higher pressure.

In the case of the ECM, a high pressure will cause the motor will ramp up in an attempt to maintain proper air flow. An ECM is much more efficient than a PSC motor under ideal conditions, but as it ramps up to work against higher pressure, you lose that efficiency. You still get the air flow (maybe), but it costs you more.

The PSC motor, on the other hand, will keep spinning but at lower speeds as the pressure goes up. Thus, higher pressure means less air flow, and, as we’ll see below, low air flow can cause some serious problems.

The important thing to remember here is that no matter which type of blower motor your HVAC system has, it’s not a good thing when it has to push against a higher pressure.

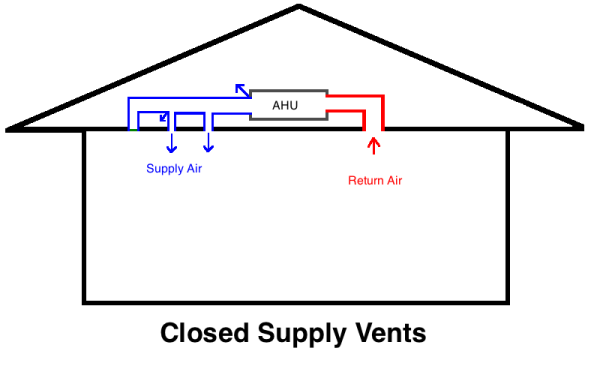

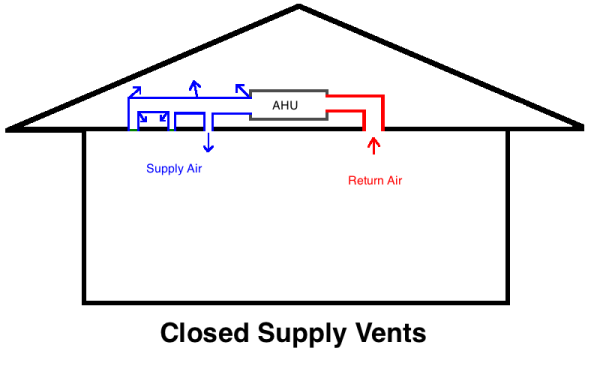

Closed vents increase pressure

In a well-designed system, the blower moves the air against a pressure that’s no greater than the maximum specified by the manufacturer (typically 0.5 iwc). The ideal system also has low duct leakage.

The typical system, however, is far from ideal. Although most systems are rated for 0.5 iwc, the National Comfort Institute, which has measured static pressure and air flow in a lot of systems, finds the typical system to be pushing against a static pressure of about 0.8 iwc. Now we’re ready to address the question of closing vents.

When you start closing vents in unused rooms, you make the duct system more restrictive. The pressure increases, and that means an ECM blower will ramp up to keep air flow up whereas a PSC blower will move less air. Most homes don’t have sealed ducts either, so the higher pressure in the duct system will mean more duct leakage, as shown below.

The more vents you close, the higher the pressure in the duct system goes. The ECM blower will use more and more energy as you do so. The PSC blower will work less but not move as much conditioned air. In both cases, the duct leakage will increase further.

What about heat?

In addition to moving air, your air conditioner, heat pump, or furnace is also cooling or heating that air that flows through the system. The air passes over a coil or heat exchanger and either gives up heat or picks up heat.

In a fixed-capacity system—and most are—the amount of heat the coil or heat exchanger is capable of absorbing or giving up is fixed. When the air flow goes down, less heat exchange happens with the air. As a result, the temperature of the coil or heat exchanger changes.

If air flow is low, it’ll dump less heat into the coil in summer, and the coil will get colder. If there’s water vapor in the air, the condensation on the coil may start freezing. You might even end up with a block of ice, as shown in the photo below. And ice on the coil is really bad for air flow.

It’s also bad for the compressor as not all of the refrigerant evaporates and liquid refrigerant makes its way back to the compressor. If you want to have to buy a new compressor, this is a good way to do it.

Same thing if you have low air flow over a heat pump coil in winter. You could get a really hot coil, high refrigerant pressure, and a blown compressor or refrigerant leaks.

Similarly, low air flow in a furnace can get the heat exchanger hot enough to cause cracks. Those cracks, then, allow exhaust gases to mix with your conditioned air. When that happens, your duct system can become a poison distribution system as it could be sending carbon monoxide into your home.

9 unintended consequences of closing vents

Let me now summarize the problems I’ve described above that can result from closing vents in your home. The first thing that happens is the air pressure in the duct system increases, which may give rise to these negative consequences:

- Increased duct leakage

- Lower air flow with PSC blowers

- Increased energy use with ECM blowers

- Comfort problems because of low air flow

- Frozen air conditioner coil

- Dead compressor

- Cracked heat exchanger, with the potential for getting carbon monoxide in your home

- Increased infiltration/exfiltration due to unbalanced leakage , as I described last week

- Condensation and mold growth in winter due to lower surface temperatures in rooms with closed vents

You’re not guaranteed to get all the problems that apply to your system, but why take the chance.

A Kickstarter project to avoid

I recently wrote about all the IT folks who are trying to follow in Nest’s footsteps and profit from the home energy efficiency movement. I used the Aros smart window air conditioner as the example of companies that think you can solve problems just by creating a product with a smartphone app.

Well, meet a more malignant idea: the E-vent. (You can find it easily enough by searching on the term “Kickstarter E-Vent.”) It’s just a Kickstarter project right now, and maybe it won’t get funded. If it does get funded, however, it will be subject to all the problems I described above. It doesn’t matter whether you close the vents by getting up on a ladder in your home or from the beach in Cozumel. It’s still a bad idea.

The E-Vent page on Kickstarter says they monitor the air temperature and open vents if the temperature gets too cold while air conditioning or too hot while heating. Of course, that’s not going to work unless they monitor the temperature right at the coil or heat exchanger. And that still probably wouldn’t work because there’s a wide range of acceptable temperatures for different systems.

This is an HVAC product developed by people who don’t know some very important principles of heating and air conditioning. Let’s hope they don’t kill anyone.

The only way closing vents could work

The fundamental problem here is that closing supply vents in your HVAC system changes what comes out in particular locations. It doesn’t change what the blower is trying to do. Nor does it change the amount of heat the air conditioner, heat pump, or furnace is trying to move or produce.

It’s possible you may be fine closing a vent or two in your home, but it will depend on how restrictive and leaky your duct system is. If it’s a typical duct system with 60% higher static pressure than the maximum specified, closing even one vent could send it over the edge. If it’s a well designed system with low static pressure and sealed ducts, you shouldn’t have a problem as long as you don’t try to close too many.

The only way something like this could work is if closing a vent signaled the blower to move less air and the air conditioner, heat pump, or furnace to move or produce less heat. (Properly designed zoned duct systems do this by using variable speed ECM blowers with multi-stage systems.) Otherwise you’re subject to those 7 unintended consequences, one of them potentially deadly.

Related Articles

The Sucking and the Blowing — A Lesson in Duct Leakage

What Is Pressure? – Understanding Air Leakage

4 Ways a Bad Duct System Can Lead to Poor Indoor Air Quality

Thanks to Curt Kinder, David Butler, John Semmelhack, Eric Sandeen, and Dale Sherman for suggestions in the comments below that made this article better and more complete.

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 90 Comments

Comments are closed.

The earth is NOT flat!

The earth is NOT flat! Blindly believing in “makes sense” common sense is flat earth thinking.

Great post Allison!

We close lots of vents,

We close lots of vents, automatically, many times per day…in our zoned heat pump HVAC systems.

Of course we always use multi stage systems with ECM blowers and design ductwork and system to accommodate system minimum airflow

Oh yeah, no return bypass dampers allowed, either. It is too easy for those to cause iced coils and blown compressors.

Curt K.:

Curt K.: Thanks for mentioning zoned systems. What you describe meets the requirements I stated at the end of the article. When you close off vents — or whole duct runs, as in a zoned system — your zoned system also changes the amount of air flow and heating or cooling capacity.

Awesome! An HVAC guy

Awesome! An HVAC guy yesterday was just talking about how closing vents saves energy, and I was caught a bit flat footed on the reasons that’s a bad idea, thanks for the great explanation!

As far as comfort goes, lower/higher surface temps in those rooms could lead to mean radiant problems in adjacent rooms, correct?

Nate – ask the HVAC guy to

Nate – ask the HVAC guy to PROVE that closing vents saves energy…by “prove” I mean gather all relevant data with vents closed vs open. A home with oversized ducts and properly sized equipment MIGHT save a few percent by closing vents to 1-2 unused rooms, but when is the last time you came across oversized ductwork?

Bill – Possibly the best zoning system available for homes is Carrier’s Infinity system. Its dampers are true modulating and it best manages excess air when just a small zone is calling.

If the wallet isn’t fat enough for Infinity, there are ways to compensate for minimum system airflow using off-the-shelf zoning gear.

Any HVAC contractor whose zoning approach incorporates a return bypass should be sent packing.

All of Allison’s writing about further restricting likely-already-crappy ductwork are spot on.

The Kickstarter people are in dire need of adult supervision and oughtn’t be left alone with sharp tools or live circuits exceeding 9 Volts.

So what should be done about

So what should be done about people/rooms that have different needs after a system is installed? For example, in our home the wife has an office that is too cold for her, and I have one that is too hot. We would trade but her office is larger and she needs the space. The rest of the house is comfortable overall, but these two rooms remain a problem. I can tolerate being overly hot, however she has trouble with being so cold. If I turn the thermostat up, the whole home becomes too warm and my office becomes unbearable. The only solution I can come up with would be a minisplit in my office and that wont be happening since we just replaced the AC last year.

Great article, Allison.

Great article, Allison. However, there are even more drawbacks to closing HVAC vents that need mentioning. If the supply duct in a closed room is closed off, the return duct creates a negative pressure in that room. This causes unconditioned air to be drawn through interstitial leaks from outside. The main body of the house pressure will increase slightly. One can see evidence of this by monitoring the change in house pressure when a closed room supply duct (or return duct) is closed.

If the closed off room with a closed supply duct has an air pathway to the CAZ, the CAZ pressure will be lowered. I have seen CAZ pressures up to -15 Pa. in this scenario. In one house, the second floor bedroom (with closed door) with a closed supply duct depressurized the basement CAZ to -11 Pa.

One needs to be aware of the whole house implications of closing HVAC registers, not just the implications to the HVAC system.

I wish I read this before my

I wish I read this before my compressor blew last year and cost me $2k for a new one. When they built our townhome, they put a duct under our dishwasher that they they had to cover up, so we’re already working with a permanently covered vent. Then I have other areas where I have reduced airflow (vent right behind a door)…so last year my compressor blew and I believe it’s because the problem you describe above where it froze up.

Great article and I have

Great article and I have preached this for years to leave all the supplies and returns open all the time in every room. But this year I have found myself closing some vents on first floor to force colder air to the second floor. Don’t like doing this but only thing I could do to cool off my second floor. I have done all the air sealing and have R50 in Attic. I run into to these folk who say they balance your system so what say you.

As an aside, I just did a static pressure test to discover I have 1.1 total and my system says I should be at .5. I live in a tract home built 13 years ago with a 130,000 Btu system and I am confident it is almost double over sized but not able to replace it yet.

How about all the stories I

How about all the stories I’ve heard about people draping blankets, sheets or draperies at the top of stairs (in multi-floor homes) to cut down the flow of warm air to unused upper rooms in Winter or decrease drafts year round? It’s amazing what people can come up with that “they are convinced” help them cope with building science issues.

Allison,

Allison,

Thanks for your thoughtful analysis. I absolutely agree with your conclusions regarding increased duct leakage (assuming the ducts are not properly sealed).

I have one question however; you stated “Less air flow means the blower works less hard. Less work means less instantaneous energy use, but since it’ll probably run longer, any savings there are unlikely to materialize.”

Why would the blower run longer, unless of course the thermostat is in the room with a closed vent? If the system is trying to satisfy the thermostat’s setting, and air flow is not restricted to the area where the thermostat is located, wouldn’t the system run about the same amount of time? I suspect in some cases the system’s cycle might be shorter, if increased pressures in the duct work increased the flow of conditioned air to the location of the thermostat. Obviously, all sorts of comfort issues might be introduced as well as air flows vary from the original design. This also assumes that the ductwork system was “designed.”

Richard – if ducts are

Richard – if ducts are accessible such as via attic, it is usual a simple matter to add manual balancing dampers.

Dale – I’m glad I rarely deal with CAZs

Chris – the failure mode for frozen coils and blown compressors is that the TXV (refrgerant metering device) pinches down in response to low airflow across frozen coil. Compressor windings and bearings are cooled by proper flow of return refrigerant gas. Ideally the compressor is saved by a low pressure cutout, but sometimes those are left out in a race for the lowest possible price for code minimum systems.

I hope you got some warranty relief!

Great post Allison!

Great post Allison!

As an energy auditor this topic comes up often, as always your explanation is right on and clear

Running with extremly high

Running with extremly high statics on an ECM motor is also a great way of shorting its module’s life.

thanks…now I can just refer

thanks…now I can just refer people to this article & save myself time from repeating the same thing over and over.

simple answer is no

simple answer is no

as we experience wall and ceiling (and floor) temperatures via long radiation, our comfort is based on just this. by having rooms and exterior around us that are either too hot or cold defeats the purpose. Particularly with ducted system. Insulation is the only key, and twice the code.

Allison, How very odd that

Allison, How very odd that your illustration shows ductwork in the attic, considering the campaign currently being waged by energy and green building experts (including you, I presume) to get ductwork out of these unconditioned spaces.

As several have noted, it’s

As several have noted, it’s sometimes desirable to modulate the amount of air going to different rooms, to account for difference in loads from winter to summer, especially in single zone multi-floor homes. The answer of course is that it’s certainly possible to design a system that accomplishes this, but the key word here is “DESIGN”… it must be designed that way. When a homeowner starts closing multiple registers on a system that’s already has restricted airflow (pretty much the norm), the at best, it’s going to impact system performance and efficiency, and at worst, well, all of the above.

@Armand, the reason the blower might run longer is that the higher pressure will cause a PSC motor to slow down. This will reduce system capacity, so a cooling or heating call will take longer to satisfy. And since lower airflow will reduce the sensible efficiency of an A/C, it will increase operating costs.

There’s also another company

There’s also another company trying to push a so-called Smart Vent:

http://www.keenhome.io/

They seem to be getting a lot of press – I ran across them because Builder Magazine featured their product.

An important concern not yet

An important concern not yet mentioned (and this is true of zoned systems as well) is that if you shut off the heat in an unused room, it can create conditions for mold growth and condensation on windows, depending on interior moisture levels. The risk is obviously going to be greater in a tight home, since it naturally has higher winter RH levels.

The reason to install a zone control system is to achieve better airflow balance as the relative loads in different parts of the house change from winter to summer, day to night, and upstairs to downstairs, not to shut of the air to unused rooms.

Unfortunately, many mechanical contractors don’t convey this message to their customers.

If at any time the

If at any time the cool air drops below a minimum temperature or the warm air goes above a maximum temperature, the E-Vent overrides its settings and opens up, protecting your Heating and A/C system.

Um…. if the vent is closed, and no air is flowing through it from the HVAC system, how exactly would this temp change take place?

Eric wrote: “…if the

Eric wrote: “…if the vent is closed, and no air is flowing through it from the HVAC system, how exactly would this temp change take place?”

Good catch. I didn’t see that on the E-Vent website but it gets worse. In order to “protect” the HVAC system, the vent would have to monitor the temperature directly at the output of the heat exchanger or DX coil, and even then, the acceptable range (let alone the efficient range) will vary depending on the particular system’s design.

Good article, Allison!&

Good article, Allison!

A small pet peeve, though – you wrote: “The PSC motor, on the other hand, will keep spinning merrily along at the same speed.” The PSC blower speed (RPM) under higher static pressure will actually drop, and along with it, the airflow as well.

Dale S.:

Dale S.: Dang! That was supposed to be in this article. I even wrote up a whole article about that topic the week before this one as a lead-in to this topic. I’ve expanded the list of unintended consequences to include that. Thanks!

Armand M.: I’ve revised that part of the article because it wasn’t clear and because I was wrong about one part of it, as John Semmelhack pointed out in his comment.

Janell: Yes, I’m campaigning to get ductwork out of unconditioned attics, but I’m also not fighting against reality. Sadly, there are many, many systems in attics.

Eric C.: Oh, no! That’s horrible. Even worse, some of their grilles look much more restrictive than the ones they’d be replacing so even when they’re open they’re making things worse.

David B.: Thanks for bringing up the mold and condensation issue. I’ve added that to the list.

Eric S.: Like David, I also missed that on their website. My first thought was the same as his, too. If they’re not measuring at the coil or heat exchanger, they’re not protecting the system.

John S.: Oops! It’s fixed now. Thanks!

One thing to note. When a PSC

One thing to note. When a PSC motor driven fan experiences increased static pressure it flows less CFM and its watt draw drops.

What if the system is

What if the system is checking the static pressure across all of the vents?

What about if it tracked the on time of the system and minimized that, couldn’t it possibly account for duct work loss.

I think they would have better luck operating them thinking of it as dynamic balancing instead of a weird aftermarket zoning system.

@Dwayne, measuring static at

@Dwayne, measuring static at the grille isn’t helpful since there’s virtually no static to measure at an open grille. The only static that matters is total static, which must be measured on either end of the air handler.

Your second comment also makes no sense. System run time varies depending on current load and other factors that have nothing to do with duct system pressure.

As for your third comment, I’m not sure how your concept of ‘dynamic balancing’ is any different that what a zoned air distribution system is designed to do in the first place.

@David

@David

Regarding your first comment. My thought is that you might be able to measure the total pressure at each register with all of them wide open. Then a relative adjustment should register at all of the end points (if there wasn’t additional pressure at the registers, then there wouldn’t be more at the back end). I have to assume you believe in Newtonian physics?

I don’t think you understood the second comment and I certainly should have explained it better. It seems like many say closing registers -> increased pressure -> potentially increased duct leakage – which makes a lot of sense. My comment was that with a smart system, it should be able to learn whether closing registers is causing additional leakage or any other inefficiency (well maybe not increased current on the blower if its an older unit) by observing the total time the system is on. Assuming a fixed temperature and consistent weather, it seems like by simply observing the on time of the system one day, and then changing the registers and observing the next day, an intelligent system could learn how to minimize on time.

Dynamic balancing is more fine grained. If the east facing bedroom is warmer in the morning, old school HVAC cant handle it without it being too cold later in the day. These devices seem like they are trying to eek out energy and solve some building science problems that traditional HVAC has ignored. I don’t expect traditional HVAC contractors will embrace something new, because 1) they have seen what can and very well might go wrong and 2) they are somewhat set in their ways and will reject a higher tech solution that didn’t exist when they were training. It might mean that these systems are limited to newer construction where newer blowers, compresses and furnaces can handle more dynamic loads. It could allow for a time domain multiplexed system where a smaller central unit can handle a larger space, say based on occupancy.

These systems could be totally problematic and not do as promised. They could alternatively be the next version of HVAC. I certainly don’t know.

Dwayne wrote: "

Dwayne wrote: “I have to assume you believe in Newtonian physics?”

Are you serious? Please don’t patronize me about physics when you apparently don’t even understand basic duct system pressure concepts. I mean that with no disrespect.

Measuring “total pressure at each register” doesn’t get you anywhere. By “total pressure”, did you actually mean total static pressure? Here are some basic concepts that may help…

* for any given point in a duct system, total pressure = static pressure + velocity pressure

* blower output (the main concern here) is a function of total external static pressure

* total external static pressure is NOT the sum of the end-point static pressures

* total external static pressure can only be measured at the blower (return side + supply side)

The static behind the grille only represents tiny resistance of the grille itself, not the resistance of the upstream components. Also, you can’t add static pressures for what are essentially parallel paths (think parallel versus series resistance networks in electronics). Bottom line, the sum of static pressures taken anywhere in the branches has no correlation to the total external static that that blower sees, which is what’s at stake here.

You could (theoretically) measure and sum the velocity pressures at the ends, but getting a representative sample is a lot more involved than you might imagine, and that still doesn’t correlate to blower output, at least not without the cross-sectional area of every measurement point Good luck with that.

“It seems like many say closing registers -> increased pressure -> potentially increased duct leakage – which makes a lot of sense. “

Perhaps. But duct leakage isn’t the side effect we’re concerned about, It’s all about airflow across the refrigeration coil or heat exchanger. In any case, the solution to duct leakage is to seal the ducts.

“Dynamic balancing is more fine grained. If the east facing bedroom is warmer in the morning, old school HVAC can’t handle it…”

Dynamic balancing is what any properly designed zone control system is supposed to accomplish. In fact, this should be the primary objective. In particular, zones should be organized based on similarity of load dynamics, and only secondarily on how the rooms are used. Not many contractors understand that. I would argue that the “old school” folks were much better than most of today’s crop who purchase a software tool and think that makes them an expert.

Bottom line: what’s missing from zoning is not product innovation but application design skills. Smarter products will not change that, especially if the folks conceiving the products don’t even understand the fundamentals, which seems to be the status quo with today’s connected-everything world of phone apps.

@Dima, if you added a couple

@Dima, if you added a couple of vents, then closing a couple of others is probably fine.

Unfortunately, very few residential HVAC installers test the static pressure of the duct system, or balance the airflow (perhaps because builders don’t know to include these basic tests on their specifications). I recommend having a qualified technician (National Comfort Institute or NATE) perform static testing and air balancing on all homes with forced air heating and/or cooling. That way your system isn’t based on guesswork.

@Jim, sounds like your ducts

@Jim, sounds like your ducts are flex with the black plastic outer liner. It serves as a vapor retarder to prevent moist air from condensing on the inner liner during cooling operation, and (2) as an air barrier to prevent air from permeating the insulation layer, which can seriously degrade the effective R-value.

In order to function properly, the vapor retarder (plastic or foil outer liner) must be continuous and carefully sealed at all seams.

If ducts are located outside of conditioned space (vented attic, crawl space or unconditioned basement), you need to get this repaired. A local contractor would need to look at the ducts to see whether it makes sense to try to re-wrap or replace the ducts. It’s usually better to replace, but that will depend somewhat on ease-of-access.

I turn off the vents and I

I turn off the vents and I block the return air flow also , so according to what I am reading here , this isn’t the best way to save .

Joe. It isn’t the BEST way to

Joe. It isn’t the BEST way to save, but what is the best way depends on your house, your heating and cooling system, and our climate.

Shutting off vents is most detrimental to the operating efficiency of air conditioners and heat pumps. It is detrimental, but less so for furnaces. In all three cases, it increases the probability of premature failure of the unit. Not knowing your situation it is hard to say what is best, but here is a list of good items that may be applicable:

Ceiling insulation, duct sealing, duct insulation, Air sealing at the plane between the attic and inside, wall insulation.

Boy, I’m glad I found this

Boy, I’m glad I found this site. For my situation, however, it raises even more questions than it answers.

I just bought a one-story house in northern Iowa, and we’re facing our fist winter here (brrr!!!). The house was built in the 1920s, and was added onto in the 80s. The original portion of the house (~950 sq ft) has service and return ducts that seem really poorly situated. The home energy auditor even pointed this out. Basically, the service vents are located so close to the returns that the air only heats a few corners of the main living area.

The main issue though, which brought me to this site, is my cold bedrooms. Okay, so picture this… There are five main duct lines that emerge from my gas furnace blower: 2 to the addition, 1 to the living room nearby, 1 to the humidifier, and 1 to what I call a “main line” with several additional branches. Anyway, the bedroom heaters have always seemed to pale in comparison to the living room heaters. Turns out, the living room heaters are all further up the “main line”, and the bedrooms are the last of several vents along just 1 of 5 service lines altogether.

This morning, I thought to myself, I’ve had enough, and I closed all the dampers to the living room service ducts – thinking that, since they’re poorly situated as it is, it would almost be a waste not to close them. Also, consider the two service lines going to the addition (which I left open) were added in the 80s perhaps spreading the heat too thin. It felt like that anyway, because by the time the hot air got to the bedrooms, it was weak and barely warm.

So, my question: Would closing, or at least dampening a few of the poorly situated service lines be all that bad? Might doing so offset the extra service ducts added when the addition was built?

Closing some of the service vents certainly achieved the goal of sending warmer (and stronger) air to the bedroom vent I left open. It was nice to actually hear the air coming in. But I obviously don’t want to damage the furnace. So, follow-up question, is there anyway for the average homeowner like me to test the pressure in the vents to get the perfect balance between sending the air where I want while maintaining safe pressure?

It would be nice to just leave everything wide open like this article suggests, but as it is now, my heating system is very poorly situated and unbalanced. Thanks in advance for any help!

@Codie, essentially, you

@Codie, essentially, you rebalanced your furnace’s airflow by trial-and-error. There are some potential downsides to doing this yourself.

As noted in the article, closing vents reduces the total system airflow, which causes the supply air temperature to rise in heat mode, and to drop in cooling mode.

Furnaces have a wide operating range, so closing a small percentage of outlets isn’t likely to cause a problem, especially since vents had been added to service the addition.

In cooling mode, a reduction in airflow can affect on performance. If you have central A/C, you’d like to know if your efforts materially changed the evaporator’s performance. At a minimum, you’d need to check external static at your furnace and compare that with the blower table to estimate system airflow. Learning how to do this properly and to assess the results isn’t trivial.

Also keep in mind that if your bedrooms don’t have individual returns or transfer grilles (or a large enough door undercut), it may be impossible to get enough air to those rooms with doors shut, at least not without causing an outsized effect on the system and the rest of the house. And without adequate return paths, you’ll end up with too much air in those bedrooms when the doors are open, and not enough air in other rooms. So the first step in any air balancing job is to make sure there’s an adequate return path to each room. The standard is to have less than 3 Pascals pressure difference across closed doors with HVAC blower running. This ensures that opening and closing doors will not materially affect air balance.

@ Codie: What a Pickle.

@ Codie: What a Pickle. Whoever did the add on apparently messed up the balance of the system that may have been present before. Hard to say.

There are two ways for a regular person to determine whether the total airflow through a furnace is sufficient.

Method 1) Measure the temperature of the air entering the return grille

Then measure the temperature of the air existing the supply grille nearest the furnace. The difference in temperature is the heat rise.

Then look on the specifications plate inside the furnace (is should be inside the front panel. If your heat rise is within the range specified by the manufacturer, you will be OK.

Method 2) Turn up the thermostat as high as it goes. Then go watch the furnace. If the burn is not continuous (cycling on the limit switch) Then you definitely have trouble — mostly durability issues.

While there are many experts that advocate for a return in every room, or some specific return pathway. I am not in that group. In the Southwest people get by all the time with a single return in the house.

It may not be ideal, but it works.

What you are doing by closing off registers is the same thing a professional balance company would do, except they would do it at a damper right by the where the run to the room takes off the furnace plenum or main trunk line.

I hope all these terms are not too confusing.

In the end, you want to be comfortable in your home, bedrooms included. If you can check the heat rise of the furnace, then doing some DIY balancing is understandable, if not ideal.

With respect to the close proximity between the return and the supply registers. This should not be a problem if the velocity leaving the supply register is high enough (throwing the air across the room).

Good luck and save up some money to have a good performance contractor come put in a good system (ducts, terminals (aka registers) and furnace) when you are ready.

Great article, but it made me

Great article, but it made me think about something with an issue I’m having.

My house has 3 air registers in the basement, 9 on my main level and 7 on my upper level. People who have similar setups and also open all their vents usually have to deal with their basement being colder than the rest of the house all year round and the upper level usually being hotter that the rest of the house all year round. What’s the usual remedy? Close off the 3 basement vents in the summer time while leaving the rest of the vents in the house wide open and also closing off some of the vents on the upper level while leaving the other vents open in the rest of the house during winter time.

I’m not sure if this would work, but what if I set my vents on my main floor to a half open position all year round and then partially open my basement vents in the summer time while FULLY opening my upstairs vents? In the winter time, I could partially open my upstairs vents while FULLY opening my basement vents.

Does this sound like something that may work? It seems like it could because none of my vents would ever be fully closed at all. I also never have issues with my main floor ever being too hot or too cold. I should also point out that 2 of my upstairs bedrooms have no return air vents.

@Sean, fixed-volume duct

@Sean, fixed-volume duct systems are, by definition, a compromise even in single floor homes since solar gains significantly change the load balance from morning to afternoon, day to night, and winter to summer. These impacts can be minimized with good duct design, window selection and shading.

However, it’s unreasonable to expect a single fixed-volume heating/cooling system to maintain consistent temperatures across multiple floors, especially winter to summer. Each floor needs to be set up as a separate zone with its own t’stat, either with one system per floor or automatic zone control (or a combination). Some states now require multi-floor homes to be zoned.

Seasonal air balancing as you propose can accomplish similar results. But doing this yourself has downsides (see my above response to Codie).

Maintaining adequate airflow in cooling mode is especially important, which is why I advise against DIY air balancing. A professional air balancing technician, aside from balancing branch ducts within each floor, can install manual balancing dampers in the upstairs & basement trunks, with marks or limits to assure the right amount of adjustment each season. Of course, this assumes those trunks are accessible.

The main point is the importance of verifying system airflow when doing this sort of balancing, since this creates additional back pressure on the blower.

More often than not, system airflow is already too low, even with vents fully open, due to undersized or poorly installed ducts and/or overly restrictive filters. In this case, the duct system must be modified, typically by adding one or more returns or supplies, increasing filter surface area, or all of the above. Sometimes it’s just a matter of increasing the blower speed. A qualified technician can quickly sort this out with simple diagnostic tests.

Question specific to heating

Question specific to heating mode: Can an a add-on system accomplish “balancing” by monitoring the variables at the motor/furnace while adjusting air flow to individual rooms using room vents with boost fans and opening/closing vents? Controlled by room thermostats? Can thermostats in every room can be set which gathers individual room temps and turns on/off room vent boost fans while opening/closing other vents as required while measuring the system vitals at the blower/motor/furnace. In other words, electronics monitor the system vitals and adjust the vent openings and boost fans. Is that possible?

@R.Poulin, what you describe

@R.Poulin, what you describe is essentially an intelligent zone control system. Systems that do most of these things already exist, but they require professional installation. Even the smartest system doesn’t eliminate the need for an installer who knows what s/he’s doing.

BTW, modulating airflow to rooms by partially or fully closing the vents isn’t the best strategy for a couple of reasons. First, air that bypasses a partially closed vent can create a lot of unwanted noise. Balancing dampers are typically installed at the beginning of supply branches or trunks, so any airflow noise is removed from the room. Second, motorized vents cost more than motorized in-line dampers (and much more than manual balancing dampers). Moreover, you’d need one for every supply outlet. Keep in mind that larger rooms often have more than one vent. Also, when designing a zone control system, rooms are typically grouped into fewer zones. So by placing dampers further upstream, you only need a fraction of the dampers, as well as fewer thermostats.

Zone control is least expensive and works best when installed at the time the home is being built and the duct system specifically designed for zoning. But wireless technology is making zoning more accessible for existing homes, although you’re pretty much limited by whatever duct topology you inherit.

So perhaps the best “add

So perhaps the best “add-on” (retrofit) system for room-by-room individual heat control/comfort would be small elec. boost heating vents which replace the hot air vents in the rooms you desire more heat? Remove the existing room hot air vents/grills in the rooms you spend more time in, and replace them with vents/grills which have built-in heating elements. Of course, they would need to plug in to a elec. receptacle to power the heater, but they would be almost unseen as they would be inserted into the vent. They could be designed to operate when the air flow is blowing only (the system is already running). They would “boost” the air temp in the rooms needed right at the point of air entrance and be “out of sight”. Would not be surprised if someone already makes something similar.

Someone just posted this on

Someone just posted this on Facebook, and I had to refute every one of the claims in this article. So, for sake of sanity, I’m sharing that here.

No! In fact, one of the premises of the article is that higher pressure makes the fan work harder – the exact opposite is true. When you use your hand to plug a vacuum hose, does the motor spin faster? Of course. That’s because the motor has *LESS* working against it in the vacuum – less moving air means the impeller free-wheels against a vacuum. Same applies to pressure on a fan blade – less moving air, less force being applied to the motor, so the motor speeds up by the nature of its operation (speed is a factor of the work being done).

Leakage is a minor concern, but duct work isn’t just slipped into place and left there like it won’t go anywhere. Leaks mean the duct isn’t even attached to the outlets, which is a very BAD thing for more reasons then just this. Most ducts I’ve seen are sealed to the outlets with some pretty secure tape, and that means no leaks are possible of any worthwhile consequence (we’re talking a whisper of air versus a whirl of air). If it’s leaking anyway, you can only make it very marginally worse by blocking it.

And… the benefits you gain by blocking a vent mean you’re no longer heating the unused material in that room – the walls, floor, ceiling, all stay the same room temperature, and conduct heat through them to the outside. So if the unused room’s vents are closed, and you walk in and feel it cold, that cold (or hot, if you’re using A/C!) feeling is all the energy you saved by not keeping a large temperature differential between that room’s materials and the outside world.

The air circulation exchange argument (I didn’t see it, but it’s another common myth) is also bogus – in fact, blocking an unused vent in a closed room is a GOOD thing there, since air usually escapes under a tiny crack under the door, creating outward pressure on the room for air to escape through outlets and other holes to the outside world. With a blocked vent, you’re creating less pressure in that room that would need to escape under that door crack (or through the outlets!) and most would go back under the largest “in-loop” space – under the door – instead of escaping.

I hate having to write these things, but more than that, I hate when authentic “energy” websites spread energy misinformation like this. 🙁

Matt F.:

Matt F.: If your knowledge of building science and mechanical systems matched your indignation, your comment might be more convincing. Apparently you’ve got some fixed ideas stuck in your head because you don’t even seem to know what I wrote. You might want to check what I wrote about PSC vs. ECM blowers before you tell me about blowers working less hard. You might also want to find out how bad duct leakage really is. It’s far from a “minor concern” in most homes.

And then to close by refuting something you didn’t even see in the article proves that you’re operating from some imagined position that doesn’t apply here.

Really, Matt? Is that the best you can do?

The problem with this article

The problem with this article and comment thread is that virtually all of the ‘evidence’ is anecdotal. ‘I have seen frozen evaporators and closed dampers’ – and have you ever just seen closed dampers or frozen evaporators by themselves – of course…

The reality is that virtually every vent installed in a home has adjustable louvres yet putting a motor on them and informing that with sensor data makes old school HVAC pros uncomfortable. The reality is that saving energy is only one facet of this whole question. The HVAC crowd of yesteryear is convinced that the systems are adequate as is, but talk to many people and they will tell you that rooms heat/cool unevenly due to floors (higher floors get too much heat and winter and not enough AC in summer), sunlight, or other dynamic conditions. Whether it saves money aside, and whether the built environment is compatible with dynamic loads and increased static pressure aside, the reality is that the HVAC industry, particularly the residential side, is in for massive change as cheap sensors and software companies start to eye the space. The traditional HVAC contractor is going to get left in the dust, dragged in kicking and screaming the whole way, or cautiously embrace perhaps. Customers are dictating smarter, more comfortable, more efficient systems and the old guard of the HVAC world has been failing for quite some time.

Joe M.: Oh

Joe M.: Oh, where do I start? You clearly don’t understand what this blog is all about or my relation to the HVAC industry. You wrote, “The HVAC crowd of yesteryear is convinced that the systems are adequate as is…,” implying, I think, that I’m part of that yesteryear crowd. Perhaps you should check out some other articles here before you speculate wildly.

Second, products that affect only what happens at the outlets of a duct system can never have the widespread positive benefits you envision. Yes, they may help a house here or there, but they will also cause a lot of problems and those “software companies” you refer to are going to be “failing for quite some time” into the future if they ever grab any kind of a foothold.

David Butler said it best in one of his comments above:

“Bottom line: what’s missing from zoning is not product innovation but application design skills. Smarter products will not change that, especially if the folks conceiving the products don’t even understand the fundamentals, which seems to be the status quo with today’s connected-everything world of phone apps.”

‘Where do I start’:

‘Where do I start’:

You could start by addressing more of my comment – all of your ‘evidence’ is anecdotal fear mongering.

Or feel free to explain why most registers contain articulated louvres, today. Its more convenient to quote some guy who categorical writes off any future enhancement to this ‘perfect’ system.

“Old school” HVAC

“Old school” HVAC guys vs. “new school” HVAC guys = red herring.

Truth is, some of us “old school” HVAC guys have a functional understanding of physics as pertaining to our trade. The addition of smart phone enabled apps and powered damper actuators on residential supply air registers changes none of that.

Any time total volume of a fluid flowing over a heat exchanger is reduced, the total amount of heat exchanged between the HX and fluid is likewise reduced.

Closing off dampers in supply registers will accomplish this very thing. BUT! Some might say…won’t the air in contact with the heat exchanger actually contain more heat or give up more heat due to the increased dwell time (reduced mass flow rate) with the exchanger? In the case of a DX evaporator for an a/c system in cooling/dehumidifying mode, it is true the air passing through the coil will become colder than it would under a higher mass flow rate. However, the temperature difference between the air and the boiling refrigerant is also less, hence an overall reduction in heat transfer between air and coil. It is a net loss of system operating capacity.

Therefore, if closing off dampers in unused rooms resulted in nothing more than a reduction of system capacity as outlined above, the only heartburn would be just that. However, with cooling coils condensing moisture and hermetic compressors that require a safety margin of suction gas superheat to prevent compressor destruction, reducing mass air flow over the indoor coil via closing off supply register dampers is antithesis to all of that.

Some of us may be “old school” but that does not equivocate to “knuckle dragger” or “luddite”.

Joe wrote: “Its more

Joe wrote: “Its more convenient to quote some guy who categorical writes off any future enhancement to this ‘perfect’ system.”

Wow. Anyone who’s read more than one of my comments in this blog over the years knows I would never consider the status quo ‘perfect’… far from it. The status quo in residential HVAC (perhaps what you refer to as old school) is pretty darn awful. But it’s not for lack of innovation. It’s because improvements that are both useful and practicable are really hard to come by.

But one thing is certain… you can’t innovate without first understanding the fundamentals – refrigeration 101 and air distribution 101. Then we can talk.

@Matt, you seem to be a bit

@Matt, you seem to be a bit confused about blower motors and pressure. An ECM (constant torque or constant velocity motor) will speed up when back pressure is increased. This is an energy hit, but there’s a limit, after which the motor will begin to stall. On the other hand, a PSC motor will consume less energy when back pressure is increased (as you assert), but it’s because it slows down. It does NOT speed up. But here’s the problem… when back pressure is increased, the motor moves less air (as you acknowledge), and therein lies the problem. Less air across the heat exchanger and/or evaporator coil can spell trouble, depending on whether airflow was already low to begin with. The point is that it’s a bad idea to do anything that effects system airflow unless you’re trained to measure and evaluate the impact of those changes. So any DIY product that affects duct system pressure needs to be called out for what it is.

Your assertion that leakage is a minor concern couldn’t be further from the truth. Just because you imagine it’s not an issue doesn’t make it so. There are plenty of field studies that quantify the impacts. Just google FSEC and duct leakage for example. It’s one of the top sources of energy waste in the home.

You’re correct that shutting off heat to a room can save energy. The point of the article is that a DIY zoning system is a bad way to achieve that. Also, in newer, tightly built homes, indoor humidity may be high enough (in winter) to create mildew/mold issue in rooms that are allowed to cool down too much (or worse, inside the walls of those rooms). Vapor pressure tends to equalize absolute humidity levels throughout a house, even under closed doors.

By the way, relying on the crack under a door as the return path for supply air is poor design practice (although very common). As a general guideline, a door undercut can only relieve about 2 CFM per square inch. More than that will tend to starve the room of supply air. Good design practice is to have dedicated returns in rooms where the door crack isn’t enough to relieve the design supply airflow. Better design practice is to use a jump duct or transfer grille.

I have to start out by saying

I have to start out by saying I love you articles.

I Have spent my early career installing multiple zone systems as they were getting laid out in the HVAC in the early 90’s . I was taking classes at the main distributors and thought I had a good grip on my product. Boy, I was wrong. We have spent the early part of 2000 replacing furnaces because these zone systems did not perform as we were told. Bypass dampers were killing the secondary heat ex-changers along with blowing up the house with incorrect room pressures. I would think very hard about installing a zone system in any project. Rick Chitwood has a correct way of installing a zone system by designing for full operation per zone. Still I believe it is super hard to do it correctly.

This new type of zone system would logically seem brilliant but it is actually disastrous. I guess this is more repair work for the HP industry as if we do not have enough to fix.

Great article Allison!!

It’s kind of funny that folks

It’s kind of funny that folks take the design of ductwork in their attic for granted. Do you think these major conglomerate behemoth A/C-heating corporations that install systems and ductwork for tens of thousands of new cookie-cutter subdivisions give a rats @#$ about how they lay their duct-work and choose the design of d-boxes and vents? They just throw crap up in the attic and if air comes out, it works. They lay so much excess flex in the attic that it looks like a giant spaghetti factory. Just bill the waste of duct to the housebuilder who in turn passes that cost onto the housebuyer.

In theory if you could close

In theory if you could close the return air by the samer proportion that you closed the vents, wouldnt this offer equilibrium to the system? So in theory if you closed 50% of the vents and closed the return air capacity by 50% this would this still cause the problems you describe? Would you still need a variable ECM?

Rich: Yes,

Rich: Yes, it could still cause problems because you’d be reducing the total air flow. That could crack the heat exchanger in a furnace, make the AC’s evaporator coil too cold, and burn out the compressor.

@Rich Allison is totally

@Rich Allison is totally right. Think of the whole duct system from the return grille to the supply grille as a long tube. The more you squeeze down the tube, the less air will flow. It doesn’t matter where in the tube you squeeze it down — before or after the fan.

Also a BPM (ECM) motor can be controlled to attempt to maintain a specific airflow. However it does so at the cost of more energy use and can only due so up to its limit.

One place that restrictions are taking place that most people do not think about is inside “the box”. The air handler (furnace, heat pump, AC) has internal resistance to airflow that needs to be addressed in new high performance designs.

I read the whole post, very

I read the whole post, very informative.

1) How does using $2 filters versus $25 allergy filters affect air flow. Some of these are made by a HVAC company, so did they design them with airflow in mind?.

2) If a bedroom does not have a return but you only close the door at night, will mold problems still be an issue?

3) Please explain more about this recent statement: ‘Vapor pressure tends to equalize absolute humidity levels throughout a house, even under closed doors’.

4) What is the ideal humidity level. I always thought humidity was a problem on warm sticky days, never considered it could be a problem on cool winter ones. Use a dehumidifier in winter?

@Robert, you sure do ask a

@Robert, you sure do ask a lot of questions! But good ones…

1) Those $2 fiberglass filters (sometimes called ‘bird catchers’ in the trade) are naturally less restrictive than pleated media filters. That said, there’s lots of variation among media filters with a given MERV rating, so it pays to check airflow performance curves. However, that data is hard to come by for popular consumer brands. And most residential contractors don’t pay attention to filter performance anyway.

Rather than going with a cheaper filter, the way to avoid an airflow or energy penalty with higher MERV filters is to increase filter surface area. And the easiest way to do that is by installing filters at return grilles rather than at the handler filter. Filter grilles can be sized to keep restriction to a minimum. But the ducts better be tight since any return side-leakage will bypass the filter. Of course, tight ducts are important for lots of reasons.

2) Mold needs moisture to grow. Since relative humidity is inversely proportional to temperature, closing the door at night could lead to mold if surfaces get too cool and enough moisture is present.

In general, tight homes and homes with humidifiers are at higher risk for excess winter humidity and mold.

3) Differences in vapor pressure (absolute humidity) is what causes moisture in a steamy bathroom, for example, to distribute throughout the house even when there’s little air movement. An gap under the door will allow moisture to equalize across the door even if the gap is too small for air pressure to equalize while the air handler is on.

(#4 later)

4) ASHRAE defines the comfort

4) ASHRAE defines the comfort range between 40% and 60% RH, but where you want to be within that range is necessarily different in winter than in summer.

In summer when it’s humid outside, there’s a cost to maintaining RH at the low end of the range. As long as RH stays below 60%, people and buildings are generally happy. I typically design to 55% in humid climates.

In winter, RH needs to be a lot lower to protect buildings from condensation and mold. Before we started making buildings super-tight, we didn’t need to worry so much about high winter RH since cold air infiltration tends to overdry the air. So much so that humidifiers are often used to bring RH into the comfort range. However, if we allow too much moisture to accumulate during cold weather, the first red flag will be wet windows, or mold growing in closets or behind furniture.

As we make buildings tighter, high winter RH is becoming more of an issue as internally generated moisture can accumulate. At the same time, we put more insulation in the walls, thus making sheathing and other outboard building components colder. So when that accumulated moisture migrates into wall cavities, as it will, it’s more likely to find a condensing surface. Hidden condensation inside a wall is definitely not something you want to happen! So we have to design the shell to protect against this, as well as use ventilation to keep winter RH under control. This stuff is a big part of what building science is about.

So what’s the ideal winter RH level? That depends on a lot of factors… window u-factors, indoor temps, how evenly the home is heated, use of setback, integrity of vapor retarders, R-value of any exterior insulation, how tight the ceiling is, and and how well the attic is ventilated. But the biggest factor is how cold it gets outside. A home that can get away with 50% RH when it’s 45F outside may be in trouble at 35% RH when it drops below zero.

In most cases, I think 40% is a safe “cold weather ideal”, whereas 50% is pushing your luck.

I wish to find out why my 2

I wish to find out why my 2 stores home is so dusty. It is newly built 3 years ago by a big box national builder. It has a furnace in the basement and one in the attic. Dryer on 1st floor vents directly out. Heating system is just ok, one heating vent does not work in a closet, and never has. There is daily continuous dust, pinkish grey, like tiny fibers, all over the house, especially top floor. My children are all severely asthmatic. Situation has deteriorated so much that we are constantly coughing or I m throwing up. On windy winter days, there is exponentially more dust. We get the dryer vent cleaned annually. We run the dryer daily. We don’t heat at higher than 68-70 in cold winters. Our rooms feel cold all the time. But the dust is the main issue. Insulation in attic is blown in Owens Corning pink fiberglass. Sometimes the dust fibers are white. Is this a duct leakage issue, fiberglass in the air, or what is going on, can anyone please help answer this? I am Swiffering all day long, sometimes 4-5 times a day. Any advice appreciated. Thank you, God bless you.

@ F Ahmed One cannot tell

@ F Ahmed One cannot tell what this is at a distance, but due to your description the first place I would look is for duct leaks in the upstairs unit.

@FAhmed: adding to what John

@FAhmed: adding to what John said, leaks in the attic return ducts would suck in dust and insulation fibers. If your filter is at the return grille, then the dust/fibers would bypass the filter and be distributed to the upstairs rooms. No doubt some would find their way to the downstairs as well.

I suggest hiring an energy auditor (a HERS Rater or BPI certified auditor) to do a duct leakage test and inspect the ducts for obvious leakage points. It may be as simple as a disconnected duct.

I have somewhat of an

I have somewhat of an opposite problem. I have a 2.5 ton HVAC servicing 450 square feet, no not my install.

When the unit comes on it blows the bed covers off. The room adjoins a large open den space, with its own HVAC.

The air handler at risk is in an adjoining garage.

My idea, when guest are using the bed room , I would have an air escape duct in the garage that I could open to dampen the pressure, and noise in bedroom. When not in use I would close the escape vent, and let it blow away in bedroom. Ideas please.

@PM, it would be a shame to

@PM, it would be a shame to waste energy by diverting supply air to the garage. I would look for a way to service the den and bedroom from one of the systems and decommission the other.

PM: In

PM: In addition to what David said, consider also that you’re pressuring the garage and depressurizing the house. That can drive pollutants from the garage into the house. See this article:

Are You Making These Mistakes with Your Garage?

.

PM. I’m with David. Add more

PM. I’m with David. Add more duct to the other unit and shut the other one down.

I have a split level house.

I have a split level house. The downstairs gets very cool in the summer when running the air conditioner. To reduce the cold downstairs, which is very cold and makes you want to wear winter cloths, we shut off the vents downstairs so that only only the upstairs gets air conditioning. After reading this, I now realize that is not the best solution. If I were to shut off the cold air return downstairs along with the vents, would that make a difference? There is a cold air return upstairs as well. I am not sure how to regulate the temperature up and downstairs as the thermostat is only located up stairs. Any ideas outside of purchasing a whole new system?

Great explanation! It’s easy

Great explanation! It’s easy to think you’re saving energy by closing a vent because it seems like you’re turning off the heating or cooling in a room, but this is far from the case. If you’re looking to save energy and money on air conditioning or heating, you’re better off to change the thermostat a bit. Heating or cooling a few degrees less makes a significant difference.

Keen Home got a $7500,000

Keen Home got a $7500,000 investment on Shark Tank for their “Smart Vent” controlled by your iPhone. Hopefully they did their due diligence and bailed before they funded this bad idea.

The LBNL paper by Iain Walker: http://epb.lbl.gov/publications/pdf/lbnl-54005.pdf

Concludes:

“The closing of registers led to an increase in energy use…”

“The reduction in building load due to not conditioning the entire house was more than offset by increased duct losses due to duct leaks.”

It is not hard to figure this stuff our in advance. Why don’t they work on some real problems, like how to sell real conservations measures that actually work. Our industry knows what they are but gizmos have an elan that sweat and toil in crawlspaces and attics don’t because that is where the work needs to get done most of the time.

Even Consumer Reports gave it a mention and they should be able to test these things easily.

CES 2015: Ecovent And Keen Home Smart HVAC Vents –

While this does not

While this does not necessarily apply to multistory buildings, it is interesting to see it claimed that 14.4% reduction in energy usage (not just runtime – energy consumed) was achieved.

http://www.cs.virginia.edu/~whitehouse/research/buildingEnergy/sookoor13roomZoner.pdf

It should be noted that this is with a multistage system. It also cites the Berkeley study and picks up where that leaves off as that study left a number of opportunities unexplored.

Hey everyone! <

Hey everyone!

I wanted to jump into this conversation to clear up a few things. Firstly, we’re not developing the Smart Vent in a vacuum. A very supportive community of HVAC experts, controls theorists, and scientists have contributed to building the Keen Home Smart Vents. For example, we were awarded a research grant by the National Science Foundation in 2014 (you can read the abstract here: http://nsf.gov/awardsearch/showAward?AWD_ID=1448573). We have also based a lot of our own research on this study from the University of Virginia, which was also supported by the National Science Foundation: http://www.cs.virginia.edu/~whitehouse/research/buildingEnergy/sookoor13roomZoner.pdf.

We agree that closing standard air vents can have (negative) unintended consequences. We are very familiar with the LBL study (our controls engineer has a copy on his desk), and we referenced this EV piece while researching a post on vent closure that we posted to our blog in April (https://medium.com/@KeenHome/the-downside-of-closing-air-vents-and-how-we-solve-it-377c6f18c703). With Smart Vents we have created a system that does more than just open and close vents from a smart phone. Keen Home Smart Vents actually monitor pressure and temperature conditions in the ductwork, allowing them to learn a homeowner’s HVAC system and automatically open or close to avoid over heating, over cooling, and excessive pressure build up in the ducts. Unlike standard vent registers that stay closed until you manually open them, Keen Home Smart Vents can work autonomously to safely make a home more comfortable.

I’m happy to answer any questions anyone might have. Feel free to ask her or send me an email any time or day – my personal address is nate@keenhome.io.

Hey, Nate, thanks for chiming

Hey, Nate, thanks for chiming in.

I read the all the papers you quoted and your blog where you clearly state the problem with several major errors but then go on to say the Smart Vent magically solves those problems. It is clear to me that you, your “community of HVAC experts, controls theorists, and scientists” do not understand residential HVAC systems. The propositions in the paper from Virginia are perfectly reasonable if duct work is virtually airtight and if more than sufficient air flow is going through the blower. Neither is true by a wide mark.

Let’s just tackle the energy saving issue only. Running some typical numbers will serve to demonstrate the problem. I have inspected 100s of systems as have readers of these posts and we know these details to be true. IECC 2009 Code requires maximum leakage of 8 cfm of duct leakage to the outdoors per square foot of floor area. 100s of 1000s of duct leakage tests have been performed on existing houses and our industry knows they don’t even come close to code. So let’s run an example to see what you’re up against. I am writing about houses with ducts in attics or crawlspaces. Where ducts are entirely inside the house, energy losses are much less.

Take a 2000 sq ft house with a 3 Ton system blowing 1200 CFM with 0.5 inches across the blower. If the duct loss measured at 0.1 inch is 12 CFM/sq ft (almost up to code. Many are much worse), total duct losses to outdoors at say 0.2 inches would be 364 CFM representing a simple duct loss of 30% of each conditioned CFM. In other words, 30% is simply going outdoors or sucking air in from outdoors. If the home had a house leakage of 7 ACH, and all the leaks were supply leaks the CAZ pressure would be -4 Pa which will backdraft many naturally vented hot water heaters.

Now, let’s look at how the Smart Vent makes this even worse. If 30% of the registers have Smart Vents closed, flow through blower drops to 1050 CFM with a pressure across the airhandler going up from 0.5 to 0.74 inches. If the pressure across the leaks could go up to say 0.44 inches, then duct leakage to outdoors soars to 582 CFM, where total duct loss to outdoors increases from 30% to 57%. Many are better but some are worse.

You could argue with all these numbers but the mechanism of loss is still the same. Some houses better and some worse but overall, it is almost impossible to save anything with leaky ductwork. Ducts in the USA leak a lot!

Many of the people contributing to this blog have been fighting to mandate duct testing on every new home because it’s the number one energy waster. Your device will simply make it even worse. Yes closing dumb vents is a bad idea but nothing you’ve written so far indicates you really understand the problem or that your device corrects it that much. If your Smart Vent was smart enough to open at say 0.15 inches instead of the 1.2 inches in your blog you could say you’re making a bad situation not quite as bad. Incidentally at 1.2 inches, duct losses would be so great that the CAZ would go above -30 Pa and make everyone in the home sick. Or dead. You got that one really wrong.

There are two problems for Keen Home.

1. Virtually no one will save anything. Most energy bills will go up.

2. Systems will still overload and burn out

3. CAZ limit will be exceeded causing dangerous conditions in people’s houses.

The difference will be that you’ll have your name on those devices and you told consumers you had it handled. In Kevin O’Leary’s words, you will be “sued into the Stone Age”.

I admire your courage in going after some peer review. I see no one with experience and/or knowhow embracing your idea. I would love to learn the names of your advisers since I know most of the researchers in our industry but understand that you’ll not let us know who they are. This Shark Tank will be way tougher than the first one you entered.

Concluding, you have not shown any mechanism to save energy with Smart Vent. Your responses indicate you don’t understand residential HVAC as it exists in the real world.

Bright point is, you have been able to manufacture and sell a Vent for $85 (I believe) that according to your statements, monitors room temperature, system air delivery temperature, pressure and proximity. With WiFi capability. That IS truly amazing. And you appear to be great marketers. There must be a direction you can apply your talents towards to good effect. It might be impossible to end it now but I can assure you that it will not end well for all parties. My concern is protecting my industry from claims I know are false. We have a hard enough time selling conservation as it is. Why cannot we get your bright minds on the real problems we face?

Oh, and I didn’t even touch on the other issues.

The UVA paper isn’t a

The UVA paper isn’t a proposition, it was an observation during an experiment.

The irony with your made up numbers and suggestions – that systems are way leakier than they are supposed to be and way over built for the spaces they are conditioning, is that it sounds like the HVAC guys should be sued into the stone age for improperly installing all of these systems. You said it yourself, the UVA results make sense if the system is properly sized – so the problem is not the company(s) that are putting a radio and motor on vents (that all already have levers and louvres for flow adjustment), but instead its the people – ‘the experts you are friends with’ – that have installed oversized leaky systems for decades. But now you are telling us we should believe you and your friends that didn’t know what you were doing in the first place?

And while energy savings will vary from home to home, geography to geography, and user to user, the reality is that this are serving as a self balancing system. You may not like that because your manufacturing company that you own and operate (https://www.linkedin.com/pub/colin-genge/14/380/443) would stand a lot to lose if you couldn’t sell your equipment to contractors to manually open and close vents to balance airflow.

Joe M.:

Joe M.: Clearly you don’t know much about the HVAC industry and how bad things actually are. Also, you seem to be new to this blog because I’ve been writing for years about how messed up the HVAC industry is and the problems with the crappy systems in homes. Here are a few for you to read if you’re so inclined:

Why Won’t the HVAC Industry Do Things Right? from 2011

Release the Kraken! — The Ductopus Is Bad for Air Conditioning from 2012

The 7 Biggest Mistakes That HVAC Contractors Make from 2013

That doesn’t mean that there are no good HVAC contractors. There are plenty but they’re the minority. The HVAC pros who read and comment in this blog are in that group.

You seem to think you’ve uncovered some big hypocrisy here when in fact you’ve just exposed your ignorance of the industry. And your attempt to discredit Mr. Genge is equally ignorant. I didn’t even know his company made balancing dampers, but if they do, I’m sure it’s a tiny fraction of their main business – selling pressure testing equipment.

How many duct systems have you tested, Joe? Have you measured air flow? Static pressure? I’m guessing your number’s got to be close to zero because those of us who have measured know air flow in ducts is a serious problem.

Joe Martin

Joe Martin

I spent a lot of time running an excel model on a typical residential duct system. The small amount of energy saved by satisfying the thermostats set point earlier is overwhelmed by increased duct losses. You should be thanking me for giving you a crystal ball into what will happen in the future. Your vents appear to be well made but have no application in the hvac world as it exists today. If systems were designed from new to accommodate them, you might have something.

Yes the product makes sense if units are properly sized and are free of leaks but none of them are. Even the new codes permit enough duct leakage to make your Vents increase duct leakage and eliminate any savings.

Our company sells pressure relief vents for commercial applications where they are used to relieve pressures of clean agent fire suppression discharges. We will never have one installed residentially. They are a small piece of our market for duct leakage testing systems. Since we have sold about 10,000 residential duct leakage measurement systems in the US and done tech support on them, we know a fair bit about duct leakage. As Allison said, how many homes have you measured duct leakage on?

Our sales are driven by code compliance and are not affected in the least by your Smart Vent sales.

Nate talked about experiment on your “test home”. Sounds like testing might be a bit late since you’re ready to ship soon. I can see how Keen Home could be getting nervous about the existing conservation community not embracing your efforts. Hopefully you can take our comments to heart but doubt that because so far you have merely tried to snow us with marketing talk consisting of a lot of pretending that you’re taking your detractors comments into account.

Joe M. Nobody I am aware of

Joe M. Nobody I am aware of is against innovation that proves by testing and data to save heating and cooling energy. For some time scientists in this field have steered us away from basing what is done on theory, but rather from actual tests with measured results.

It would be helpful to name your experts and bring them into the conversation so we can share these data. In the mean time take a mining expedition into our website. Lots of monitored data, reports, papers, etc.

So I went and read the UVA

So I went and read the UVA paper and found (if I understand it right) that the savings projected was in heating, not air conditioning, and that there was no house — at least as far as I could find. It seemed to be a simulation.

The paper mentioned an experiment in Danville by others that measured savings. I read that paper and found that it too was in heating with a furnace and was only a few days. Basically what it found (if I am reading it right) is that if you direct all the heat from the furnace to a single zone, then the furnace runs less. I think we can all agree that is true if the thermostat is in that zone. This seems to be coming from researchers who are looking at control theory mostly on a theoretical basis.

Clearly the bigger issue when

Clearly the bigger issue when adjusting or shutting vents is with DX compression cycle cooling.

Zone control systems have been around for decades. In theory they’re great but in practice, very few residential contractors understand how to design and install them correctly. Too much potential to make things worse.

In particular, the ducts and zone logic must be designed so that the correct amount of airflow is maintained at the cooling coil. Bottom line is that the only (and best) way to get air to where its needed is through proper design.

Joe M. are you still there? I

Joe M. are you still there? I know it can be a pain to learn something that contradicts what is in our heads — happens all the time. Nice book to read the first few chapters: Ignorance — How it Drives Science

Some new readers such as Joe

Some new readers such as Joe and Nate may not realize how ridiculously committed contributors such as John, Allison, David and myself are to energy conservation. We WILL support ideas that work.Big time. Just give us the facts and we’ll help you based on endless experience.