Why Do Airtight Homes Need Mechanical Ventilation?

I’ve written a couple of articles recently about the complexities of mechanical ventilation and the battles going on regarding when to install it, how much to ventilate, and whether ASHRAE 62.2 is worth all the resources we’re throwing at it. (If you missed the debate between Michael Blasnik and Joe Lstiburek in the comments of the last one, you should go read it. It was the Building Science Super Bowl this weekend.) Those articles were aimed at pros in the building science/green building/home performance field. Today, it’s time to step back and remember why we’re even talking about ventilation.

Why not infiltration?

In the article I wrote about how blower doors can’t tell you how much mechanical ventilation you need, an important question came up in the comments. Remodeler Doug Thompson asked:

“Can someone explain in simple terms just why its so much better to use mechanical ventilation in a tightly built house to provide the same quantity of air as infiltration might give us from a leakier home? This, of course, assumes that we’re talking about exterior air of comparable quality and temperature.”

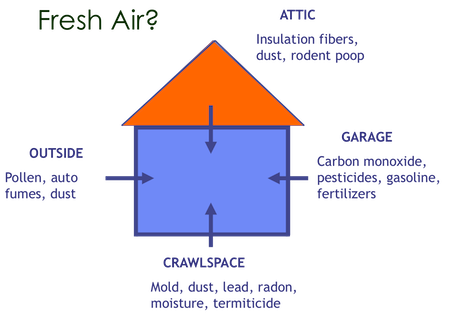

As I wrote a couple of years ago, this idea that a house needs to breathe is a myth. In other words, leaky homes don’t necessarily have good indoor air quality. Why? Let’s start with some of the typical pollutants you might find in a home’s air:

- water vapor

- radon

- mold spores

- carbon monoxide

- VOCs

- formaldehyde

If all of those things came from inside the house and nothing bad came from outside, then relying on infiltration might work. They don’t and it doesn’t. If you try to rely on infiltration for ‘fresh’ air, you’re likely to be disappointed.

The other problem with relying on infiltration is that you don’t know how much air you’re getting. This was one of the big points of contention in the Blasnik-Lstiburek debate. Blasnik did “a few quick calculations (using all 1,020 TMY3 stations)” and used that analysis to say that in a moderately leaky home, the number of hours per year that a home goes below 50% of the most used ventilation requirement (ASHRAE 62.2) is pretty low.

Still, his simulation assumed a two-story house. One-story homes on slab foundations are shorter and will have less stack effect, so the hours per year of low infiltration will be less. And even for all those hours when the infiltration is above the ventilation requirement, we have to consider the source. If air is leaking in from the attached garage or moldy crawl space, it’s probably making the home’s air worse, not better.

How tight is tight?

OK, so if you accept that relying on infiltration is a bad idea, how do you know if your home is tight enough to bother with installing mechanical ventilation? I wish I had a good definitive answer that worked for every home, but this is where a lot of the debate about ventilating homes is focused. A lot of homes were air-sealed with ARRA funds over the past four years, and this question came up a lot.

The weatherization programs until recently used something called the Building Tightness Limit (BTL) or Building Airflow Standard (BAS) to determine if a home needs to have a mechanical ventilation system installed. It was based on the older ASHRAE standard, 62-1989. There were two ways to calculate it, but most of the time, it came down to translating blower door results into ‘natural’ air changes per hour (ACHnat). If the house had more than 0.35 ACHnat based on the blower door test, the weatherization crew did not have to install a ventilation system.

into ‘natural’ air changes per hour (ACHnat). If the house had more than 0.35 ACHnat based on the blower door test, the weatherization crew did not have to install a ventilation system.

Lstiburek thinks (and I agree) that’s a bad way to decide because converting blower door results to natural air changes is not very accurate for ventilation needs. Michael Blasnik disagrees. Lstiburek wrote in a comment this weekend, “the air change rate from hour to hour or day to day does not correlate to a blower door number.” He’s talking about variations that matter on the scale that ventilation requires – hour to hour.

Back to the main question here, I think most people would say that a home with 3 air changes per hour at 50 Pascals (the pressure used during a blower door test, abbreviated ACH50) is definitely tight enough to require a mechanical ventilation system. If the home leaks at the rate of 20 ACH50, a ventilation system sized to ASHRAE 62.2 levels would be swamped by infiltration much of the time.

For now, we can summarize by saying that leaky homes need air-sealing. When they get tight enough, they need mechanical ventilation. Many homes fall into that grey area with the fuzzy borders somewhere in the middle between leaky and tight.

More important, though, we need a better way of deciding when to install mechanical ventilation. For new homes, it’s pretty easy. “Build tight and ventilate right.” ASHRAE 62.2 works for this. With existing homes, we need a method that’s based on indoor air quality in addition to how much air leakage a home has.

Related Articles

A Blower Door Can’t Tell You How Much Mechanical Ventilation You Need

Residential Ventilation Smackdown — The Battle Over Simplicity

This Post Has 7 Comments

Comments are closed.

this subject has been

this subject has been something I’ve worked with for years. in existing homes..it is hard to get the house tight enough to require fresh air. but when you do…how to address it??

one thing that would really help those of us in the field is to have a set ach standard.

my state uses .35

other states use much more realistic numbers for air changes per hour.

over the years I’ve tried different stratagies. erv..which is a high cost, plus added utility costs per month. passive intake with barometric damper..which I really like. no motors to replace, no cost to operate.

duct with zone damper,

and whole house dehumidifiers with fresh air intakes.

the latter is the best way in my hot humid climate..but high cost puts this and erv out of a lot of people’s budget. and you have more equipment to replace/repair and the operating costs.

having one standard of tightness, one that isn’t fudged to do cya…would make life simpler for raters in the field.

“Just pick one!!”

personally, after all these years in existing market I find that when the blower door number is equal or less to sq ft of house..you need to look at fresh air options.

lately I’ve been learning about measuring CO levels.

as we breathe we exhale CO,

so with amount of people in the house, & factors for any gas appliances…this may prove to be worthwhile investigating.

just my pov after 15 years in the energy rating trade.

good article..and the previous article also. keep up the good conversations Alison!

Allison,

Allison,

Your customary excellent and thought provoking work on a topic that crys out to be addressed in existing homes (OK, how can mechanical ventilation cry out ? :-). Unfortunately, that’s all I have to say on the subject and I’ll watch for additional input from you and thoughtful posters like Debbie.

Probably should start a new thread here, but since you are the one with the dirty Rosarch inkblots (old Maxwell Smart joke), oops, I meant picture of a water heater vent on an accompanying link, it got me wondering about something.

When my elderly neighbor recently asked for help with her 10 year old (as is house) DHW, I quickly realized it was time for the big kids. During his visit, the contractor observed the DHW vent went from 4″ atop the heater, to perhaps 6″-7″ via several angles and adapters on the way through the ceiling. The vent was clearly corroded from condensate, which had also run down and destroyed the burner, and he contended the expanding vent diameter enabled reduced stack,effect and subsequent excessive cooling of exhaust gas contributing to failure of the DHW burner assembly from corrosion (pilot would not remain lit).

At his suggestion, in addition to the DHW, my neighbor had the superficially corroded vent completely replaced with 4″ duct.

Your thoughts?

Best wishes

Debbie:

Debbie: Glad you liked the article. It’s important stuff, IMHO. One thing you shouldn’t lose sight of, though, is what Einstein said about simplicity:

“Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.”

Steve W.: If they’re concerned about draft and have replaced equipment, surely they tested for draft. Right?

Can I ask a really dumb

Can I ask a really dumb question? I get how mechanical ventilation sucks. i.e. there’s a fan, it sucks – air out. And I’ve heard a lot of suggestions that a nice efficient bathroom fan will do the trick for many homes, i.e. exhaust-only ventilation. But if “normal” infiltration brings in all kinds of yuck, presumably just turning on a fan would too. What’s your thinking on this? Do you need passive air inlets to avoid sucking in the yuck through random cracks? Or is an HRV/ERV the only way to go?

Eric: If

Eric: If you know where the leaks in the building enclosure are and if they’re not connected to spaces with bad air (i.e., garages, moldy crawl spaces…) and if you’re not in a hot-humid climate, exhaust fans might work for whole house ventilation. You’re right that a negative pressure ventilation system isn’t much different from relying on infiltration except that you create the pressure difference.

Regarding passive air inlets, it’s probably best to save your money and not install them. Read what Martin Holladay says about them in this article on ventilation.

Yes, an HRV/ERV balanced ventilation system is the best way to go. It’s more expensive, though.

I agree that mechanical

I agree that mechanical ventilation is needed in tight homes. Please give some examples of economical affective methods of ventilation systems. I manage the Weatherization Program for Kalamazoo County and we could use some ideas and resourses for retro-fits. I am aslo a new home builder and I would use some ideas in new construction also. Please advise. Builders, what have you found that works well and cost affective?

Greg – greg.ferris25@hotmail.com

Greg F.:

Greg F.: Thanks for your questions/requests for info. For weatherization, one of your best options is the Panasonic Whisper Comfort ERV. It’s about $300 and can provide about 40 cfm. Another option is to use a positive pressure, central fan integrated supply (CFIS) ventilation system. To do so, you connect a duct to bring air from the outside to the return side of the HVAC system. It and the Whisper Comfort are your least costly choices. You can read more about different types in Armin Rudd’s Ventilation Guide, available from Building Science Corporation for only $20.