Can Uninsulated Ducts Damage Your Siding?

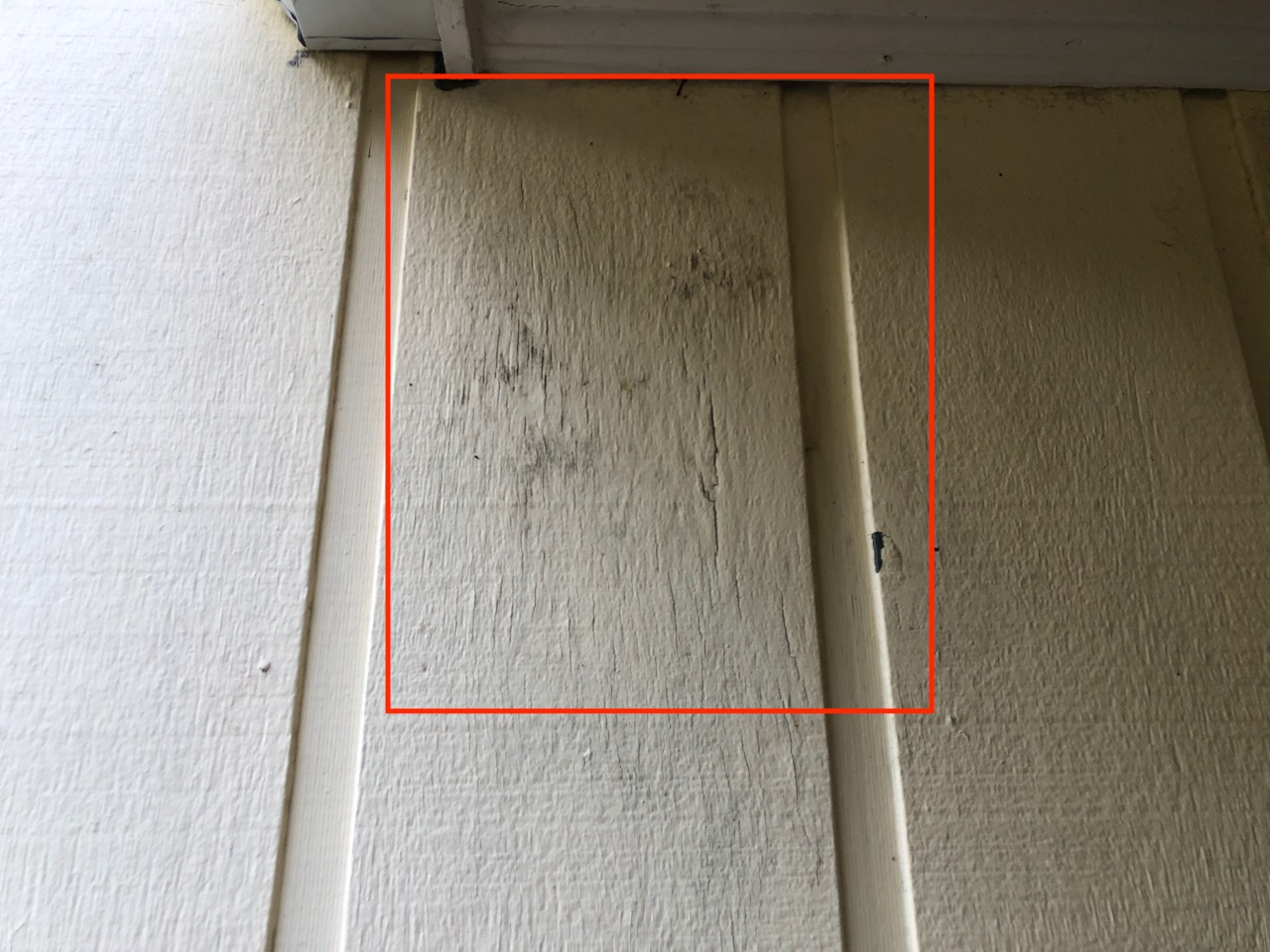

I won’t keep you in suspense here. The answer is yes, absolutely. Uninsulated ducts damage your siding in a humid climate in some cases. I recently visited a house in Atlanta that has that very problem. If you haven’t scrolled down yet, look at the photo above. Stare at it for just a bit, and see if you can find where the uninsulated ducts are in that wall and how many there are.

If you didn’t find them all, I’ve highlighted them below. The paint is discolored in those areas and even peeling a bit. This house was built in the 1960s, so they’ve probably had to repaint quite a bit more than they would have liked over the past five decades. And who knows how rotten the sheathing beneath the siding is.

The problem wasn’t limited to that one side of the house, though. Below is another spot right by the front door.

Why does this happen?

As I wrote in an article on the problems with ducts in exterior walls, “Putting cold air into an uninsulated piece of sheet metal in a poorly air-sealed enclosure is a recipe for condensation and mold for homes in humid climates.”

The photo below shows what’s between the siding and the drywall. Most houses here in Georgia have 2×4 walls so there’s no room for insulation. That sheet metal boot gets very cold when the air conditioner is running. If the exterior sheathing behind it isn’t insulated, the sheathing gets very cold. And that makes the siding on the outside cold, too.

When the sheathing and siding get cold in a humid climate, the wood sucks up moisture from the air. Wet wood is a great place for mold and other stuff to start growing. In fact, I was called to look at this house because of moldy, musty smells and a homeowner who developed health problems after he moved into the house. There was more to his problems than just the uninsulated ducts in exterior walls, though.

What can you do?

You don’t want uninsulated ducts to damage your siding, so you have to apply a little building science here. As I wrote in an article on how to prevent humidity damage, surfaces in contact with humid air—the siding and sheathing in this case—need to be kept warm enough to minimize the accumulation of moisture from the air. To accomplish that, you have a few options:

- Put insulation between the duct and the sheathing or under the siding.

- Move the air conditioner supply vent out of the exterior wall.

- Abandon the exterior wall vents by installing a new heating and cooling system with new ducts and vents. (This is what I’ve done in my house.)

The second of these methods will generally be easier and less expensive, though none is easy. There’s not a quick fix here. The good news is that this is mainly an older home problem. I’m not going to say there aren’t any new homes out there with uninsulated ducts in exterior walls, but it’s really uncommon now.

Do you have any mysteries at your house where the paint is peeling from your siding? Maybe this is the answer. Check to see if those spots line up with where the vents are, as they do in the house shown above.

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard. He has a PhD in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

The Third Worst Place to Put a Duct

A Line in the Sand — The Dew Point Duct Duel

Buried Ducts Risk Condensation in Humid Climates

The Lesson of the Raining, Dripping, Crying Duct Boots

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 10 Comments

Comments are closed.

Allison, you seem to imply that this issue is due to air leakage from the duct, but your insulation solution seems to imply that it is due to heat conduction by the duct and materials. In your opinion, is the issue due primarily to one or the other mechanism? When you say put insulation between the duct and wall, you know that someone is going to grab a can of foam insulation and inject it between the two. I can see issues with that. What about you?

Matt, the leakage I was talking about was outdoor air getting into wall cavities, where it can condense on the uninsulated sheet metal. Duct leakage certainly can make things worse, but it’s the outdoor air with all its humidity near the cold sheathing and siding that causes this problem. If that outdoor air gets into the wall cavity—and it usually does in old houses with ducts in exterior walls—then the condensation happens inside the all, too.

You wrote: “…someone is going to grab a can of foam insulation and inject it between the two. I can see issues with that. What about you?” Yes, I can. That’s not what I meant by that statement, but yes, if someone interprets it that way and does what you suggest, they probably won’t solve the problem. At least here in Georgia, the boot fills up the whole wall cavity so they wouldn’t really be able to put foam in that space. At best, they’d get foam around the edge. I’ll see what I can do to clean that recommendation up. Thanks for pointing that out, Matt.

A great many building science fails seem to arise from a single stark choice:

“Manage the dewpoint, or it will manage you!”

Curt, that’s a great way to put it. Humidity problems are all about keeping humid air away from cool materials, with “humidity” and “cool materials” defined in terms of dew point. Of course, bad flashing, roof leaks, flooded basements, and other liquid water problems cause more damage than humidity problems, but water vapor still claims its share.

Allison,

I see this sometimes in 2×6 exterior walls here in the northeast where the ducts are wrapped with “bubble wrap” and at best the sides are stuffed with batt insulation.

What do you think the minimum r-value should be for these ducts? Should “bubble wrap” be considered insulation?

Great question, Gordon. I agree with Curt’s recommendation for code-minimum fiberglass duct insulation with a vapor barrier. Bubble wrap by itself is about R-1, so it wouldn’t meet the code. If it’s installed with proper air spaces, it might work, but those gaps are hard to achieve and even harder to maintain.

The bigger issue is that ducts shouldn’t be in exterior walls unless you have enough insulation outboard of the duct to meet the code requirement for that wall. It also needs to be air sealed to keep humid outdoor air from getting anywhere near the duct.

IMO, duct insulation should consist of a sufficient thickness of an insulating material to meet R-Value code for the specific application, typically R4,6,or 8. The insulating material is nearly always fiberglass since it meets important flame spread and smoke development codes.

Duct insulation should then be covered with a continuous vapor impermeable barrier. This serves as a secondary defense against air leaks, but, much more importantly, prevents the insulation from being wetted by condensation. Typical outer layers include mylar, metal foil, reinforced scrim tape, or fairly thick polyethylene (similar to sub-slab vapor barrier film)

In theory, an assembly consisting of “batts and bubble wrap”, properly installed, might meet requirements, but I’m skeptical what you describe performs properly.

>”I’m not going to say there aren’t any new homes out there with uninsulated ducts in exterior walls, but it’s really uncommon now.”

(OK, time to pet the peeves again I guess… 🙂 )

ANY ducts (even insulated ducts) in exterior walls is just plain stupid- both an energy waste and an invitation for future problems. In a sane world gaps in the building insulation like that would not exist, punching holes in the building insulation to route HVAC ducting (or even install air handlers) outside the thermal & pressure boundary of the house just wouldn’t happen, but they do.

Ducts & air handlers above the floor insulation in vented attics, anyone? 😉

How about ducts & air handlers in basements or crawlspaces under the floor insulation?

Why not just put it all outside, up in the air? They’re out there.

A project I advised on in central MA a handful of years ago had barely a insulated flat roof /cathedralized ceiling (no attic, thus) and a finished walk out basement that housed a tiny mechanical room with a 200KBTU/hr hydronic boiler and a 50 gallon water heater. Cooling was provided by 9 tons of commercial building style AC package units (a 4 ton and a 5 ton) mounted above the roof, with a duct sculpture (insulated with R6) running to ceiling diffusers and a few ceiling return grilles. It had enough heat & coolth to cover the loads, but it was MISERABLE to live in! The AC was deafening when running (but oversized to the point of not adequately controlling latent loads), and when the radiant ceiling heat was running the house reeked of bitumen roofing indoors. After every snowfall (in a city that will sometimes get 10+ feet of total snowfall over a winter) the snow melt formed ice dams & icicles, sometimes big enough to a hazard to cars or people below when they fell.

It took some convincing (the owners were ready to give up and sell), but building a very low slope gabled roof above the existing roof with 6″ of polyiso and new membrane on the new roof deck, creating a cramped crawl-attic to house RIGHT SIZED (per Manual-J) mechanicals, which consisted of a 60KBTU/hr 2 stage furnace and either a 3 or 4 ton (just one) AC unit. Combined with some window upgrades and spot insulation fixes that great looking but downright miserable uncomfortable energy hog Mid Century Modern (circa 1958) transformed from being one of the least comfortable houses ever, to something VERY comfortable in all seasons, using less than half the heating & cooling energy that it had previously. (This was not a project for the faint of heart or light of wallet, but it was later sold at a net gain despite only staying 3-4 years after fixing it.)

The point being- bring ALL of the mechanicals COMPLETELY inside the thermal and pressure boundary of the house, and right size the equipment. That makes it possible to actually control heat & moisture flows to properly condition the living space, and avoids a whole range of problems for the house itself. The practice of installing ducts in vented attics or exterior wall stud bays needs to just end!

Wow, Dana! I was uncomfortable just reading about how uncomfortable that house was. And horrified at how they tried to solve the building enclosure flaws with mechanical systems.

Yes, ducts and air handlers need to be inside the building enclosure. Absolutely! Thanks for making the point about that here in the comments since I glossed over it in the article.

This problem is elevated when using variable/multi speed equipment due to the colder air. Especially when running wall stack in roof rafters.