Foam Insulation, Global Warming Potential, and BS

I’ve been reading a lot of BS lately. No, I’m not talking about blood sugar. It’s brain science that’s captured my attention. Understanding how the human brain works, why we do the things we do, and what common illusions often lead us astray. What I want to talk to you about today, though, is foam insulation and global warming, but first, we have to talk about calamari.

I’ve been reading a lot of BS lately. No, I’m not talking about blood sugar. It’s brain science that’s captured my attention. Understanding how the human brain works, why we do the things we do, and what common illusions often lead us astray. What I want to talk to you about today, though, is foam insulation and global warming, but first, we have to talk about calamari.

Have some calamari

This has nothing to do with any visual similarity between calamari tentacles and grey matter. Instead, let me relate a story first told on This American Life in 2013. Let’s say you go to a restaurant and order fried calamari. The server brings it and you and your friends start munching away. Well, all but one of you anyway.

Your friend Kim is just sitting there, not partaking of the fried delicacy you’re all enjoying so much. Even worse, he’s grimacing while watching the rest of you eat. So you ask him what’s up…and then wish you hadn’t.

Calamari served in restaurants, he tells you, is often not calamari at all. It’s really hog rectum! Farmers package it as imitation calamari and that’s what a lot of restaurants serve now, he says.

Disgusting, right? A lot of people who have heard that story, first taken mainstream on that 2013 This American Life episode, think so. The truth, however, is that there’s really no evidence to support that claim. It’s an urban legend. So will you eat calamari tonight?

I’ll come back to the calamari in a bit, but first let’s look at foam insulation and global warming. I promise it’ll make sense when I’m done here.

Foam insulation and global warming

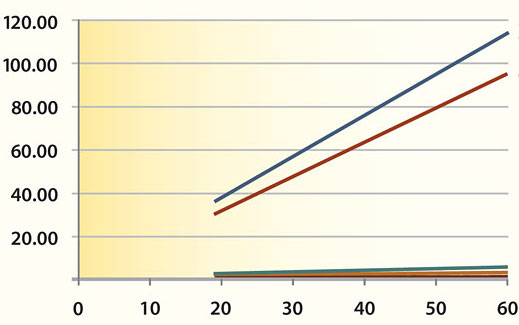

Last November I was at a conference when one of the speakers showed a graph with the same data you see below. In the graph, you can see two lines way above the others. And they increase rapidly, whereas the other lines are much flatter.

As it turns out, the quantity plotted on the vertical axis is a bad thing. That means whatever it is that’s represented by those two lines at the top must be really bad. I’ve seen these data show up over and over at conferences and in articles since 2010.

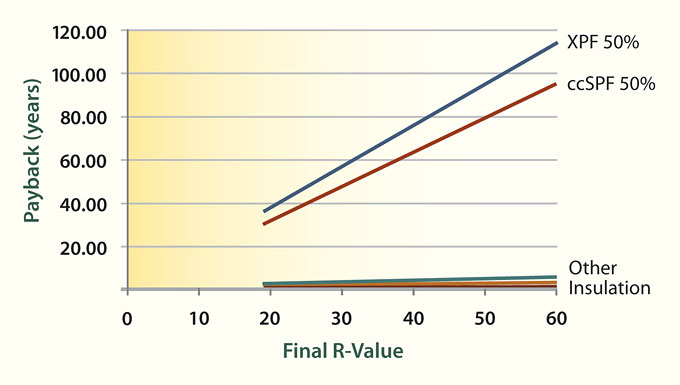

The graph above comes from Alex Wilson’s article, Avoiding the Global Warming Impact of Insulation. In it he showed results from calculations of the “payback” of various types of insulation. It wasn’t financial payback, though. He wanted to know how long it would take for insulation to save enough energy to offset the global warming impact of the insulation itself.

Here’s an easier way to understand it. Using insulation saves energy. (Duh!) Saving energy means power plants put less greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. But insulation takes energy to make, too. That’s the embodied energy. And some types of insulation use greenhouse gases that can escape into the atmosphere.

Wilson wanted to quantify the relationship between greenhouse gases prevented and greenhouse gases emitted. You can read his article and see a summary of what they did. The graph below is perhaps the main result. It’s the same graph as above with the labels included this time. Payback is on the vertical axis, and lower is better.

The two insulation materials he vilified were XPS (not XPF), which stands for extruded polystyrene, and ccSPF, which is closed cell spray polyurethane foam. His calculations showed they would have very long payback periods, and the more of it you used, the worse it got.

“Assumptions are key in this analysis.”

When I first read Wilson’s article in 2010, I thought I must have missed something. So I read it again, more thoroughly. I still didn’t see he got from point A to point B. Even after reading the full article, it just didn’t hold up.

The main problem is they had to assume too much. With a different but reasonable set of assumptions, their results would have looked far different from what they showed. But hey, they told readers upfront that the results didn’t really mean much when they said:

“Assumptions are key in this analysis.”

A few months after Wilson published his article, I wrote a response titled, Don’t Forget the Science in Building Science. In it I laid out the assumptions:

- The manufacturers used high GWP blowing agents.

- The offgassing profile is uniform.

- The lifetime of the product is somewhere between 50 and 500 years, though the article doesn’t say what numbers they used.

You can go back and read my article for more on my original criticism. The main point is that they really had only one bit of information. It was a guess because manufacturers were tight-lipped about exactly which blowing agents they were using, but it was a good guess.

Blowing agents and global warming

Really, it all came down to the blowing agents used in the foam insulation materials. That’s the stuff that turns the liquid chemicals into a foam. Global warming potential (GWP) of various materials is a number that refers to carbon dioxide. For example, methane has a GWP of about 36 over a 100 year time horizon. That means it can trap 36 times more heat than the same mass of carbon dioxide.

At the time Wilson wrote his article, most closed cell spray foam was probably using HFC-245fa as the blowing agent. Its GWP is about 1,000. XPS probably used HFC-134a, with a GWP of about 1400. The other foams use water or pentane as blowing agents, and they have much lower GWPs.

In the calculations Wilson reported, the embodied energy of the various insulation materials had little effect on the payback. The biggest factor was the emission of high GWP blowing agents. (Again, those results were based heavily on the assumptions they chose.) That’s why the ccSPF and XPS lines were so far above the rest.

The times they are a changin’, though. Honeywell has a low GWP blowing agent called Solstice. It has a GWP of less than 5. At the Spray Polyurethane Foam Alliance conference last month, I heard that at least one of the big spray foam companies (Lapolla) is using it. More are sure to follow.

The calamari connection

Now, let’s wrap this up by getting back to calamari and brains. Researchers have documented that when we’re given bad information, we believe it. And when we’re told later that the information was wrong, we still believe it. How many jurors do you think really disregarded a specious comment from a defense lawyer just because the judge told them to?

I haven’t had calamari since I first heard the hog rectum rumor. I’m sure many others have done likewise. Our brains hold onto the initial information, even when it’s shown to be wrong later.

As I said, I’ve seen this bad information about closed cell spray foam and XPS foam board come up many times in the last six years. I’ve spoken up whenever I could to attempt to get people to understand they shouldn’t base decisions on that misleading graph.

Yes, those two types of insulation probably used—and some still use—blowing agents with high global warming potentials. That’s really as far as you can go quantitatively, though. We just don’t have enough data to make the kind of pronouncement that Wilson did.

And yet this notion persists. The brain likes to hold onto those things that get there first. Even when they’re shown later to be wrong. Even when the one thing those products were guilty of becomes no longer true as foam manufacturers switch to low GWP blowing agents.

I’m going to have some calamari this week. How about you?

Related Articles

Don’t Forget the Science in Building Science

4 Pitfalls of Spray Foam Insulation

California Mistakes Put Spray Foam Insulation on the “Bad List”

Image of human brain by Joseph Vimont from US National Library of Medicine; public domain.

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 27 Comments

Comments are closed.

Allison,

Allison,

Thanks for the information and clarification about the XPS and SPF products and their "initial" drawbacks. Both of those products definitely have a place in the building and retrofitting of more energy efficient housing. Plenty of products when first introduced have negativities around their manufacture and use. However, as we become more aware of those negatives, competitive more "green" products are soon introduced. There is nothing wrong with pointing out the negatives of certain products, but it is also important to share information when cleaner products come along to replace the dirtier ones.

Informed people will make the right decisions for the environment and your information can now be used to find and use those cleaner products. Thanks again!

Hi Alison,

Hi Alison,

Thank you for an excellent article. In a recent conversation with a structural engineer, she expressed a different reservation regarding the use of ccSPF. On a project several years ago I called for 2" of ccSPF on the underside of the plywood roof sheathing, backed by batt insulation in the rest of the cavity created by the 14" LVL roof rafters. In the PNW this combination- called "flash-and-batt"- is popular. Her concern is the potential of the plywood sheathing to expand and contract thereby creating a break with the ccSPF, which would allow moisture intrusion. Your thoughts on this?

Allison,

Allison,

Thanks for the information and clarification about the XPS and SPF products and their “initial” drawbacks. Both of those products definitely have a place in the building and retrofitting of more energy efficient housing. Plenty of products when first introduced have negativities around their manufacture and use. However, as we become more aware of those negatives, competitive more “green” products are soon introduced. There is nothing wrong with pointing out the negatives of certain products, but it is also important to share information when cleaner products come along to replace the dirtier ones.

Informed people will make the right decisions for the environment and your information can now be used to find and use those cleaner products. Thanks again!

You’re welcome, Thomas. Yes,

You’re welcome, Thomas. Yes, pointing out the negatives is a good thing. But attempting to quantify something by doing calculations based on assumptions leads to misinformation.

Hi Alison,

Hi Alison,

Thank you for an excellent article. In a recent conversation with a structural engineer, she expressed a different reservation regarding the use of ccSPF. On a project several years ago I called for 2″ of ccSPF on the underside of the plywood roof sheathing, backed by batt insulation in the rest of the cavity created by the 14″ LVL roof rafters. In the PNW this combination- called “flash-and-batt”- is popular. Her concern is the potential of the plywood sheathing to expand and contract thereby creating a break with the ccSPF, which would allow moisture intrusion. Your thoughts on this?

The SPF will follow expansion

The SPF will follow expansion and contraction of common building materials without cracking or delaminating. There are well-known application techniques for transition membranes at the juncture of intersecting building systems, and termination details have been well documented and publicized.

SPF is a remarkable product, especially when installed to the exterior of a building. The SPF acts as the air barrier, vapor retarder, thermal insulation and rain screen (WRB) in one monolithic layer. It is protected by the cladding which can be masonry or metal panels, and should save far more energy and offset far more CO2 than any other insulation type.

One could imitate this performance with foam board, but the boards should be be installed in at least two lifts with seams taped and sealed and offset vertically and horizontally with every brick or facia tie calked and sealed.

Like Allison’s article suggests, it’s probably OK to make the substitution, but why? The next-gen blowing agents are now available. There are very good, well-trained and certified contractors available. And, there are knowledgable and reputable third-party SPF inspectors to verify installation to industry standards on large jobs.

Anything but the real thing might be OK, but it just messes with my head.

Have spray foam manufacturers

Have spray foam manufacturers addressed shrinkage or is that an installer issue? I’ve seen photos of spray foam in stud bays that has shrunk.

Note to Allison: If you’re still afraid of calamari may I suggest you also avoid sausages made with ‘natural casing’. I’m just sayin’ lol

That’s an installer issue,

That’s an installer issue, Kris. I’ve seen — and posted — photos of ccSPF pulling away from framing members. Most installations are fine, though.

I agree with Mac. Closed cell

I agree with Mac. Closed cell SPF can work fine. There have been cases of improper installation leading to shrinking, but that doesn’t happen when it’s done right.

Question everything,

Question everything, superstition exists everywhere and humans share 97% of their DNA with lemmings.

Oh, and 83.4% of statistics on the internet are made up, just like in the spray foam “study.”

Nice writing Allison!!!

Thanks, Ted.

Thanks, Ted.

Great article Allison, thanks

Great article Allison, thanks for another intriguing and well-written post. It is good food for thought, as I’ve had this “spray foam is the worst thing ever” notion embedded in my brain since as long as I can remember, too (likely around 2010).

Thanks for sharing your insight!

Spray foam, like every other

Spray foam, like every other product, has its pros and cons.

Hi Allison,

Hi Allison,

Thanks for being on this–there are situations, especially in retrofits, where we want to use spray foam but don’t want to feel like we’re robbing Peter to pay Paul. My question is–if the spray foam manufacturers know many of us have an issue with the GWP, why don’t they proudly proclaim it if they have left the high GWP blowing agents behind? Anything for a sales advantage, right?

Oh, and I can forget the pig rectum rumor with calamari…it’s the omega-6 oils they typically use for frying that I mind! 🙂

I think you haven’t heard

I think you haven’t heard much because they’ve been slow to switch. It’s not a simple matter of pulling the old blowing agent and using the new one. The new one requires adjustments to the formula. I think you’ll see more companies making the move soon. Lapolla has done so with high-pressure systems already. Fomo has made the change with their low-pressure foam.

I guess I should not have

I guess I should not have given this lecture yesterday http://www.treehugger.com/slideshows/green-architecture/natural-materials-are-coming-dominate-green-building/

Good write up Lloyd, You

Good write up Lloyd, You should have seen the anxiety that a young grad student shown when she gave a short work shop on her findings of doing IR camera pics of aluminum window louvers embedded in the concrete façade of an early LEED certified college dorm. We don’t see them much any more…..

Nice slide show, Lloyd. I don

Nice slide show, Lloyd. I don’t know what you said with each slide, I didn’t see Wilson’s graph in there anyway, so I’m sure it was fine.

First off still not sure how

First off still not sure how this defends the use of HCFCs as a blowing agent. Maybe the manufacturers will start using the new formulation like Solstice but you will not likely find it at your local supplier anytime soon. In no uncertain terms it is rotten stuff for the environment and avoidable. Honeywell make this case in their own charts about the very substantial length in “payback” for their traditional formulas compared to Solstice.

I have never like the idea of having a “payback” as would mean these insulations are not fungible with much better materials for a climate impact POV. My cellulose house performs exactly the same as your SPF house but without the upfront climate hit.

And given that most foams including XPS are 60X or so the embodied energy of cellulose and approximately 10X that of mineral wool per effective R value the climate impact in insulation choices is a big deal.

Allison we are really still going the wrong way in the building industry when it come to the overall building impact, and to get higher performing buildings we have to look at both energy consumption and material climate impact. Some researchers (whom I spoke with in Australia recently) are suggesting we are way under accounting the material impact in building. It’s a chew gum and walk at same time thing.

And then consider this- In the next 15 years, due to a massive building boom, half of the climate impact of buildings will be from the manufacture and installation of materials. No get-out-of-jail-free card for using a little extra foam to ‘save’ energy when you look at the issue at scale.

Less concrete and steel, more wood and other local materials, more density, and foam should be a last resort – not first.

Within the United States

Within the United States existing housing stock is going to be around for a very long time and in many cases foam (Rigid or Spray) is the only way one can adequately address thermal bridging/air intrusion within these structures.

kris, thats so not true! It

kris, thats so not true! It seems (not to be offensive here) an ignorant comment …where is your proof of that? And I suppose I have to come up with a backlash of info for my comment, but all you have to do is study Passive House methods and testing, and that will prove you wrong!

Andrew, everything you’ve

Andrew, everything you’ve said is fine. I have no problem with someone arguing that you shouldn’t use ccSPF or XPS because of the possible use of blowing agents that may be bad for global warming.

What I do have a problem with, though, is Wilson’s attempt to quantify a payback when his calculations were based almost entirely on assumptions. There’s a good reason he didn’t include quantitative uncertainties with his results: They probably would have shown that his results had no scientific significance. Using a different set of assumptions could yield wildly different results.

You’re welcome, Thomas. Yes,

You’re welcome, Thomas. Yes, pointing out the negatives is a good thing. But attempting to quantify something by doing calculations based on assumptions leads to misinformation.

@Robert Haverlock

@Robert Haverlock

Maybe you misunderstood what I’m saying. I’m speaking about existing housing stock that has been built over the last 20-25 years and not likely to be torn down any time soon. In the U.S. the walls of these homes are typically stick built with 2×4’s 16″ OC, fiberglass insulation, house wrap may/may not be there and the siding is nailed directly to the sheathing (no rainscreen).

Retrofitting the typical 1990’s tract built house to PH standards isn’t impossible given enough $$. Anything is possible with enough $$, but in the U.S. it seems that exterior rigid foam board offers the current homeowner the best bang for the buck. Especially in mixed-humid climate.

Allison-

Allison-

Thanks for taking up both of these topics.

First, a dish of calamari has long been one of my favorites and there’s been an approximate 1-in-3 chance the “hogs’ anus” comment is made since that radio program aired. Now, the 1-in-3 is not scientifically verified (this is from memory) but is also from a specific sample of my dining companions (who are probably more likely to listen to This American Life than a random sample of US Residents). So my graph will not necessarily represent total US back-talk and will likely fail a peer review.

I poor digression on this to address your second point: determining some vague ‘payback’ for global warming based upon materials choices. Absolutely Alex Wilson’s graph includes a large set of assumptions. There’s a complimentary chart in the same report which provides the numbers for many of them, from R-per inch to Embodied Energy to the final column which lists GWP per sq.ft.of R. Why I utilize this diagram is to represent the relative impact of ingredients, not to define a specific payback (how can one quantify a payback without including the source of the energy which is being off-set by efficiencies?) Relatively, ccSPF and XPS ingredients have a significantly greater GWP than the competing products. Maybe we should sit down and put together a graph with altered assumptions, but the divergences between the lines will still be large, no?

The word from an insulation colleague is that Honewell’s Solstice blowing agent will be pretty universal for ccSPF by the end of 2017, at least in our region. The XPS manufacturers are slightly cleaning up their act (down to a GWP of ~800) but they still will not follow the lead from European regulations which already have significantly lower numbers.

I think the problem that some

I think the problem that some people are reacting to is that this post gives the impression that you’re saying “nothing to see here, move along folks” to the whole issue. I agree that Alex Wilson’s numbers aren’t particularly useful, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem, and from your follow-up comments I think you agree with me. Unfortunately Alex Wilson seems to be the ONLY one in North America making a stink about this, something which I consider a serious issue. I’d love to have some more reliable data on the GWP of XPS foam. Until I have it, I’ll use the precautionary principle and continue to avoid XPS for projects unless there’s absolutely no alternative.

I’m the type of person who

I’m the type of person who would immediately call BS (and I’m not talking building science) on the calamari issue. I’m also the type of person that is seeking out information to update the information first revealed (in a very professional fashion I might add) by Alex. Yes! He used assumptions. We all do. All of our calcs are based on assumptions! He was also upfront about them which I highly respect and much more than we can say for almost anyone in the foam insulation manufacturing industry.

His main point still holds true: XPS and ccSPF with high-GWP blowing agents have a much longer (and often onerous) GHG payback.

The assumptions needed to quantify this go beyond the GWP of the foam to the aspect ratio and orientation of the particular building, the heating and cooling systems, and the occupancy patterns. His point is well understood by the industry: avoid spray foam until the manufacturers improve the GWP of their product.

Now it’s up to the manufacturers to present clear, verifiable information about what types of materials and improved blowing agents they’re using so the building industry can confidently use their products.