Frost in the Attic Has an Obvious Cause

If you’ve ever seen frost in the attic in winter, it’s pretty to easy to understand why it’s happening. It’s the same thing that causes morning dew on the grass, frost on the exposed half of my car, or water dripping from the bottom of a duct. Condensation requires two things: water vapor in the air and a surface cold enough to entice that water vapor to leave the air.

Look at the nails in the lead photo above or the metal ridge vent below. Those nonporous materials will collect water from the air when they drop below the dew point temperature of the water vapor in the air. Let’s apply these principles to the frosty attic in the first two photos.

The symptom: Moisture in the attic

When it gets cold outdoors, an unconditioned attic gets cold. The roof deck gets cold. The framing gets cold. Everything in the attic gets cold. But cold air is dry air, so if the attic is filled with outdoor air, there shouldn’t be a problem.

A related symptom occurs in some frosty, wet attics. If the roof deck and framing stay wet long enough, mold can start growing there. In many homes, frost in the attic might lead to high heating bills and perhaps reduced material durability. But if you get a serious microbial infestation, your health could suffer, too.

The cause: Air leakage

Many attics have a lot of air leakage, especially in homes built more than ten years ago. In winter, the indoor air will have more humidity than outdoor air. If it leaks into the attic, that raises the dew point temperature of the attic air. And that makes it more likely that water vapor in the attic air will find cold surfaces, creating the kind of condensation and frost you see above.

Houses have A LOT of pathways that let indoor air leak into the attic. The photo above (from a different house) shows an open chase on the right and an unsealed penetration on the left. There are also unsealed wiring penetrations, the unsealed gap on both sides of the top plates, dropped soffits, can lights, and more. And sometimes contractors get really creative with their holes.

The photo above is one of my favorite air leaks. This was in the kitchen of my wife’s parents’ house. As I crawled through the attic of their house, I found an extremely dirty patch of insulation. I pulled it back and looked down through that hole. After a minute of being puzzled, I realized I was looking at the back of the refrigerator. When they had their kitchen redone a decade earlier, the contractor must have thought it would be a good idea to vent the fridge to the attic. Of course, that extra heat from the fridge accelerated the stack effect, sucking a lot of their heated air up into the attic each winter.

By the way, some people believe that houses should be intentionally leaky. You know, a house needs to breathe, right? Wrong!

The solution, part 1: Air sealing

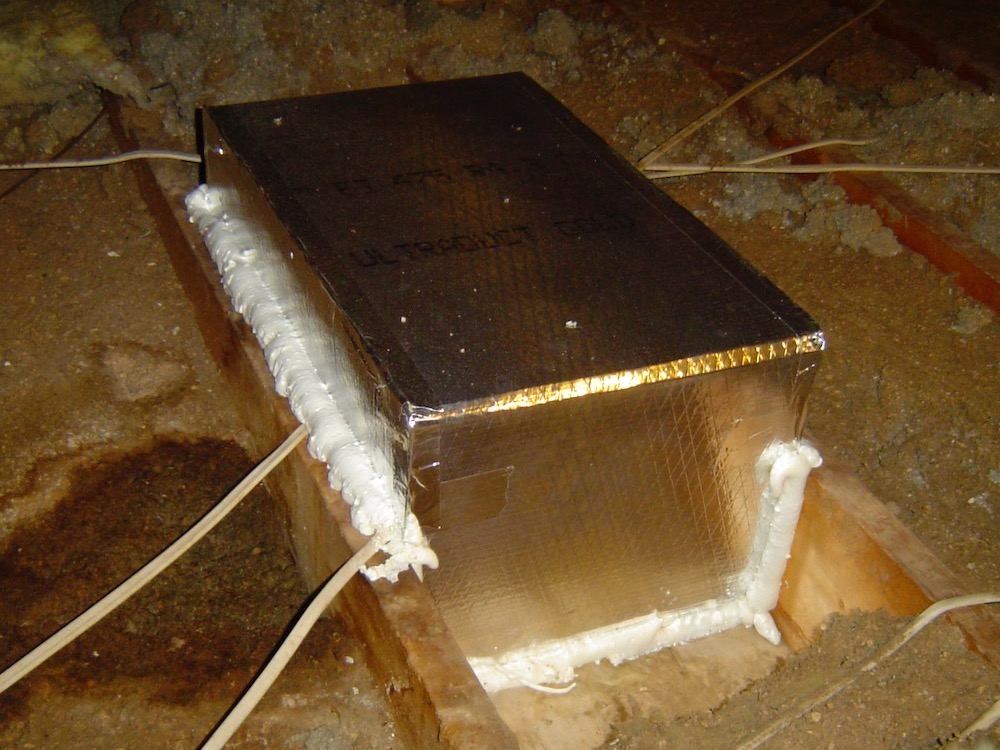

So, the first thing to do is keep the water vapor out of the attic. You want to keep it in your living space anyway because leaky houses tend to be too dry. So get all the holes in the attic floor sealed up. The photo below shows how I sealed a recessed can light with rigid fiberglass and spray foam. You can buy covers that make this job a lot easier.

The gap between each side of the top plate and the ceiling drywall also can leak a lot of air. The gap may be small, but it runs for hundreds of feet throughout the attic. The photo below shows that gap sealed with spray foam along with a sealed wiring penetration.

There’s a lot of really good information available for attic air sealing. Here’s a really nice attic air sealing guide from Building Science Corporation. (Scroll down the page and you’ll find the full pdf download link on the bottom right.) Another really good resource is the Air Sealing and Insulation Key Points document (pdf) that Southface created for the Georgia energy code.

The solution, part 2: Venting the attic with outdoor air

Another way to reduce the likelihood of getting frost in the attic is to vent the attic with outdoor air. Cold air is dry air, so bringing outdoor air in reduces the humidity. That in turn reduces the dew point temperature, making condensation and frost in the attic less likely.

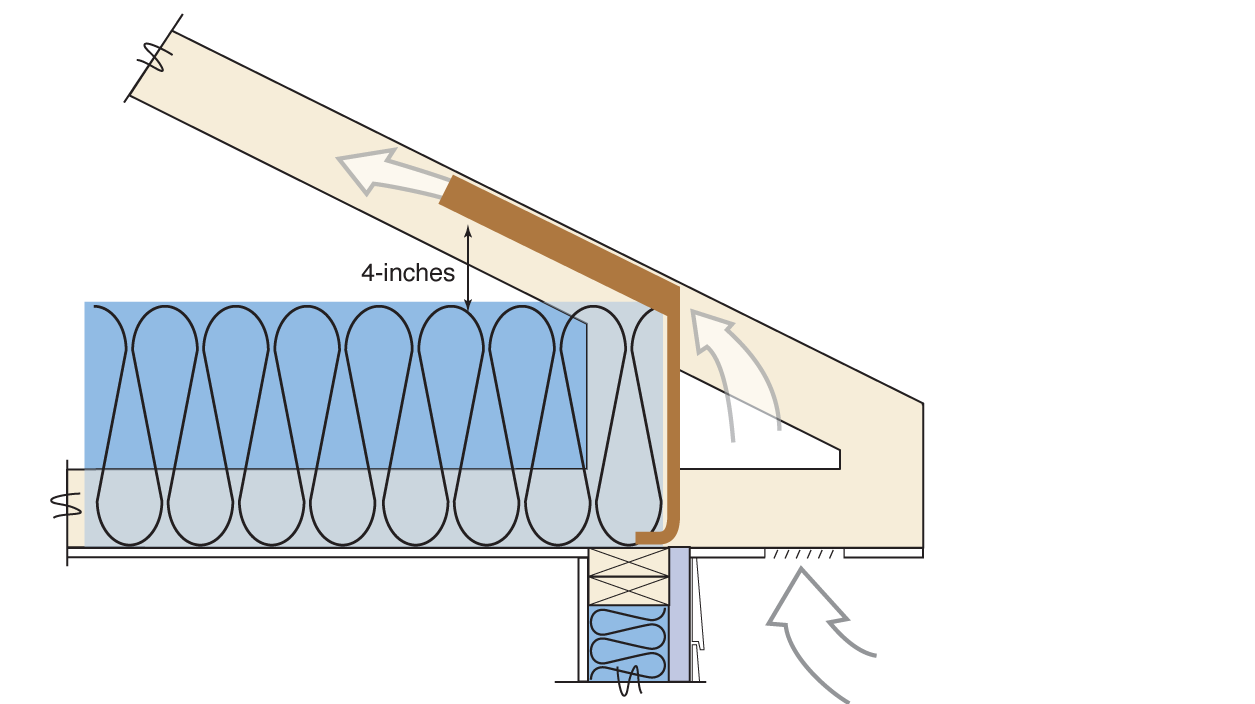

You accomplish all three of those things with a good ventilation baffle, shown in brown above. They’re usually made of cardboard or foam and get stapled in place before insulating. If you’ve already got insulation, you’ll have a lot of fun squeezing into that tight spot to install them. (And by fun I mean torture.)

The photo above shows properly installed ventilation baffles in a home being built. The ventilation channels, of course, must be coupled with soffit vents and ridge vents to allow air to move. When it’s working well, the attic can stay dry enough to prevent condensation and frost. The home pictured at the beginning of the article had a ridge vent and soffit vents, but the insulation blocked the openings near the soffits, so it didn’t get a lot of outdoor air.

The solution, part 3: Encapsulating the attic

Another way to solve the problem of frost in the attic is to encapsulate the attic and turn it into conditioned space. That’s what I’ve got in my house, and it works great. It’s especially helpful if you have any HVAC equipment or ducts in the attic.

By encapsulating the attic, the air in that space will be close to indoor conditions of temperature and humidity, but there won’t be any cold surfaces for water vapor to condense on. You can insulate the roof deck with spray foam insulation on the underside, rigid insulation on top, or a hybrid insulation system.

Buffer spaces like unconditioned attics, crawl spaces, and garages can create a lot of problems in homes. So does the crazy idea that a house needs to breathe. By applying well-known building science principles, we can have eliminate frost in the attic. We can have a more comfortable house. We can have better indoor air quality.

What symptoms do you see in your house?

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

Two Rules for Preventing Humidity Damage

A Tale of Two Roofs – Frost, Snow, and Attic Heat Loss

Two Open Doors to the Attic – A Building Science Nightmare

First three photos of attic frost and condensation courtesy of Todd Abercrombie of Midwest Building Performance in Peoria, Illinois

Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 8 Comments

Comments are closed.

Hi Allison,

Thanks so much for your continued focus on the fundamentals. We can, as a consumer and as an industry make radical improvements in our energy use and carbon generation with these simple (didn’t say easy) exercises.

Abercrombie’s photo with two yellow arrows also shows us the subtle evidence of this with the dust deposits, appearing to marble the fiberglass and powder the blown product. We often see this marbling with on the wrapping of our duct systems, especially returns.

The Habitat, raised heel truss baffling is brilliant. Our local fire marshal urged us to use a fire rated product for this exercise as wind driven embers can get trapped in the cardboard and defeat our other fire proofing steps.

Thanks again

Arthur Beeken

Arthur: Yes, there’s certainly a lot of room for improvement, and making building enclosures more efficient should be done along with electrification. Interesting point about the “marbling.” I’ve seen it a lot and just chalked it up to old, dirty, compressed insulation. (Just to clarify, though, that photo is from a different house, not the one with the frosty attic.)

Good point about attic ventilation in wildfire country. That’s a huge issue now.

rookie carpenter/apprentice. early 1970’s. I’m working with a “one-man carpentry” company. “owner” asks me if i could finish roofing the newly built two car garage. i say sure thing. next morning i get a call around 7am before i leave for work. owner is furious and swearing, screaming, etc. ” i thought you knew how to roof a building. go look at the customers brand new cadillac in his brand new garage. as i enter the garage there are moisture droplets all over his car. I had grabbed the most convenient roofing nails, (2″). they had penetrated the underside of the sheathing and had condensation accumulating on the nails. so it can happen with just a miniscule amount of temperature and moisture differential. had to tear off the new roof and replace at my time and expense. 1-1/2″ nails this time. lesson learned.

Allison, the SPF under the roof deck looks and works great. But I keep asking myself what will happen when the roofing develops a leak? There will be no evidence inside and the sheathing could be destroyed before you learn there is a problem. What am I missing, or is this a problem waiting to happen?

I’d like to hear Allison’s point of view on your question as well Gene. I’ve had that same question asked of me more times than I can recall in the past. I’ve debated with contractors and homeowners regarding the roof leak dilemma.

To be even more specific with the question, closed cell or open cell on the underside of the roof deck? Is closed cell a bad idea on the roof deck as so many claim? That takes Gene’s question to another level. Which do you prefer to see on the underside of the roof deck, and why?

I believe that climate zone and outdoor humidity introduces another variable when deciding which one to use. Dehumidification of the attic is highly recommended in the humid southeast where I am. Especially with open cell. It’s not a vapor barrier. That’s another topic of discussion though. Let’s stick to the roof deck and roof leak debate. Let’s attempt to keep it brief. Not my specialty as you know Allison!

Thanks!

Chris: No, closed-cell foam isn’t a bad idea, not from a building science perspective anyway. Because of the upfront carbon emissions (https://bit.ly/3IsAcHh), though, it’s not great for the atmosphere. For cold climates, closed-cell foam is the way to go if you’re going to use spray foam. Here in the South, open-cell foam works well, but, as you said, you’ve got to have a way to condition the attic to deal with the humidity.

Gene: I’ve seen roof leaks in regular attics that went undetected because the leakage was small enough that it didn’t wet the ceiling. I’ve also slipped on my bathroom floor because of a roof leak. It came through my open-cell spray foam and landed on the floor not far from where the leak was.

The truth is that if the leak is bad enough, you’ll find out about it one way or another. With closed-cell spray foam, the water may come out somewhere farther down the roof. But it’s got to come out somewhere. Regular inspections of your roof, including the gutters, fascia boards, and soffits, is essential no matter where the insulation is. And as I’ve learned with my house (https://bit.ly/3A8UMJ5), the flashing around roof penetrations may not last as long as the shingles.

With all this moisture in the attic what about the pros and cons of different underlayment? I see a lot of newer synthetic underlayment like Titanium UDL. The vapor permeability of the synthetics is almost zero compared to good old vs 30# felt. Couldn’t the synthetic underlayment trap moisture between itself and the sheathing and cause rot? At least felt has a chance of drying outward.