Guest Post: What Causes Ice Dams and Icicles?

Guest post from Nate Adams, founder of Energy Smart Insulation in Mantua, Ohio.

Guest post from Nate Adams, founder of Energy Smart Insulation in Mantua, Ohio.

It’s that time of year again: Two nice sized snowstorms have hit here in northern Ohio now, and icicles are growing. Contractor phones start ringing off the hook in Northern climates with homeowners trying to stop icicles before it rips their gutters off or ruins drywall and window trim. Worrying about these things keeps a fair number of people in Cleveland and Akron up at night.

Every year, I hear from homeowners that they tried to stop icicles and ice dams when they:

- Replaced their roof.

- Upsized their gutters.

- Installed massive amounts of soffit and/or roof ventilation (although this is a part of the equation).

- Added a leaf guard filter of some sort to their gutters (which makes icicles worse).

- Or (Gasp! Horror!) put up roof and gutter heat cables to melt the icicles. This is throwing energy at a problem caused by energy loss, which is a major pet peeve of mine.

STOP THAT!!!

It drives me nuts that contractors promise to stop icicles with a roof, gutters, or heat cables. They just can’t. Only #3 actually touches the root cause of the problem, the rest are window dressing at best, and harmful at worst.

The root cause of icicles is too much heat in the attic. Period.* Stop the heat, stop the icicles.

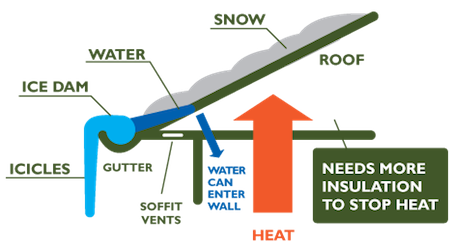

Since we all like pretty pictures (I know I do!) here is one to illustrate:

When you step back and think about it, it makes perfect sense:

- If there is ice in the gutter, snow melted off the roof and refroze in the gutter.

- If the snow melted, there must be heat coming from somewhere.

- If you can stop the heat, the ice should stop too. As I often say, it’s just physics.

So there you go, in theory, fixing icicles is simple. Just stop the heat from getting in the attic or beneath the roof.

As Ron Popeil likes to say: But wait, there’s more.

Stopping the heat from getting into the attic is much trickier than just blowing some insulation in and calling it a day. Don’t let a huckster talk you into a ‘blow and go’ job where they just install insulation and run. That will likely cause future problems like mold, allergy problems, and rot, and may not change your icicles at all.

Instead, let’s dig a little deeper into the building science behind stopping icicles and ice dams.

2 of the 3 types of heat transfer, conduction and convection, are hard at work in your attic during the winter.**

Here are quick definitions, how they apply to your attic, and how to fix them:

1. Conduction is essentially heat transfer through solids. It goes from hot to cold.

Application: Heat from inside your house goes into your attic through the drywall ceiling, roof rafters, chimney, plumbing stack, and so forth.

Solution: More insulation. Insulation is good at stopping conduction, since it slows down heat transfer through the ceiling. The current Department of Energy recommendation in Cleveland (Climate Zone 5) is R-49 up to R-60, or about 16-22″ of insulation depending on the type. Click here to see what the DOE R-value recommendation is in your area.

2. Convection is heat transfer through gases and liquids***. Also goes from hot to cold.

Application: It’s easy to think of heat rising through the ceiling, but there is also a lot of air leaking into your attic around your chimney and plumbing stacks, through the holes where electric lines are going to your attic, recessed lights, electric boxes over lights and fans, the tops of the walls (yep, your walls aren’t that solid after all), and many other spots you would never think about.

The easiest way to think about air leakage is by thinking of a winter coat: if you wear an unzipped North Face jacket outside on a -20 day, will it keep you warm? Of course not, you have to zip it up. Otherwise cold air blows inside the coat and freezes you. That’s what air sealing your house does, it zips the coat of insulation.

Solution: Air sealing. Foam and caulk work wonders here. We have a number of other specialized tools as well. Air leakage is measured with a tool called a blower door. Blower door tests are part of energy audits, check out my post on what an energy audit is.

But wait, there’s still more!

You’ve probably heard that what happens in the laboratory and what happens in the field are 2 different things. That is definitely the case with attic insulation and air sealing.

Air sealing an attic of an existing home is not an exercise in perfection. We find as much as we can, but we are never going to get it all unless I (or one of my brethren) charge more than you want to pay.

That leaves another dilemma. Warm moist air that gets into a cold, insulated attic tends to condense on the roof and turn into mold. (Check out this blog entry to see a real example.) Air leaks let this warm moist air into the attic, and I already said we are not perfect about finding those leaks (nor is anyone else in the industry).

What is a Home Performance contractor to do?

Why ventilate, of course!

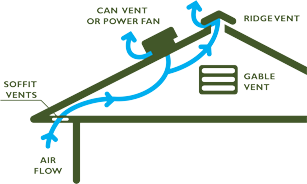

Here is what attic ventilation looks like.****

Attic ventilation makes sure that any excess heat or moisture that still gets into the attic after insulating and air sealing has somewhere to go. The air comes in through the soffits and exits through the top of the roof through can vents (they are known by a ton of other names too) or ridge vents.

So why can’t I just ventilate my attic and call it a day? Because too much heat is in an uninsulated attic for the ventilation to be able to exhaust before the heat melts the snow on the roof and causes icicles and ice dams. So ventilation is important, but vastly secondary to attic insulation and air sealing, in my humble opinion.

Be sure to address attic ventilation as part of any thorough icicle and ice dam reduction plan.

If you have a Cape Cod or bungalow type home that has knee walls, sorry, I don’t have a free guide. I do have a blog post for you, though, that draws more hits than my home page (?!), so it must be pretty good: How to Insulate and Ventilate Knee Wall Attics.

You want to know something funny about this post? All of this information is on my web site as well, plus a good bit more. No one reads it, though, because it’s part of a ‘web site’ and not this newfangled ‘blog’ thing. If you want to dig deeper, click below.

Energy Smart Guide to Icicles and Ice Dams

For even more info, check out the FAQ on ice dams and icicles from Green Homes America, written by my friend Mike Rogers who really knows his stuff. (Are your eyes bugging out yet? They should be!)

Thanks for reading, and feel free to tell me what you think of this article below!

* OK, so nothing in life is really THAT iron clad. Heat in the attic is the majority of the cause of ice damming and icicles, but as my colleague Scott Doyle of Energy Logic pointed out, there are other factors as well. When the sun hits a roof, it warms up and melts the snow below it, then refreezes in the gutter again. So what direction a roof faces and whether it is shaded is another factor in ice damming and icicles. Snow also has R-value on its own, so when it is deep on a roof, it insulates the attic below and holds the little bit of heat a well insulated and air sealed attic holds, and leads to more melted snow. There are other mitigating factors as well. Icicles and ice dams are pretty complicated overall, but the key factor is too much heat getting into the attic.

** Radiant heat (sunlight is the best example) is not a major factor, convection and conduction are.

*** Obviously if heat transfer through liquids is a problem in your attic, call a roofer.

**** Please note that can vents and ridge vents should never be used together, they are only shown together in this diagram to show all common types of attic ventilation in one diagram. Power attic ventilators are frowned upon in the buiding science field, but that is for another post.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

About the Author

Nate Adams owns and runs Energy Smart Insulation in Mantua, Ohio. I met him last year at the Affordable Comfort conference in Baltimore and have gotten to know him a bit since then through our frequent interactions through comments in each others’ blogs, Facebook, and Twitter. He’s an insulation contractor who gets it. As you can tell from this article, he understands and knows how to apply building science. He also gets the marketing thing and social media, as his drive for more Facebook fans last year demonstrates. Promising that he would wear a pink bunny costume for a day if he got a certain number of new likes for the Energy Smart Insulation page, he did and he did, as you can see below. (Just make sure you get out of the way if you see a pink bunny driving a box truck down the road!)

Nate Adams owns and runs Energy Smart Insulation in Mantua, Ohio. I met him last year at the Affordable Comfort conference in Baltimore and have gotten to know him a bit since then through our frequent interactions through comments in each others’ blogs, Facebook, and Twitter. He’s an insulation contractor who gets it. As you can tell from this article, he understands and knows how to apply building science. He also gets the marketing thing and social media, as his drive for more Facebook fans last year demonstrates. Promising that he would wear a pink bunny costume for a day if he got a certain number of new likes for the Energy Smart Insulation page, he did and he did, as you can see below. (Just make sure you get out of the way if you see a pink bunny driving a box truck down the road!)

This Post Has 15 Comments

Comments are closed.

Allison, my bunny suit still

Allison, my bunny suit still can’t top your spot in the Who’s Who of American Women!

I agree with Nate, heat

I agree with Nate, heat cables are a waste of money and a bandaid solution at best. I’d consider powered attic ventilation to be in the same category, but with a couple more issues. First, there is rarely enough intake for the exhauast the fan is providing, so that nice warm air you worked hard to keep in the house is being sucked into the attic. Secondly, it costs money and energy to run when there is a natural method (soffit vents and ridge vents) that works just as well.

I’d also encourage those of us in cold weather climates to include ice and water shield at the eaves when replacing a roof. It may cost a little more, and it certainly isn’t a solution to ice dams, but consider it an extra layer of protection at a vulnerable area when the weather gets really rough.

Adam,

Adam,

Good article describing the fundamentals but I’m surprised there is no mention of keeping ductwork and mechanical systems out of the attic. A band aid approach with some caulk and ventilation isn’t going to fix ice dams if you have a ductopus lurking in your attic.

Good stuff Nate, but I am

Good stuff Nate, but I am going to call you out on the power fan 🙂

I usually find that if a roof system is so complex or poorly built that a power vent is needed encapsulation is a better bet.

I have a small selection of ice/snow pictures here: http://buildingdiagnosticsnh.com/icicles.html

My next website build will have more images and I’m always looking for great ice dam pics, with your credit and link of course. So if any body wants to share let me know.

Lee – Ice guard is always a

Lee – Ice guard is always a good idea here. I do always caution my customers that I will get them a substantial reduction, but not elimination of ice dams.

Skylar – Good point. Furnaces and ductwork in an attic should be a post of its own sometime. You never think of everything in a post, and you can’t include everything either. Thanks for the idea!

Bill – I designed this graphic to show whatever type of ventilation a customer might have on their home, and there are plenty of power fans. I used to like power fans, then I saw the light (or maybe airflow?) Feel free to use the images if you find them helpful. It’s nice being married to a graphic designer!

I would like more

I would like more clarification on how “Warm moist air… gets into a cold, insulated attic”. I think in terms of dew point to measure humidity, and live in the hot-humid South where your normal conditions surely are quite different from mine.

Do you commonly have days where outside dew point is higher than the attic decking? I need some examples of temperature and dew point to understand this. I don’t think it ever happens in S. Texas, not with enough persistence the attic cannot dry out. And I have been told that temperatures below 60-70F were not conducive to mold growth, can you elaborate please.

Mark,

Mark,

Check out Allison’s recent blog on humidity, it should set lightbulbs off for you:

http://energyvanguard.com/blog-building-science-HERS-BPI/bid/57151/A-Humidifier-Is-a-Bandaid-The-Problem-Is-Infiltration

Mark – Good questions! And

Mark – Good questions! And ones that are tough to answer in a comment, they would require a full blog entry, and frankly I’m still learning about that area, so I don’t know it well enough to teach. The article Ted referenced will help with your initial question, check the other stuff Allison has up too.

As far as mold goes, my mold guy told me that 40 and up can be mold growing conditions. If you look at the Wikipedia article on mold growth, it says 32 to 95 degrees for some mold. I expect your knowledge is influenced by your climate zone just as mine is.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mold_growth,_assessment,_and_remediation#Causes_.26_growing_conditions

@Mark, the reference to warm

@Mark, the reference to warm-moist air condensing on underside of roof is referring to interior air (in winter) leaking through the ceiling plane, not outside air.

As for mold, I’m no expert, but I agree with Ted. Mold will grow under a wide range of temperatures, depending on the type. Moisture and food are the primary factors. Also keep in mind that even in a cold climate, the attic will typically rise above freezing during the day. Once mold establishes, daily cycles below its tolerance level won’t kill it.

Another issue is that roof

Another issue is that roof trusses without raised heels can pinch your R-49 attic insulation down to R-15 or worse at the edges. New building codes are now starting to require raised heels but this problem is harder to solve in retrofit applications. Moving to a higher R-Value insulation product at the edges can mitigate the problem, but it’s an expensive fix.

As mentioned, air sealing in

As mentioned, air sealing in the attic is critical. Besides pipe and chimney chases, another big “leaker” is the drilled holes in the top wall plate where electrical lines come up into the attic. Also, the joint between the wallboard and the top plate of walls below the attic, can lights, ceiling registers, bathroom exhaust fans, et. al. The latter must ALWAYS be ducted to the outside, not dumped into the attic.

Since HVAC air handlers in attics are a way of life, they, and the assiciated ductwork, need all joints to be well sealed, and the ducts and plenum need to be insulated, to prevent humidity from condensing in the summer when a/c is running.

I disagree with the condemnation of gable-end power vents, since they are able to draw out attic air which can exceed 140ºF. in the summer, while drawing in exterior air which may be as hot as 90ºF., thus reducing the latent heat load in the attic, and the work load of the air conditioning system. The fan needs to be mounted on a plywood sheet which totally covers the exhaust gable-end vent, but with a round hole the size of the fan shroud cut into the plywood, so as to create a venturi effect for the exhaust air. The adjustable thermostat needs to be at the high point of the attic, so as to maximize the ability of the thermostat to sense when it needs to kick on the fan to remove hot, humid air

Nice job – here is my take on

Nice job – here is my take on the subject: http://youtu.be/MNMD3zI_vbc

Mr. Parker, in close to over

Mr. Parker, in close to over 2000 attics I have been in during the summer with a properly mounted (baffled) thermostatically controlled attic fan I have never seen one that that reduced the interior temperature by more than 8 degrees. And often that drop is assisted by some cool air being drawn out of the conditioned space below.

I’m a great believer in monitoring any situation to determine what is actually happening. In a number of cases I have monitored temperatures in these spaces and checked pressures to determine if the fan is sucking conditioned air out of the house. The only time I have found that air wasn’t being sucked out of the house was with a few newer houses with with one of those big steep pitched hip roofs with a LOT of soffit venting.

Except in those few cases one of these fans sucking air out of the attic is not really helping (remember, you can’t remove radiant heat with air flow) but actually costing the homeowner money, likely reducing comfort and in some cases providing a situation within the building enclosure that results in mold growth. Doing the right thing wrong is always wrong.

W.J.Parker: I fully concur

W.J.Parker: I fully concur with John regarding powered attic ventilators. They not only use more energy than they save but can rob the home of conditioned air.

And if ceiling is air tight (rare) and well insulated, a small reduction in attic temperature isn’t going to have much impact on cooling loads. Think “diminishing returns.”

As John points out, a substantial portion of the ceiling load is radiant, not conducted heat transfer. Conducted transfer is relative to top-of-insulation temperatures, not the temperature at the peak. Although you may see an 8F reduction at the peak, the impact on floor level temperature will be less than half that much.

Not sure what you meant by “reducing latent heat load in the attic.” In summer, latent loads are from exterior air (in winter, the problem is moisture leaking into attic from conditioned space). Increasing attic vent CFM only moves attic closer to outside air dew point. If anything, it will cause higher latent load on equipment to the extent that attic air infiltrates through ceiling when PAV cycles off at night.

If you want to learn more, search Allison’s blog for previous articles that include links to other articles resources on this topic.

Great info! To bad you are

Great info! To bad you are not in PA. Built a house 18 years ago. Installed a new roof this past year. Still ice dams. Living room with cathedral ceiling has dry wall pop open on the exterior/ceiling area and ceiling/dining room joint after every winter. Would love to fix it once and for all.