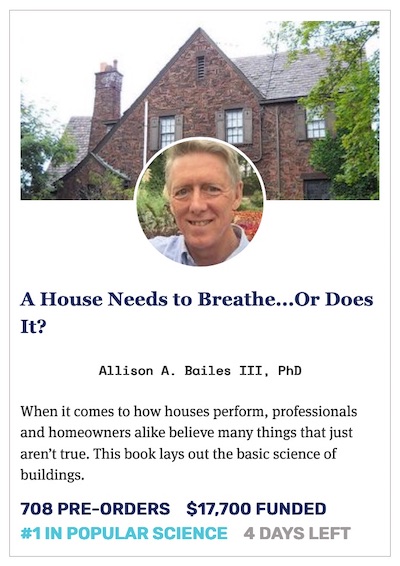

A House Needs to Breathe…Or Does It?

Have you ever lived in a home where you just couldn’t feel warm even though you had the heat cranked way up? How about one where you have to turn up the volume on the TV when the air conditioner or heater comes on? Or a home with a musty smelling basement?

The myths we live by

These and more are problems common to many homes. Whether you rent or own your home, you most likely have suffered with problems of comfort, indoor air quality, noise, high energy bills, and more. The primary cause of these problems is that many of the architects, builders, and contractors responsible for delivering the final product don’t take the full occupant experience into consideration.

And they operate largely based on myths about how buildings actually work. Let exhibit A be the title of the book: “A House Needs to Breathe.” This statement is usually shorthand for, “I don’t believe the cost of air-sealing a home is justified by the benefits.” It’s wrong, though. Random air leaks through the building enclosure don’t work. That photo at the top, for example, allowed a lot of air to move between the house and attic, affecting energy bills, comfort, moisture, and indoor air quality.

A house does NOT need to breathe, but the people inside it do. There’s no level of airtightness that makes a house too tight. If airtight homes have indoor air quality problems, I guarantee you it’s not because they don’t have enough air leaking in from attic, crawl space, or garage. It’s because of too many pollutant sources inside, poor filtration, and inadequate ventilation.

I’m writing a book

The Energy Vanguard Blog turned ten years old last month. In the past decade I’ve published more than 900 articles here, many of them discussing the myths that are so pervasive in the building industry and the ways to overcome those myths. Whether it’s achieving a high level of airtightness, understanding how to get the most out of your insulation, or solving moisture problems, I’ve probably written about it here — and in some cases, I’ve written about it many times.

Now I’m working on a book to put a lot of the most important information in one place. This book will explode the myths, misinformation, and nonsense that pervades the world of home building, remodeling, maintenance, and operation. You’ll get building science principles in plain English so you can understand why those things you’ve been told are wrong and what are the proper ways to make homes comfortable, healthy, and energy efficient.

The good news is that you can pre-order this book now. I’ve been running a crowdfunding campaign on Publishizer to get the attention of publishers. The more pre-orders and funding I get for the book, the more and better publishers will be interested.

But I don’t want you to pre-order the book just to help me. I want you to pre-order the book because you’ll find a lot of value in it. Click the image above (or this link) and read more about the book. Watch the video I made in my spray foam insulated attic. And look at what some people who know have written about this book in advance.

What people are saying

Over the years I have learned so much from Allison’s writing. He has a great talent in making dense topics engaging and relevant. In the field of building science, this is a rarity! If you live in a house, pay utility bills, and are concerned about your health, this book is a must!

~ Amanda Hatherly, Director, EnergySmart Academy at Santa Fe Community College

Dr. Bailes is my favorite writer in building science and HVAC design because of how he simplifies and explains complex topics. This book is sure to be a must read.

~ Bryan Orr, Founder of HVAC School and host of their podcast

Allison Bailes makes the complex world of building science seem intuitive. He combines the penetrating analysis of a physicist with the flowing narrative of a storyteller. And the story he tells is about what your home can and should be doing to make your life better. You’re going to want to read this book!

~ Kristof Irwin, P.E., host of the Building Science Podcast

Please take a look and consider pre-ordering one or more copies. You’ll see the various bonus levels on the right side of the Publishizer campaign page.

But hurry because this campaign ends midday Thursday, 16 April. That’s about 72 hours from now. Here’s that link again:

A House Needs to Breathe…Or Does It?

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and founder of Energy Vanguard. He is also the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard and pre-order his upcoming book at Publishizer.

Related Articles

Myth: A House Needs to Breathe

Winterizing Your Home? Don’t Caulk the Windows!

Flat or Lumpy – How Would You Like Your Insulation?

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 19 Comments

Comments are closed.

I think we were able to get

I think we were able to get by building leaky houses probably up until the late 40s and early 50s when air-conditioning became more prevalent, especially in the warmer, more humid climates. The wide difference in temperatures between outside and inside combined with high dew points was a recipe for disaster. Tighter houses combined with dedicated de-humidification units and powered makeup air helps to make a solution much easier. Keep up the message Allison.

Thomas, the key phrase in

Thomas, the key phrase in your comment is “get by.” Yes, we could get by with leaky houses, as long as we didn’t mind a little discomfort and higher energy bills. But every time we make significant changes to houses like adding insulation to the walls or putting in air conditioning, we make it harder to get by with the old techniques. With modern building enclosures, heating and cooling equipment, and homeowner expections, we’re requiring houses to maintain larger temperature, moisture, and pressure differences. That means we have to give up a lot of the old ways that allowed us to get by.

As you said, we want airtight homes with mechanical equipment that keeps them cool in summer, warm in winter, and the relative humidity in the range of 30% to 60%. And we have the knowledge and materials to do that now.

Thanks for your comment!

What about older homes that

What about older homes that are being restored, rather than wholesale renovated? My house was built in 1930, and has no insulation and the original windows. We pulled the 1950s-era furnace a couple of years ago, and have been heating with the wood-stove in the basement, and we’re constantly battling humidity problems in the winter. Have you any articles that might help chart a good middle course; we really don’t want to gut the house and try to make it modern, but I’m getting tired of scrubbing the walls behind bookshelves as part of spring cleaning. Part of what makes us nervous is understanding that a lot of old houses weren’t nearly as tightly built as new ones, and I’m loath to do something like blow insulation into the wall cavities if water is infiltrating anywhere…

I just watched your short

I just watched your short video promoting your book. One question I had was the use of open cell spray foam on the underside of the roof sheathing in the attic space? Is there any concern the vapor openess of the open cell foam allows inside air to possibly come in contact with the wood sheathing…..i.e. cold sheathing surface in winter coming in contact with warm indoor air? I am asking because I am considering a conditioned attic for a home that I am currently designing and am considering several options for the roof envelope. The home is in climate zone 4, Delaware coast area. Any insite is greatly appreciated. BTW I have been following your blog for many years and did just preorder your book and am looking forward to it! Thanks for all the great info!

Michael, I did briefly talk

Michael, I did briefly talk about the issue of high humidity in the video but of course didn’t have time to go into the details there. Here are a couple of articles I wrote in 2016 about this topic that should cover it in sufficient detail for you.

Humidity in a Spray Foam Attic

High Humidity in a Spray Foam Attic, Part 2

In short, open-cell spray foam is fine in an attice as long as you consider the attic conditioned and do something with the air. What I’m doing with my attic is using an exhaust fan to keep the attic under a slight negative pressure, pulling air up from the living space below. I’ll write about that sometime this summer after I have some hot-weather data.

Question, my two story had

Question, my two story had gable vents, ridge vents but no vents on over hang of the roof. As we live in

North Texas with summer temps of 100 are common. Attic has fiberglass batts with over lay of a white blown loose insulation added. Would adding a attic fan like yours help in cooling the attic temps. Roof deck is not insulated.

John, when you have a vented

John, when you have a vented attic, it’s best not to use any fans to increase the ventilation. Unless you’re spending time in the attic, you don’t need to worry much about how hot it gets up there. You mentioned your attic is insulated. The other important thing you need is air sealing. You want as little air exchange as possible between the living space in your house and the attic.

Here’s an article I wrote way back in 2011 on that topic. As you can see from the 169 comments that came in before comments closed on that article, it’s quite a hot topic.

Don’t Let Your Attic Suck – Power Attic Ventilators Are a Bad Idea

I just missed the pre-order

I just missed the pre-order for your book. Is there a list I can get on for when it is released?

Ian, yes, you can subscribe

Ian, yes, you can subscribe to updates on the campaign page at Publishizer:

A House Needs to Breathe…Or Does It?

I’ll provide occasional updates there about the status of the book, including when it’s going to be available. There should be another window for pre-orders once it’s all done but not yet available.

Will the book be available

Will the book be available for purchase after the pre-order is closed?

Sam, yes, I’ve got to finish

Sam, yes, I’ve got to finish writing the book and then go through the publishing process. My plan is to have it available by the end of 2020. If you subscribe on the Publishizer page for the book (link below), you’ll get all the updates about the status of the book and be alerted when it’s available. You’ll also find out here in the Energy Vanguard Blog.

A House Needs to Breathe…Or Does It?

I have a customer asking

I have a customer asking about an floored attic space that was sprayed with open cell foam and also had blown in cellulose. Someone told him where they touch could create problems? Is this valid?

Ken, there’s nothing wrong

Ken, there’s nothing wrong with touching cellulose or open-cell spray polyurethane foam (SPF) insulation. If you damage the SPF, yes, it can create problems by allowing air leakage and not insulating as well as it should. Likewise, if you disturb the cellulose so it’s not thick enough in some places, you’ll have excess heat flow in that area.

Allison, I am a homeowner in

Allison, I am a homeowner in Columbia, SC, and came across your blog as I was “researching” foam insulation online. My house was built in 2008 in an older, established neighborhood in Columbia. We did not use foam insulation and i wish that we had for both energy and sound purposes. Is it even remotely feasible to consider adding foam insulation in the walls and ceilings now? I think i know the answer to my question but figured i would at least ask an expert.

Thank you!

Jeff

Jeff, sorry for the delayed

Jeff, sorry for the delayed response here. It’s certainly possible to add spray foam insulation to the attic of an existing home, but putting it in the walls usually requires having the walls opened up. There are some foams that can be installed in closed cavities, but you need a really good installer to do that right.

I have a couple of tiny

I have a couple of tiny preparatory questions before I can post the main one. First—what formatting syntax do the comments support: is it Markdown or some custom syntax? If the latter, where is it documented? Second—when does a blog post stop accepting new comments? What if I have a question about an old blog post, e.g. the one titled “What Happens When You Put a Plastic Vapor Barrier in Your Wall?” Of course, I can try to ask it here since the book includes that topic too…

Anton, I’m not an IT guy so I

Anton, I’m not an IT guy so I don’t know the answer to your first question. Which means I don’t know the second either. I can answer the third one, though. We used to have the blog on a different platform and after a while I started closing comments after one year. Most of the comments on earlier articles seemed to be spam, so it made managing that easier. In 2016, we changed to a different platform and since then, all new articles still have comments open. The cutoff for commenting on old articles is probably around 2015.

Feel free to ask your question here.

Actually yes a house needs to

Actually yes a house needs to breathe.

The trend towards air tight homes is killing people.

Covid merely exposed this danger to the world.

A tightly sealed home has a very toxic atmosphere if you do not bring in outside air and fully exchange the indoor air many times per hour.

The greater the percentage of outside air the healthier the atmosphere in the home.

This is why all new home building code require outside air intakes

just like the air handlers that have been used in commercial buildings for decades.

This doesn’t set well with many save the planet types but facts are facts.

EVERY home should have outside air intakes tied directly into the HVAC system and windows should be kept open whenever possible

Jim, your information is

Jim, your information is seriously out of date. So tell me, how does it improve the indoor air quality to allow musty, moldy air from the crawl space to come in through random leaks that should have been sealed? How many people have been made more healthy by breathing gasoline fumes, car exhaust, and pesticides from the garage? How does extra dirt in the air that got sucked through that dead squirrel in the attic help anyone breathe better? The answers are (i) it doesn’t, (ii) zero, and (iii) it doesn’t.

Now, you almost had the right answer when you said “if you do not bring in outside air.” But then you went and prescribed massive overventilation. To “fully exchange the indoor air many times per hour” would be ridiculously expensive for homeowners, either in buying a lot more mechanical equipment than they really need (and paying the energy bills) or in creating new indoor air quality and health problems by losing control of humidity and temperature. That’s a recipe for mold.

Your knowledge of residential building codes isn’t accurate either. You wrote that “all new home building code require outside air intakes,” and that’s simply not true. Yes, the model codes have requirements for mechanical ventilation, and they’re tied to the infiltration rate of the house. In some places, meeting the air leakage code requirement means you’re also required to put in ventilation, but not everywhere. And there’s the actual codes as adopted by states and local jurisdictions. Here in Georgia, for example, new homes must test below 5 ACH50 but they don’t need ventilation unless they’re below 3 ACH50. I agree with you, though, that all new homes should be airtight enough to be required to have mechancial ventilation. Ventilation rates haven’t been specified in air changes per hour for a long time now, but the current rates in the code would come out as a few tenths of an air change per hour and not anywhere near the “many” air changes you suggest.

But airtightness and whole-house mechanical ventilation are only one aspect of good indoor air quality. Local ventilation, especially with the kitchen range hood, is really important. Filtration with high-MERV filters helps tremendously, especially with PM2.5. And above all, source control keeps bad stuff out from the beginning.

Now, you’re in luck, Jim, because I’m writing a book this topic, and it’ll be out next year. Click the banner at the top of this page to subscribe to updates, and you’ll be one of the first to know when it’s available.