What Is the Relative Humidity When It’s Raining?

Serious question here. Have you ever thought about what the relative humidity is when it’s raining? I’ve heard people say it’s 100% because, well…because it has to be. It’s raining, dammit! What else could it be?

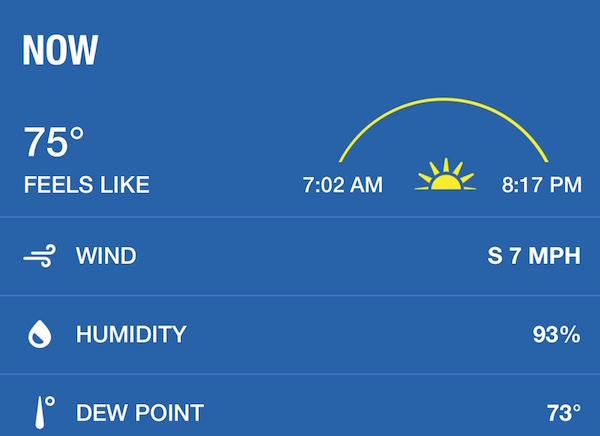

Not so fast there. This is something we can actually look up on a weather app or measure with a hygrometer. In fact, it’s been raining here at my condo this evening so I looked at my weather app and saw this:

There. The relative humidity was 93% while it was raining. So it doesn’t have to be 100% when it’s raining after all.

The reason has to do with evaporation and condensation. When a surface of water (which could be a raindrop) is in contact with open space (which could be filled with air or some other gas or a vacuum), water molecules will be going both ways. Some will be evaporating from the liquid and becoming vapor. Others will be going from the vapor phase into the liquid.

The amount of water vapor in the space is determined by the temperature. If the raindrop is cold, it may actually dehumidify the air it passes through as it sucks up more water molecules from the vapor phase than it releases from the liquid. If a mass of warm humid air has a lot of cold raindrops passing through, the humidity could go down while it’s raining.

Who knew!? Well, Bob Dylan sang about it in his song A Cold Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, so he must have known.†

I’m a-goin’ back out ‘fore the rain starts a-fallin’

Where the surfaces o’ raindrops parch the air of its water

And it’s a cold, it’s a cold, it’s a cold, and it’s a cold

It’s a cold rain’s a-gonna fall

This topic came up at Building Science Summer Camp a couple of weeks ago when Professor John Straube was speaking about moisture physics. He was going to gloss over what happens there but Nerd 1, Ray Moore, wouldn’t let him so the two of them explained how it doesn’t have to be 100% relative humidity when it’s raining and how water can act as a dehumidifier. (By the way, here’s my article about Straube’s presentation.)

Now you know. The air may be saturated with raindrops but that doesn’t mean the space between the raindrops is saturated with water vapor. I expect you to check on the relative humidity next time it’s raining where you are and see if you can confirm what I’ve just said.

Footnote

† Well, OK, I may have doctored those lyrics just a little bit.

Related Articles

Make Dew Point Your Friend for Humidity

The Problem with Relative Humidity

4 Ways Moisture Enters a Vented Crawl Space

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 15 Comments

Comments are closed.

Every now and then I run

Every now and then I run across or hear of an over-the-top house with a significant indoor water feature, and my first reaction is always to wonder how much additional latent load such a feature adds.

Then I wonder how a water feature might perform if its water were to be chilled? Could it remove water from ambient air?

Has anyone done this?

I was wondering that, too,

I was wondering that, too, Curt. And then Peter Kidd gave us the answer: Yes, Manitoba Hydro has done it.

Manitoba Hydro’s office uses

Manitoba Hydro’s office uses water features to humidify / dehumidify building air – large spillway like structures in the lobby, tall artsy (floor to ceiling mylar ribbons with trickling water) in the three 6 storey atriums where ventilation air is introduced (and conditioned) into the building. People see and hear the “features”, most don’t seem to really believe exactly what your article is talking about 🙂

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manitoba_Hydro_Place

Thanks, Peter! But after

Thanks, Peter! But after seeing a presentation at Building Science Summer Camp on Legionella, I’m wondering how safe it is to have a “several 24 meter waterfalls” indoors. The speaker, Jack Springston, discussed how common it is in places where water is sprayed out into the air like that, including in showers. You can download his presentation here:

Legionalla, by John P. Springston (pdf)

https://buildingscience.com/sites/default/files/legionella_jack_springston.pdf

I’m Civil not Mechanical, so

I’m Civil not Mechanical, so I’ll just say the water “features” have been operating for over a decade now. I do recall there was some initial tweaking of the lobby waterfalls (a hydroelectric utility’s lobby, these are spillway analogues, two, about 10 m wide, 5 m high). The 24m tall features are not waterfalls exactly, but water trickling down mylar ribbons within six storey atriums into which the 18 storey building’s tower ventilation air is introduced on its way to an undefloor distribution system. It’s 100% fresh air, passthrough ventilation. One could see lots of opportunity for legionella in the past decade. John Straube has been in the building and provided an absorbing critique of its double wall exterior, but I do not recall him commenting on the ventilation system 🙂

Your “cold rain” (and

Your “cold rain” (and Manitoba Hydro’s office water feature)reminds me of the young Willis Carrier’s 1906 patent, “An Apparatus for Treating Air,” (https://patents.google.com/patent/US808897A/en) which employed a spray of water as a condensing surface. By driving humid air through the water spray, Carrier could dry the air; and by adjusting the temperature of the water spray, he could dial in the air’s humidity. This became the basis for a new line of industrial “air washers” sold by The Buffalo Forge Company in the years just before WWI and the launch of the Carrier Engineering Corp.

Thank you, Clay! I wanted to

Thank you, Clay! I wanted to put that in the article but couldn’t find anything about it online. (I wasn’t very patient in my search.)

Ahhhh, I’ve wondered about

Ahhhh, I’ve wondered about that for years. I might need to read your article a couple more times before it makes sense in my head though. Thanks for writing about this!

You’re welcome, Mark. It’s

You’re welcome, Mark. It’s one of those things that seems obvious…until you really start thinking about it.

Here’s another way to think

Here’s another way to think about this. Rain falls because the air reaches saturation in a rain producing cloud. Once water is released as rain, gravity pulls it to the ground (unless there’s an updraft that blows it higher up where it could freeze into hail)

The point I’m trying to make is that rain is produced when the air (cloud) reaches saturation, but once released, the rain will then pass through whatever air happens to be between the cloud and the ground.

The dryer the air the rain passes through, the more likely it will fully evaporate before reaching the ground, as often happens in arid climates. But in general, there’s no requirement that the air through which the rain passes must also be at saturation. In fact, the local RH could be significantly lower than the 93% in Allison’s example.

BTW, when the air near the ground is at or near saturation, then what we get is fog. What happens inside a cloud is above my pay grade 🙂

Good points, David. Also,

Good points, David. Also, from what I understand, those conditions in the cloud can be significantly higher than saturation before nucleation of water droplets occurs. The vapor pressure can keep increasing until nucleation sites appear.

And yes, the ground RH can be significantly lower than the 93% I showed. Last night it was raining again and I saw on my weather app that the RH was 75%. Here are the screenshots:

[[{“fid”:”2408″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Rain in Tucker, Georgia”},”link_text”:null,”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Rain in Tucker, Georgia”}},”attributes”:{“alt”:”Rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”title”:”Rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”height”:”268″,”width”:”450″,”class”:”media-element file-default”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

[[{“fid”:”2409″,”view_mode”:”default”,”fields”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”75% relative humidity during the rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”75% relative humidity during the rain in Tucker, Georgia”},”link_text”:null,”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“2”:{“format”:”default”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”75% relative humidity during the rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”75% relative humidity during the rain in Tucker, Georgia”}},”attributes”:{“alt”:”75% relative humidity during the rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”title”:”75% relative humidity during the rain in Tucker, Georgia”,”height”:”519″,”width”:”450″,”class”:”media-element file-default”,”data-delta”:”2″}}]]

Note in this second example

Note in this second example from Allison, the actual air temperature is 80 F, it is raining, and the relative humidity is 75%. This means that the raindrops are at or below the dewpoint temperature of 71 F. This all makes sense. But the “Feels Like” temperature is 84 F which is higher than the air temperature. Why? Because it is calculated based on humidity which is still relatively high. Do you think that if you were standing in that rain you would feel warmer than the actual air temperature? I bet that it would “Feel” cooler.

Oh where have you been, our

Oh where have you been, our dew-eyed son? 😉

I’m intrigued by the notion

I’m intrigued by the notion that its the ‘space’ not the ‘air’ that water vapor exists in. You even mention a vacuum. And you say it’s the temperature that dictates the amount of water vapor in a space. I get that the air is not ‘absorbing vapor’ like a sponge, but surely its more than just temperature. The presence of air (or other gas) must take up usable real estate, does it not? This would explain why water boils more readily at lower pressures. Could we say, the vapor is competing for space with the air.

Back on point to this entry: I also note that after summer rains, the humidity seems to drop. I always thought it was a drier air mass ‘moving in’ but could just be the dehumidifying effect of the rain itself. Thanks for the great blog.

My thoughts are

My thoughts are

For rain to fall up there in the clouds where rain forms the humudity would surely have to be 100% (for it to escape)

If you measure humudity Down on the ground it need not be and could be any humidity when the rain is falling