Will Your Water Heater Give You Legionnaires’ Disease?

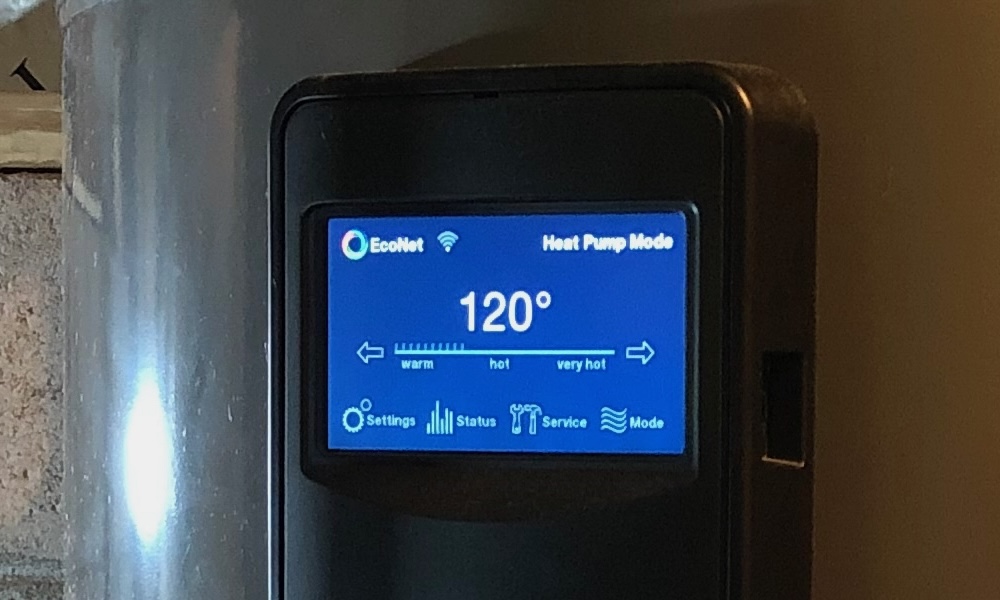

Whenever I post a photo of the control panel of my heat pump water heater (like the one above), I usually hear from at least one reader who has concerns about Legionnaires’ disease. I care about my health, so I’ve dug into this topic a little bit and have made a decision about whether to keep my water heater set at 120 °F or set it higher. I’m no expert here, though, so please let me know what you think in the comments below.

The basics of Legionnaires’ disease

We know a whole lot about Legionnaires’ disease now that wasn’t known in 1976 when 221 attendees at the American Legion convention came down with a mysterious illness. Thirty-four of them died, setting off a furious search for the reason. The culprit turned out to be bacteria that hadn’t been known about before. Its name came from the circumstances of its discovery: Legionella pneumophila.

Legionella grows in fresh water at temperatures between 68 °F and 120 °F. It can be part of biofilms, the slimy stuff growing in a lot wet places (like the inside of a dryer vent in the photo below). You can find biofilms with Legionella in cooling towers, shower heads, misters, humidifiers, and ornamental water features. The biofilm and its Legionella population itself isn’t the problem, though.

The way a person gets Legionnaires’ disease is by inhaling aerosolized bits of Legionella. The lungs then get infected and cause symptoms similar to those of pneumonia. Since it’s a bacterial infection, doctors treat it with antibiotics.

You can find more information on Legionnaires’ disease at the CDC, Wikipedia, and many other sources. ASHRAE has a standard, a guideline, and articles (pdf) on this topic, too.

The effect of water temperature on Legionella growth

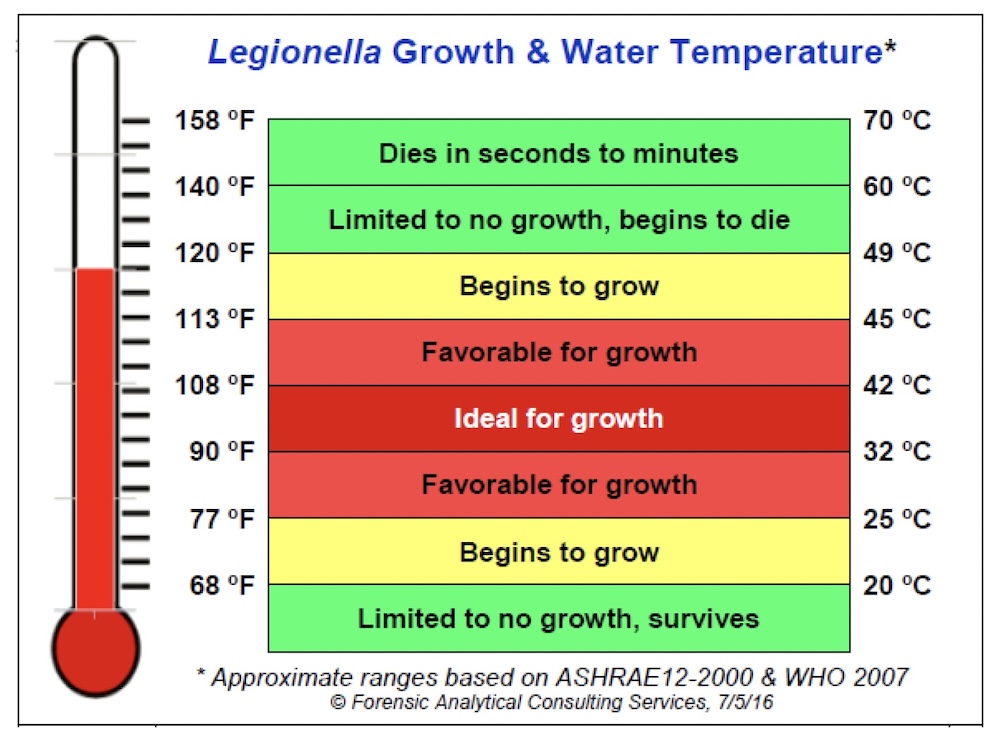

Back to the original focus here, let’s look at how temperature affects the growth of Legionella. The table below is from a presentation that John Springston gave on this topic (pdf) at the 2018 Building Science Summer Camp.

Clearly, you want to stay away from water heater settings between 77 °F and 113 °F, the red regions in that chart. And the yellow regions, too. Above 120 °F, though, there’s not much growth and even some die-off of Legionella. So what’s a person to do?

My current position

I still have my water heater set to 120 °F. According to what I’ve read about ASHRAE’s recommendation, they say the hot water in your tank should be 140 °F or higher and that your plumbing system should deliver hot water at 124 °F or higher. ASHRAE mostly deals with commercial and institutional buildings, though, so does this apply only to those larger buildings? Or to homes, too?

I’m storing it at 120 °F and delivering it at an even lower temperature. Am I doing the wrong thing? I’m eager to learn more from health experts and will set it higher if necessary.

From what I’ve read, it seems that domestic hot water isn’t where most cases of Legionnaires’ disease come from. It’s chillers and hot tubs and water features that aerosolize Legionella particles.

And there’s another reason I feel it’s not such a big a risk in my hot water system. Water heater manufacturers recommend setting the temperature to 120 °F.

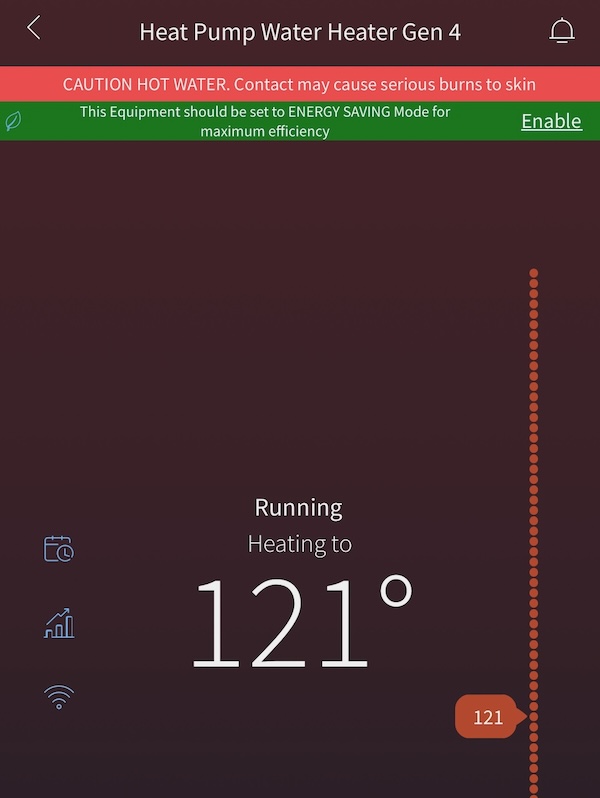

Lawyers are good at finding liability, yet manufacturers don’t warn you about Legionella with that setting. They do, however, warn you about the risk of scalding if you set it higher. The screenshot above shows what happens when I go even a measly one degree above 120 °F.

That’s certainly not a guarantee of a risk-free decision. It just means the risk is too small for lawyers to have changed the behavior of manufacturers…or that they haven’t found the connection yet. In general, though, the number of Legionnaires’ cases is pretty small.

What temperature is your water heater set at?

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can subscribe to Energy Vanguard’s weekly newsletter and follow him on LinkedIn.

Related Articles

Living With a Heat Pump Water Heater

A Layered Approach to Indoor Air Quality

The 3 Types of Energy Efficiency Losses in Water Heating

Comments are welcome and moderated. Your comment will appear below after approval.

This Post Has 57 Comments

Comments are closed.

When I had a tankless electric, there was simply an analog knob. It almost never delivered above 90 (cranking it to the high end sometimes did, but also increased the chances of cold water sandwich). When it was replaced with a tanked electric, I never found a setting, but I have checked it coming out of a bathtub at up to 122.

I thought the risk was highest in standing water, so you’re most likely to have an issue right after your house has been empty for days.

Since I can program my Rheem HPWH, I cycle it to 140 degrees each day for a period of time. During times of little or no demand, it sits at 110 degrees. Normal demand times are at 120 degrees,

I have a solar thermal with storage tank that feeds an instantaneous gas tankless set at ~115F. Never had a problem so far but useful to know I’m living at knife’s edge! I don’t think this is that much of a residential concern and I always recommend 120F to others. Recently got slightly scalded at M-in-L’s house due to someone having set the temperature too high (I reset it to normal point). I think scalding is a much greater risk – stick with 120F.

I have mine set at 135°F (also gives me more to dilute and/or have a smaller tank) and have a mixing valve to keep it all below 125°F to points of use. Also my system is also copper which is naturally resistant to bacteria growth. Bundling of hot and cold can be a source of pipes at the wrong temperature. Dead-legs can also create problems and part of why they are all required to be flushable per current code. I do not think this goes far enough, but dead-legs are only just beginning to be seen as problematic.

I believe that this speaks volumes to why on-demand boilers are an advantage!

I see a couple of issues with residential water heaters that lead me to believe that they are not a problem at 120 F. One is that it takes time for the bacteria to grow and if you are using hot water every day, it probably keeps the tank flushed before any sources can grow. Secondly, what is the source for the bacteria? Hopefully your water supplier, whether it is a utility or your own well, is not a significant source of the bacteria. Thirdly, does you water utility chlorinate the water and does that kill this bacteria? Keep in mind that commercial cooling towers, where this was originally found, recirculate the same water (with some make-up need due to evaporation) and are at the exact optimal growth conditions as shown in this article. So I suggest keeping your water heater at 120 F, especially if it is a heat-pump water and has sufficient tank size and recovery time to meet demand.

We have two water heaters, one that serves the master and half bath and a second that serves the laundry, kitchen and other bathroom. Since there is only two of us we have the first set to 120 degrees and the second set to 140 as we virtually never use the other bathroom shower. We are in our seventies so long ago learned how to avoid scalding but have the first set to 120 to be economical and allow the water heater to last longer. I think that legionaires disease is way down on my list or risks. There are plenty of other things to be concerned about.

The thermostats for the upper and lower elements of electric water heaters are notoriously inaccurate and crude devices. The heaters come from the factory set at 120 degrees and the buyer can reset it. However, NC State Code say for resorts and motels it cannot be set higher than 120 degrees due to scalding danger; it is ok if the hot water system thermostat was accurate for the temperature at the shower and sink faucets. I have had lukewarm showers and baths at resorts. I set my thermostats at 140 degrees, the upper thermostat turns on at 117 degrees and shuts off at 133 degrees to send power to the lower thermostat which turns on, heats and shuts off at 125 degrees. The setting is off by 23 degrees and “dead zone” is 17 degrees. I have changed thermostats with similar results. States should not regulate Thermostat settings unless a new generation of more accurate thermostats become available.

Great post. I have a colleague who got Legionnaire’s several years ago in the South and traced it to a hotel room with wet carpet in front of the AC…probably a different BS problem! In any case, I thought you were going to say you are ok with keeping the setting at 120 degrees since you’re not aerosolizing your water. Separate from the hot water system, what do you think about the risk of a central air system with a humidifier nozzle? Seems it could be a vector for the bacteria to grow and be distributed through the air. If the water is cold enough (i.e. in the winter when it’s used, perhaps it’s below the temperature threshold for concern).

I had a client who had a second home nearby that was used only occasionally – generally holidays because the house was close to family. For several years, she got pneumonia shortly after visiting the house and relatives. It was treated successfully with antibiotics. It wasn’t until this happened several times that her doctor took a culture and found that it was Legionella. We eventually tracked it to the old drum-style humidifier in the heating system. There was no A/C so this was a winter-only problem that made it that much tougher to identify the house as a source. So yes, central humidifiers can be an issue. With the crud I see around the mist/nozzle type humidifiers, I’ve got to think they would be just about ideal for growing Legionella if there is any around.

A mixing valve is required in many jurisdictions and is always a good idea for scald protection. This allows storing water at 140F and delivering it a reduced mixed temperature

Yup, that’s exactly how I approach it in conversations with my clients. That way you have the best of both worlds: Kill the bacteria and have safe water temperatures at plumbing fixtures.

Phil White and Chris Radziminski’s report to Vancouver City Council that you can find here; https://council.vancouver.ca/20200610/documents/cfsc1.pdf ,is super informative regarding the history and growth in Legionella outbreaks in North America.

The water heater is set to 130F; the thermostatic control for the DHW recirculation system is set to 120F. The hot water tank also supplies heat to the house where the Taco XPB heat exchanger for the Warmboard system is on an OTDR from 80F to 95F. (Currently using a boiler, with the replacement strategy being an Air-To-Water Heat Pump). Keeping the temperature below 130F allows the boiler to condense-so it starts to approach the 95% AFUE.

Once a year (fall), the recirculation system is turned up to 130F and hot water circulates through all the faucets for 15-20 minutes.

The 140F is most likely set by lawyers – to limit the manufacturer’s liability. I don’t see a problem with 120F if you flush your system once a year. Schedule any time after the COP for 130F is over 3.0….

As usual, another great and timely article! To answer the question I have chosen 125 degrees for my sealed combustion, modulating, condensing, storage tank water heater. But I have also included a tempering valve as a safety to prevent scalding. Part of my decision was driven by the dishwasher. Many of them no longer use a heating element. So you don’t have a way to boost the temperature of the delivered water. Second, units like this are relying on stored heat from the dishes and dishwasher cabinet to provide the heat for drying.

My water heater is at 120 degrees, as recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics. I am a pediatrician, and that is my recommendation to my patients. I have had sometimes heated (pun intended) discussions online with plumbers who argue that water heaters should be set to 140 due to Legionella. As you stated, the risk of 120, while real, is minimal in residential settings. The only way I would set the water heater to 140 is if the temperature at all outlets was limited to 120. I have seen too many scald burns in my career. Limiting to 120 makes those much less likely.

John

Not an expert.

I keep mine in the 130 range. High enough to be safely in the “legionella slowly dies” range (and to buffer any inaccuracy in the water heater’s temperature reading), but not so high that the risk of scalding is meaningfully higher than it would be if I kept the temp at 120.

As a bonus, my hot water lasts a little longer as well.

I’m in favor of keeping water heater temperature as low as possible consistent with bathing comfort, so 115 – 120*F is my preference. I too have encountered advice to set it higher to minimize risk of Legionella.

I agree with Allison’s analysis here. Let me also add that water sitting in hot water lines immediately following hot water usage likely spends plenty of time at temperatures in the yellow and red zones set forth above as the water lines cool to ambient temperature. The fact that domestic hot water systems aren’t responsible for widespread Legionnaires’ disease suggests this isn’t a problem.

If it were, codes would no doubt require both high water heater temperature setpoints AND continuous 24/7 domestic hot water circulation – they do not. That supports the hypothesis that danger lies not in the temperature but in aerosolization.

As to aerosolization of biofilms from plumbing fixtures, the most risk would seem to be showering – I think it safe to say that biofilms grow on and within domestic showerheads, (confirm for yourself by diassassembling one that hasn’t been cleaned in awhile)and presumably some of that is fragmented and blown into the show enclosure the moment one opens a shower water valve. Depending on the specifics of the hot water system and also bather behavior, it is at least some seconds, if not minutes, between opening the valve and stepping into the enclosure to shower. Again, since this routine daily behavior is not reportedly linked to Legionnaire’s disease, it seems safe.

Setting water heater temperature no higher than necessary for comfort pays a bonus with respect to heat pump water heaters – the lower they are set, the more efficiently they operate owing to the physics of the vapor compression refrigeration cycle that transfers heat to the water.

Hi, This is a fun topic! I’ve played with thousands of water heaters and had to suggest stored water temperatures to clients. I landed on 130F as a good temp because it takes six seconds to get burned at that temp, which gives most people time to move away, and 131F has been considered the temp at which Legionella no longer grows. Getting the right balance between scalding and bacterial infection is clearly still a problem plumbers have to deal with. Setting the right temp is difficult because most water heater thermostats have no degree settings and are usually accurate to within about twenty degrees… Then there is the oversized plumbing we all have. Fixture flow rates have been going down for many decades and pipe sizing has remained mostly the same. We create opportunities for biofilm and bacterial growth with our plumbing systems. I read somewhere that the number of known cases of Legionnaires have roughly tripled in recent years. Appendix M in the plumbing code is a good step in the right direction. I look forward to the day we can use right-sized piping or tubing. To answer your question, I try to keep my delivered water temp at 130F, but have found the water temp varies as the air temp in the room where the water heater is varies. This is a control problem. Anyway, much to chew on, nice article!

Yours, Larry

I know almost nothing about Legionella, but having read that it can survive at 120, I set my water heater to 130. Your lawyer argument is a reasonable heuristic. But I have seen lawsuits brought both for doing something and not doing the same thing.

I would be happy to learn that 120 is a safe, healthy setting.

Do you recommend a shower head with a Legionella filter?

This is timely as I just installed a heatpump water heater two weeks ago. The > 120° scald warning is on the app and the machine. We tried 120° and found it woefully lacking. There’s a long run between the water heater and the 2nd floor bathroom and to take a shower with the 120° setting, it was the hot wide open and the cold off and the shower barely tolerable. After experimenting, we ended up setting the temperature at °140 as hot as it would go. We enjoy a fancy double shower with three shower heads and there’s simply more flow with the hot turned up because you’re using less hot and more cold. You also don’t drain the tank as fast because you’re using less hot water in total for the same showering time. That should make the heater run less which should save energy, but that might be offset by heating to a higher temperature. There’s actually a mixing valve sold as an energy saving device that mixes cold with 140° hot right at the tank. I’m basically doing the same at the shower valve. We have a 65 gallon Rheem hybrid.

Galen, I have a similar but probably worse problem since the long run hot water pipe is uninsulated and runs under the slab through wet soil and ground water that cool the pipes in a minute. I have to keep the shower running as I soap and scrub, if not have to wait another 4 minutes and waste 4 gallons of water before it warms up again.

Stanley, I just replumbed the whole house except the risers to the 2nd floor bathroom, so I was able to insulate the hot line in the basement. Roughly 20 feet in the walls is uninsulated.

I’ve had this come up a few times, and from my research, Legionnaires is much more likely to live/develop on shower heads.

Other water temperatures (trivia). The Sous Vide is set to 124.5F for cooking beef to medium rare; the hot tub is set to 98F (even in -22F) which is comfortable in winter. Which brings me to the question is this objective (quantifiable) or subjective (a feeling).

From my work background on a chemical waste incinerator; we shutdown the process when Legionella was found in the cooling coils.

It just means the risk is too small for lawyers to have changed the behavior of manufacturers…or that they haven’t found the connection yet. That’s what happens to digital water heater monitor + or -4°F deferential

Many years ago in a bachelor rental I discovered that the gas pilot alone would heat enough for dishes and shower. My first energy savings project. No legionaires happened.

That dryer hose photo got me. Won’t be able to sleep tonight thinking of all the times I walked through dryer plumes. Then there’s the maintenance I’ve been neglecting…

And what about faucet aerators, water fountains, spray bottles for the beach and that new patio mister I got last summer, and my next trip to see the geysers at Yellowstone National Park?

I did a little digging and found “Legionella water filters” are a common component for evaporative cooler safety. In southern Arizona, I measured 95F at the kitchen cold water tap.

I have been thinking about the lawyer argument. Clearly the lawyers think the scald risk is higher than the bacteria risk. But that might not directly translate to the risk to the occupant. Perhaps it just a much simpler risk to identify and therefore easier to find a clear nexus to the the water heater manufacturer. In the case of the legionella (or other bacterial disease), you would first need to recognize the disease; then prove that it came from your hot water system and finally that it was cased by the the water heater before you can get to the manufacturer.

I crank up the heat in the tank (150 degrees or more) and use a thermostatic mixing valve to mix in cold water that arrives to the faucet at exactly 120 degrees. I have a natural gas water heater. It’s the only natural gas appliance used in the summer and my summer gas bill is <$10. I'm not considering the cost of potentially degrading the tank faster by keeping it at a higher temp.

When I eventually switch to a heat pump water heater, I'll do some calculations about the electricity cost of warming past 120 degrees and also analyze tank size needed due to the increase in water volume from the injection of cold water into the hot supply. My hope is I can get away with the 120v water heater.

Great topic and something I have wondered about but for a different reason. In the summer here in Crematoria our incoming cold water supply will be 80-85*… So it’s something I think about as well but on the “cold” supply side. Now if ours is that warm I’d hate to see how hot it is in places like Vegas.

And if anyone has any realistic ideas of how to cool down the incoming water supply so I can actually have cold water at the tap. Oh and when taking a shower in the summer you start off using a little hot water then you slowly turn it to all cold and it’s still too warm to get a nice cool off in the summer. Our ground temp is pretty high in the summer and I also have a well for irrigation and the water is 73* coming out of a 100′ deep well.

You can keep your tank at 140F and install an anti-scold device (mixing valve) on the tank outlet piping set to deliver 120 to your taps ect. This is standard practice in Canada. Also provides more ‘hot’ storage since there is more hot water store at the higher temperature then is being delivered to the house. The way it works its a 3 way valve – you tee the cold going into the tank into one side of the valve, the hot 140F water out into the other side and the mix temp comes out at between 90 and 120 depending on where you set it. Problem solved.

The higher the setpoint the lower your efficiency

Gas in particular can see significantly higher efficiencies below 130f

I don’t worry about my water heater which averages 117° supply temperature. I have some concerns about my central humidifier which is of the evaporative type . I measure reservoir temperatures at around 80-85° . I add antibacterial treatment periodically to it as a precaution..

I have a 65 gallon Rheem HPWH, it delivers water at 116F (verified by 4 different sensors) when the temp is set at 120F so I set it at 125F to compensate for the apparent inaccurate internal sensor.

To get the local utility HPWH incentives ($600 – $800 for the HPWH and up to $1,200 for electric service upgrade) they require a mixing valve recommend set at 120F and recommend tank temperature at 130F – 140F to reduce risk of bacteria and with mixing valve to reduce the use of hot water.

To me it seems like a waste of hot water to heat it up and then cool it down and also more standby loss at 140F.

I fail to see any difference between mixing hot and cold at the water heater vs the shower valve.

Galen: There is a difference for some people. Children and those with health problems may get scalded if there’s no mixing valve and water that’s really hot. A person can get burned sometimes because they can’t feel how hot the water is, but it’s still hot enough to scald.

The difference is whether the entire pipe feeding the shower is at legionella growth temperature or legionella death temperature.

For fixtures that are not used a lot that can be a very big difference indeed.

I design commercial hot water heating system systems professionally. Not a bacteriologist, but fairly well informed on the issue.

The risk is not just the presence or even the quantity of the bacteria, it’s the concentration. It needs appropriate temperatures and biofilm to live in. It needs to be in relatively high concentration to cause problematic infections. We fight off low levels all the time.

The only way to intentionally design a plumbing system to defeat this positively without regard to any use factors is high temperature storage with elevated temperature recirculation, like Europe requires, which is essentially a mixing valve at every fixture and circulation of hot water through the pipes. That’s a robust measure. It’s also less energy efficient and and overkill for most situations, and expensive.

The water heater tank is not a likely vector for high concentration bacterial growth. Assuming the home is occupied full time, you are diluting any concentration every time you use hot water, it’s hot enough to inhibit growth, and the volume to surface area ratio is the most favorable for safety anywhere in the hot water system.

Part time residence should either drain water heaters or use on demands or raise the storage temp if not occupied for long periods of time. Normal homes though, it’s really not the water heater to worry about if you are at 120 plus.

That said, infrequently used plumbing lines can be an issue. They have lots of surface area for small water volumes. They aren’t diluted regularly. And while the bacteria wants warm temperatures, given enough time, warm homes in the summer could allow growth, or if plumbing pipes are finding heat from other sources like hot water lines.

Setting your water heater hotter won’t stop that, and if you have a mixing valve, that blends cold water in that bypasses the water heater anyway, so you aren’t even sanitizing on the way through.

Also worth noting, on demands don’t protect against this vector either.

Usually these are sinks with limited aerosolization potential. But if it’s a shower that’s a higher risk.

The ifs ands and buts are why Europe went to high temp recirc. It is literally the only way to be sure. But in my personal opinion, for normal, regular hot water users, your water heater setting at 120 is not the issue to be concerned about.

Thanks for the post Allison

My company has always installed indirect water heaters, boiler fired stainless tanks with stainless coils. A good indirect tank will include heating surface in the bottom of the tank. The boiler will have specific water heating controls and schedules including periodic legionella tank heating schedule. The temperature of the indirect is controlled by the boiler with a 10k sensor so the boiler “knows” the temperature in the tank in a way that an aqua stat or a dumb temperature switch cannot. The boiler controls a small. stainless or bronze recirc pump to deliver hot water to the tap. My customers are used to >120°f at the tap.

I’ve always taken think there are liability issues with legionella serious ; if you are in the business and seed the field with lots of equipment then you play a statistics game that only lawyers win. 🙂

In the radiant heating business, there an extremely bad idea where the incautious and irresponsible promote “open” radiant heating systems which make water heaters double as boilers and directly circulate low temperature fresh, and otherwise “potable” water through their floors. This of course is a remarkably bad idea that can only make unwary eligible for the Darwin awards! 😉

Using a water heater is one effective strategy to help prevent Legionnaires’ disease, which is caused by the Legionella bacteria commonly found in water systems. Legionella thrives in warm water but does not survive at higher temperatures. Here are steps you can take using a water heater:

Set the Correct Temperature: The most effective way to control Legionella growth is by maintaining the water temperature in your heater. Set your water heater to at least 140 degrees Fahrenheit (60 degrees Celsius). This temperature is generally sufficient to kill or inhibit the growth of Legionella bacteria.

Regular Maintenance: Regularly flush out your water heater to remove sediment that can harbor bacteria and reduce heating efficiency. Annual inspections and maintenance by a professional are recommended to ensure optimal operation and safety.

Temperature Balancing: Since water at 140 degrees Fahrenheit can cause scalding, it is essential to install thermostatic mixing valves near the point of use. These valves mix cold water with the hot water from the heater, delivering water at a safe temperature while allowing the heater to maintain a high enough temperature to limit bacterial growth.

Avoid Stagnation: Ensure that all water in the system, including remote taps and rarely used outlets, is regularly turned on and allowed to run to flush the system. Stagnant water is a potential breeding ground for Legionella.

Consider System Design: In larger buildings, consider consulting a water safety specialist to design a system that minimizes dead legs (sections of pipe where water stagnates) and ensures proper circulation and turnover of water.

Implementing these measures as part of a broader water management program can help significantly reduce the risk of Legionella growth and help prevent Legionnaires’ disease.

Are there issues with hard water interfering with mixer valve operation, at the water heater or at the fixtures, as they age?

Yes

Also sediment and calcium in the bottom of tanks promotes legionnaires

Hello and yes. Hardness from the water can build up and freeze what should be moving parts in mixing valves. One approach that can help is to install the valve so it cannot see the heat from the water heater all of the time. Install a heat trap between tank and valve, so the valve is only hot when running water. Also, it’s a good idea to install the valve so there is adequate room for servicing it easily. This may also mean adding isolation valves so it can be played with without a lot of disruption. Lastly, it might be a good idea to keep som spare parts for the valve on hand. That way, you can just swap parts quickly. Then soak the limed up parts in vinegar to get their function back. Save the cleaned parts for the next swap.

Yours, Larry

Thanks Larry. Can you elaborate just a bit on the heat trap. What would it involve? Would there be ongoing added

heat losses?

–John

Hi John, Apologies for this tardy response. There are two basic ways to create a heat trap. The trap is essentially an upside down “U”, and should be a minimum of six inches deep. One approach is to build of of copper pipe and fittings. The other way is to use a long water heater flex connector and bend it into the desired shape. I would insulate the line to keep losses low. Also, there will be some conductive transfer through the copper pipe, but the mixing valve will live at a much lower temperature, and have far less scaling troubles.

Yours, Larry

Legionella is an aerobic bacteria. It needs air (oxygen) to grow. While some air is dissolved in water, it seems unlikely Legionella would grow in water lines or tanks without air bubbles or headspace present.

Fresh water is saturated with oxygen.

Dale,

The amount of oxygen in water is far lower than in air. Bacteria tend to live nearer to the surface of water where oxygen is far more plentiful.

As a winemaker, a main part my job is to limit exposure to oxygen. We regularly top our oak wine barrels to limit oxidation and limit the growth of aerobic contamination bacteria, such as acetobacter.

Legionella is real and definitely grows in fresh water, so apparently there is enough oxygen in the water to grow the organism. There is no question about the potential danger posed by standing luke warm fresh water.

It’s why we never use fresh water in hydronic heating systems. Hydronic heating systems must be closed loop with no fresh water introduction. Introducing much fresh water, (as in auto make up valves) or using piping materials that are not oxygen tight with encourage gas exchange through the material into the heating water causing corrosion issues, especially with iron and steel system components. Typically the PEX tubing we use in floor heating system is coated with Ethyl Vinyl Alcohol, EVOH, to limit oxygen exchange though otherwise permeable polyethylene.

Dale,

My point is that knowing that Legionella is aerobic will help inform you how Legionella will grow at different rates in different locations in a system with varying conditions. Conditions for bacterial growth do vary in a household water system.

My wine example is valid. Growth of aerobic bacteria is inhibited by keeping headspace to a minimum. For example, if your whole house filter housing gets air in it, it will be more likely to get contaminated by aerobic bacteria.

Your example closed system was designed specifically to inhibit aerobic bacteria by limiting the presence of oxygen. The system designer must have thought it was important. But, somehow you know it isn’t an important factor in an open system.

Hello Brad,

Not sure what point your making.

I think the oxygen source to support the bacterial growth we are concerned with is in solution inthe incoming fresh domestic water which is turned over. There is no air space or “head space”.

Dale,

Oxygen is only one factor in the growth of aerobic bacteria. Bacteria do need nutrients. Aerobic bacteria grow better on surfaces rather than suspended in a liquid.

A household water system doesn’t appear to be homogeneous to me. Faucets, shower heads, drains are all part of a household water system and they are a quite different environment from a water line. Bacterial growth is far more likely in a sink drain than in a water line.

A pipe with significant flow is quite a different environment from a pipe with little or no flow. A cold water pipe is quite a different environment than a hot water pipe. Pex is different from copper. Plastic is air permeable. Copper is air-tight and anti-bacterial.

A stagnant pipe could facilitate some biofilm growth because flow will not wash it away before a significant amount forms. A stagnant pipe could effectively become a closed system with very low concentrations of oxygen. No effective source of oxygen flowing into the stagnant pipe. A stagnant pipe could end up with some headspace as gases do not stay 100% in solution. Disinfectant concentration will dissipate in a stagnant pipe. Some of these factors encourage bacterial growth and some do not.

A whole house filter could easily have headspace if not purged when the filter is replaced.

Legionnaires grows in the sediment and calcium at the bottom of the tank

How well?

Humans can survive in the desert, but Death Valley is not the first place I would choose to look for them, especially not if I was looking for a large population.

Can we agree that the higher the temperature, the quicker the kill time for Legionella? Can we agree that metal is a very good conductor of heat? So, when the flame on my gas heater is turned on by the thermostat, doesn’t the bottom of the tank get pretty hot in order to transfer heat to the tank, and heat the water in a reasonable amount of time? Sounds like the bottom of my tank is kinda like Death Valley for Legionella.

Legionella are aerobic. I think it’s an extremely important characteristic that is useful to know, but everyone else is free to think otherwise.

And how often does Legionnaires occur? Goodness!

No idea where my water heater is set, but it is hot enough for me to shower without cold water mixing.

What are the effects of chlorine and water softener salt on bacteria? I don’t inhale my water either. I have no hot tub or steamer.

If this was a thing some institution would create a lobby to mandate through building codes to add some expensive system to mitigate the risk. Like what EPA did to us with radon. Look up how unscientific EPAs determination of what an unsafe radon exposure is in a home. Total BS, the stinky kind of BS.