10 Ways to Reduce Your Indoor Humidity

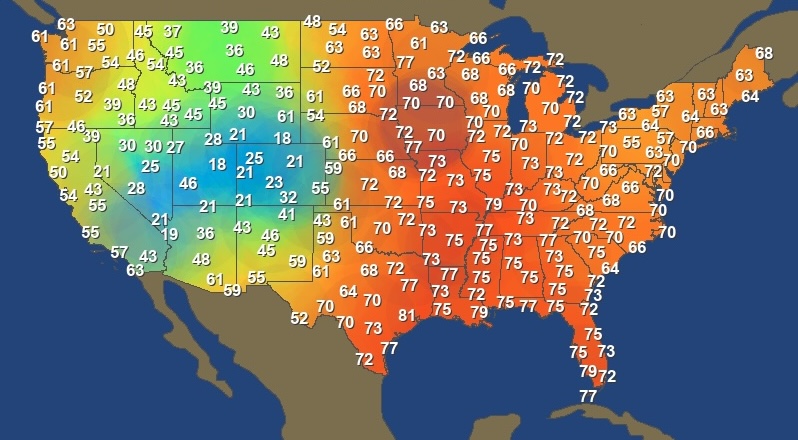

With our changing climate, more people are having to deal with higher humidity for longer periods of time this summer. I’d say this has been probably the worst summer for humidity since I moved to Georgia in the summer of 2000. The map above shows dew point temperatures across the US as I began writing this article on this July afternoon, with some very high numbers on the eastern side of the country.

So, how do you stay comfortable in your home when the outdoor humidity is so high? Let’s take a look at some options…and I’ve got nine things you can do before you crank up that dehumidifier.

1. Keep doors and windows closed.

This one seems like it should be a no-brainer, right? If the outdoor humidity is high, don’t let it get into the house. (If you don’t have air conditioning, that’s a different story.)

When you’re not sure if it’s too humid to open the windows or not, you can follow the guidance I gave in this article. In short, my advice there was to look at the outdoor dew point temperature. If it’s above 60 °F (15 °C), close ’em!

2. Run the bath fans and range hood only enough to do their jobs.

When you’re generating moisture or indoor air pollutants in bathrooms or the kitchen, running those exhaust fans is a good thing. But too much of a good thing can be bad. When exhaust fans keep running, they begin to bring in air that’s more humid than the air they’re exhausting.

To help limit their operation, use a timer on your bath fans or pay attention to when you think it’s OK to turn off the fan. But please do use the range hood when you’re cooking to help your indoor air quality.

3. Keep pots covered when cooking.

Many range hoods have poor capture efficiency. Take a look at your range hood when you’re boiling water with the range hood turned on and see how much of the steam spills out of the hood. It’s not pretty. You can limit the amount of water vapor that gets into your indoor air from cooking by keeping pots and pans covered when suitable.

4. Take shorter showers and baths.

Another source of indoor humidity comes from the bathroom. Every time you shower or bathe, fast-moving water molecules go from the liquid to vapor state.

The longer that hot water comes out of the shower head or sits in the bathtub, the more that conversion happens…and the higher your indoor humidity goes.

5. Seal the big air leaks in your attic and crawl space.

This is like number 1 in this list…except the windows and doors are open 24/7. Find the big holes and seal them. Then go for the medium sized holes and finally the small holes. (Read more about air sealing here.)

If you’re not able to or don’t want to go into the attic or crawl space to do this, hire a company to do it for you. This is some of the lowest hanging fruit to make your house more comfortable, energy efficient, healthy, and durable.

6. Seal the leaks in your duct system.

Duct leakage can add more moisture to your indoor air, too. When the return ducts leak in unconditioned spaces like attics or crawl spaces, they suck in the humid unconditioned air near the leaks. Yes, it passes through the air conditioner, which can remove some of that moisture. But the extra moisture load means the AC might not be able to dehumidify enough.

The other way duct leakage can make your house more humid is if the leakage outside the conditioned space is unbalanced. By that I mean that the ducts leak either more on the supply side or more on the return side. If the supply ducts leak more than the return ducts, the pressure inside your house becomes negative relative to outdoors. That causes outdoor air to infiltrate, bringing all its humidity with it. For a more complete explanation of this phenomenon, see my article explaining duct leakage.

7. Experiment with the thermostat setpoint to find your comfort sweet spot.

One way to dehumidify more is to lower the setpoint on the thermostat. But if you lower it too much, you end up with a house that’s cold and clammy. That’s not comfortable.

So get yourself a digital thermo-hygrometer*—with remote sensors if you want to measure the temperature and relative humidity in multiple places. Try different settings on the thermostat and watch what happens to the temperature and relative humidity. To get a better handle on what’s happening with the humidity, get an app that can convert those numbers to the dew point temperature.

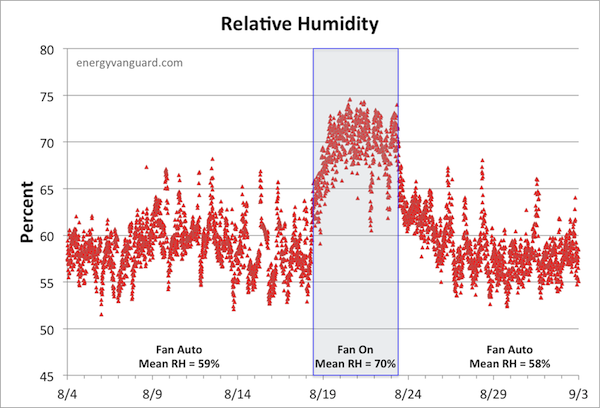

8. Make sure the fan on your air conditioner is set to “auto.”

There are two good reasons you don’t want the fan on your central air conditioner to run continuously in a humid climate. First, the air conditioner gets cold and condenses water from the air passing over the coil. When that water drips down and drains away, the AC has helped dehumidify your indoor air.

But when the compressor goes off, the coil warms up. If the fan keeps running then, the coil isn’t cold enough to condense water from the air. Worse, the air blowing over the coil causes the water that’s still sitting there to evaporate back into the air, raising the relative humidity in your home. I know because I saw this in my own house (graph below, details here).

Second, leaky ducts can create more infiltration. With the fan running continuously, the ducts leak continuously. See number 6 above for why that can make your home more humid.

9. Get an HVAC professional to check your air conditioner’s air flow.

How well an air conditioner dehumidifies depends on a number of factors. An important one is how fast the air moves across the coil, called the air flow rate. In humid climates where dehumidification is important, you want that air flow rate to be about 350 cubic feet per minute (cfm) or less. (Full explanation here.)

Measuring the air flow rate takes equipment and skills that most homeowners don’t have, so you’ll probably have to call an HVAC pro to do that measurement for you.

10. Use a dehumidifier.

Finally, if you’ve done all you can or are willing to do, it’s time to use a dehumidifier. The one below is a whole-house dehumidifier that can pull the air from one place and send the dehumidified air somewhere else. You also could use a regular room dehumidifier.

And there you have it. In summary, first you reduce the amount of moisture you’re adding to your indoor air (items 1 through 6). Then you optimize the mechanical systems to get the humidity where you want it.

How’s your house doing this year? Mine is worse than usual for two reasons: There’s more outdoor humidity, and we’re bringing more of it indoors because of our ongoing basement renovation. I’ve done as much of the stuff above as I can do, and I’ve got a dehumidifier running right now, too.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can follow Allison on LinkedIn and subscribe to Energy Vanguard’s weekly newsletter and YouTube channel.

* This is an Amazon Associate link. You pay the same price you would pay normally, but Energy Vanguard may make a small commission if you buy after using the link.

Related Articles

Five Fun Facts About Dew Point Temperature

Comments are welcome and moderated. Your comment will appear below after approval.

I don’t usually run my bathroom exhaust fan during a shower when it is hot and humid out. When I get done mowing the lawn on a day where it is 95 F DB and 75 F DP outside and take a shower, my bath fan would be exhausting 75 F saturated air (DB and DP) at best while causing additional air to be sucked into the house somewhere else at 95 F DB and 75 F DP. Thus, I haven’t reduced my latent load, but I have increased my sensible load. The AC is likely to be running quite a bit under those conditions, so it will remove the additional moisture. If the bathroom is fogged up, just open the door afterwards and let it circulate with the rest of the house.

Roy: Thanks for bringing in a more nuanced approach to running the bath fan during or after a shower. As with opening the windows, your suggestion to do a dew point comparison is a good approach. Now, you say the air in your bathroom is 75 °F and 100 % relative humidity. Have you measured that? My bathroom gets a bit warmer when I shower, which would raise the dew point, too.

For others reading this, a good approach here would be to look at your bathroom air temperature and the outdoor dew point. The dew point in your bathroom during a shower is probably the same as the air temperature. If that number is higher than the outdoor dew point, run the bath fan. If it’s lower, leave it off because you’d just be bringing air with more humidity into the house.

If you install the exhaust fan directly over the shower stall and the shower stall is well enclosed, than you might be exhausting higher temperature saturated air that is higher dewpoint than outdoors. Most bath exhaust fans that I have seen are installed in the middle of the bathroom, not over the shower, thus the shower air is diluted by the air in the rest of the bathroom before it gets to the exhaust fan. It would be good to do some measurements to see if this is true.

Hmm. If you run your exhaust-only bath fan even when the outdoor dewpoint is high, would it be a huge problem? The infiltration caused by depressurization would most likely occur in many locations in the envelope and there would be mixing throughout a presumably larger volume. If the bath fan is on a timer and doesn’t run all day, is the mixing of infiltrated humidity with cooler, drier air a big problem?

On the other hand, even if the outdoor dewpoint is lower than the bath dewpoint, infiltration of humid air can still be condensation/mold risk in a dark, wood frame stud cavity.

It points to the benefit of balanced ventilation with humidity recovery.

Does item 8, the advice to make sure the air conditioner fan is set to Auto, rather than to ON, apply to ducted mini-splits (specifically Mitsu ducted mini)? I was told to keep the fan in the system on 24/7/365, so my t-stats are set to that…

cal: Yes, it does apply to ducted mini-splits, too. My Mitsubishi thermostats (MHK2) have four modes for the fan: Auto, I, II, and III. (I, II, and III are low, medium, & high.) I keep them in Auto mode unless I’m measuring the pressure drop across the filters or something where I need a different fan speed. But Auto on these systems keeps the fan running continuously. Since it’s a variable speed system, the Auto mode ramps the fan speed up and down as necessary when the compressor ramps up or down.

There is a way to set it to make the fan go off when the compressor goes off. You can’t do it from the main screen, though. You have to go into the installer settings. We just had to deal with that for a client yesterday because he keeps the thermostat at 78 °F and has two indoor units on one outdoor unit. That resulted in a problem where the system “overcooled” the house. Changing that setting should solve the problem for him.

Thank you. Appreciate the response.

I now remember rooting around in the installer setup menu a few years ago to make the fan run all the time in auto, because I read that either here or at GBA, so that is why and how mine are always on. I’m not the client you worked for yesterday, but have a similar setup and also keep my t-stats at 78.

Hopefully you will do a future article on how your client’s situation resulted in overcooling! Very curious.

To add to the airflow over the coil issue. This is a bigger issue as the efficiency of the AC unit goes up and also an issue with the common practice of upping efficiency by using a larger coil. IE a 4 ton coil with a 3.5 ton condenser is typically done to increase the seer of a system but it increases indoor humidity.

Energy efficiency is a great thing but it’s often at odds with comfort and what you are trying to accomplish and creates new problems to solve that cost $ in equipment and then the accompanying energy use to run it. So make sure to look at the big picture as you might not always want a super efficient unit if it requires more ancillary equipment and energy to run it not to mention that the higher efficiency systems also cost more and are more failure prone.

Now that AC temp sweetspot… Has allot to do with the issues I stated above and if you are running high seer equipment it’s more of an issue. And same with units that have very high airflow for other reasons. Hotels have this problem as they move way too much air over the coils and they will get a room cold but never get enough moisture out. Common believed cause for that is that the unit is oversized which is incorrect. The unit will run non stop for hours on end and never pull much moisture out. The better half spends about half the year in hotels and I do as well and are well aware of what is wrong with their setups.

Getting that sweetspot on those systems isn’t possible however if it’s a system where you can block some of the air flow to it you can force it to pull moisture out then unblock it to let it cool.

As for our house we are NW of FTW and it’s not a dry climate like many tend to think. It’s been closer to a normal summer this year which is very nice and moisture wise inside no issues as it hovers around 50%. Which that said I personally prefer and am much more comfortable with 25%-35% or even lower outdoors.

I did add a pallet of blow in insulation last fall which made a difference over the winter and we used about 300KWH less in June vs the previous year. I also changed out to a GE thermostat as I wanted remote control without all the annoyances of the nest style t stats. It handles run time differently than the old one.

And as for the cooking part. Here in TX summer is the not cooking inside season. Cooking releases so much heat and humidity into the house and the AC is already running non stop in most houses so you do very little of it outside of the microwave and other low heat impact cooking items. And many people eat out more in the summer because of it. I cook allot on the grill and stuff like smoking a brisket we have many meals that we can thaw out and warm up in the microwave.

What I would like to do this winter is replace our condenser with a heatpump condenser. (coil is a heatpump version) Since we use basically no nat gas for most months of the year and are paying $25 a month for the availability of it… I’m all for getting rid of that fee and going with a heat pump. Our oven is the only other gas appliance however if we didn’t have it we wouldn’t notice since it’s just the two of us and we use an induction burner and a small convection (air fryer)oven.

I would convert the furnace to propane and then have that as an emergency backup.

Robert: Thanks for all the good points in your comment. Another issue is that with variable capacity systems, the compressor and blower aren’t always synchronized to ramp up and down by the same amount. You may be at 350 cfm/ton at high speed, but then it might go up to 400 or higher at low speed. It depends on the system and the controls.

Running my loft mini-split in “drying” mode seems to do the trick and is a lot less expensive than adding a whole house dehumidifier. The only drawback is this mode has no temperature shut-off. Bummer.

Norman: Yeah, dry mode will do more dehumidification, but you lose control of the temperature as it just keeps cooling.

We have had a chronic humidity problem in our 1980’s home in Katy Tx. We had a whole home dehumidifier installed but it really didn’t help the issue we couldn’t get the humidity below 60% with the A/C and dehumidifier running.

We then completely replaced the A/C system. We had hired a home energy auditor and had the house and ducts tested Ann’s the contract we wrote up required the new system to pass the tests.

We ended up with a variable speed Lennox heat pump. For the first time in 30 years we could get it down to 55%. But it should be lower. We finally replaced the sliding glass door with a built in dog door. That was what the house needed. We no longer need the dehumidifier at all the heat pump does a great job of controlling the humidity at 50% we could even go lower if we wanted.

I would not have gone to that trouble and expense if not for what I’ve learned from you here. We even gave copies of your book to the owner of the company and the installation crew.

Now we just have to worry about co2 build up. With 3 adults and a couple of dogs without the fresh air on the co2 levels climb above 800.

🤷🏼♂️

The trend here in Michigan seems to be higher dew points as well. Glancing at Weather Underground we’ve had 26/30 days in July above a 60F dew point and 8/30 above 70F. High daily average 73F. The rest of this week is suppose to hover around 70F. This just doesn’t seem like the old days, when I remember the odd couple days of truly steamy weather in the summer.

I’d like to see some real historical data though. What’s your favorite source for dew point data over the years??

I’ve got one more question to throw out…

If you had to choose between having a dehumidifier or an air conditioner in your home, you can only have one or the other, which would you choose and Why?

A very good list. Would you add the costlier inverter variable compressor systems where some brands make big claims of humidity removal? And some heat pump systems can be configured to use A/C and strip heat simultaneously to achieve “re-heat” dehumidification and avoid the ERV’s and separate dehu’s?

Yes to Inverter systems and from experience it’s not just a claim. That said, there’s “combo” designs integrating ductless into ducted designs. These will remove humidity better than traditional ductless but not as good as inverter technology I am referencing (Ex. Carrier Infinity 24VNA9/6 or 25VNA8/4). With proper installation and duct design, these will remove a great deal of moisture therefore I am fan of spending money the HVAC system that will suit both needs. 24VNA936/58CVA070 and 24VNA924/59TN6B060 in Atlanta for reference I stay steady 71 and 55RH.

Re-heat is unbelievable expensive for dehum. For the cost, I’d put money into the inverter. ERVs are all too often turned off at some point, particularly in high humidity areas and I am not a huge fan personally, although they have their places. While house dehums are cheaper options (albeit not cheap) and with proper design can work extremely well.

We just built a new home. It’s fairly tight at ACH50 =1.7 and insulated. We are in central VA where humidity is routinely high. We have a variable capacity HP (Carrier Infinity/ Greenspeed) that periodically runs in a “dehumidifier “ mode that is low-level fan + an older 70-pint/ day stand alone dehumidifier from the old house. Result: 40-43 percent humidity even in the worst summer days. And, my AC only drops the temp about 1/2 degree F to supplement on those really humid days…so no overly-cold rooms. So, variable speed AC and a small dehumidifier (and tight house) really works well. As far as the CO2 levels…we are struggling to manage them without near 100% running of our ERV. Hmm 🤔

One thing that sometimes gets overlooked is the proper refrigerant charge in the A/C unit. The evaporator coil needs to be around 45° or below to dehumidify properly. If the system has too little or has too much refrigerant it will still cool the space but it won’t drain enough moisture from the air. My brother and I both are HVAC techs- he mentioned an apt. he worked on a couple weeks ago where the RH% was the resident complaint even though the room temp was ok. Turned out that the maintenance man had added way TOO much refrigerant in the unit. Once he recovered 3 pounds of R410A from the system he said the coil was draining water like a water faucet.

I have a whole house dehumidifier. The AC turns off at 72-73 and the temp is comfortable. However the humidity is like 65-70 even with the whole house running. Is that maybe my fireplace is drafting warm outside humid air?

Some arguments gains your point 8 is that continuous fan operation filter the air more and is crucial if you have allergies. Also, there is some value comfort wise in having continuous air circulation.

Still you make good point for having the fan in auto. I would especially say to be in auto if you have humidity issues.

Hi Allison! Items 1 and 2 in your list are both addressing the need for ventilation. Another way to combat humidity is to use an ERV to achieve ventilation. If the interior climate is being controlled thermally with recirculating AC, a good ERV will improve indoor air quality while rejecting as much as 2/3 of the outdoor humidity.

Does your dehumidifier have a fresh-air intake? Mine does, and I love it, but I had to really choke down the fresh air, because it was injecting so much humid air that my dehumidifier was losing the battle.

I “closed” the fresh air damper, and removed the filter for the return air from the house at the vent (the air still passes through a filter on the dehumidifier) so most of the air was coming from the house rather than the outside. It can now properly dehumidify the house, and if I want to introduce more fresh air, I can simply either lower the humidity setting, or to save some money, turn my HVAC fan to CIRC so it will push some of the air from one vacant area of the house to the occupied area (from the bedrooms to the den, and vice-versa at night).

My dehumidifier uses my HVAC fan to push the air through my house (I know that might be controversial, but that’s how the contractor installed it, and it works), so using CIRC to circulate air isn’t doing anything worse (meaning running air through the unconditioned attic) than what the dehumidifier does, and with CIRC, at least my dehumidifier isn’t running as much.