7 Steps to Good Indoor Air Quality

Breathing clean, healthy air at home doesn’t happen by accident. And it’s not something you can buy a magic product to do for you. No, it’s the result of understanding the basic measures that work to keep your air clean. Here I’ve distilled it down to 7 steps to good indoor air quality.

1. Source control

The first step is to pay attention. Buying furniture or carpet? Look for products that won’t offgas a lot of volatile organic compounds (VOC) like formaldehyde or benzene. A lot of building products offgas VOCs, too. As do cleaning products, air fresheners, and pretty much anything that’s scented. Take a look at your AC filter after burning scented candles for a while and see some of the stuff you’ve been breathing.

![Scented candles are bad for indoor air quality. [Photo by slgckgc from flickr.com, CC BY 2.0]](https://www.energyvanguard.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/scented-candle-indoor-air-quality-720.jpg)

- VOC barriers – Drywall over spray foam is an example.

- Material conditioning – Leave it in a well-ventilated space for a while before bringing it indoors.

- Staged entry of materials – Leave materials in a well-ventilated space and bring them in as needed rather than all at once.

- Building flush-out – Use a high ventilation rate, run the air handlers, and open windows for a while.

- Delayed occupancy – Let the offgassing do its thing and start diminishing before bringing the people in.

- Higher ventilation rates early on – Run the ventilation more when the construction or remodeling is first done and ramp down later.

We’ve known the importance of source control for a long time. In 1858, a fellow named Max von Pettenkofer said, “If there is a pile of manure in a space, do not try to remove the odor by ventilation. Remove the pile of manure.”

2. Airtightness

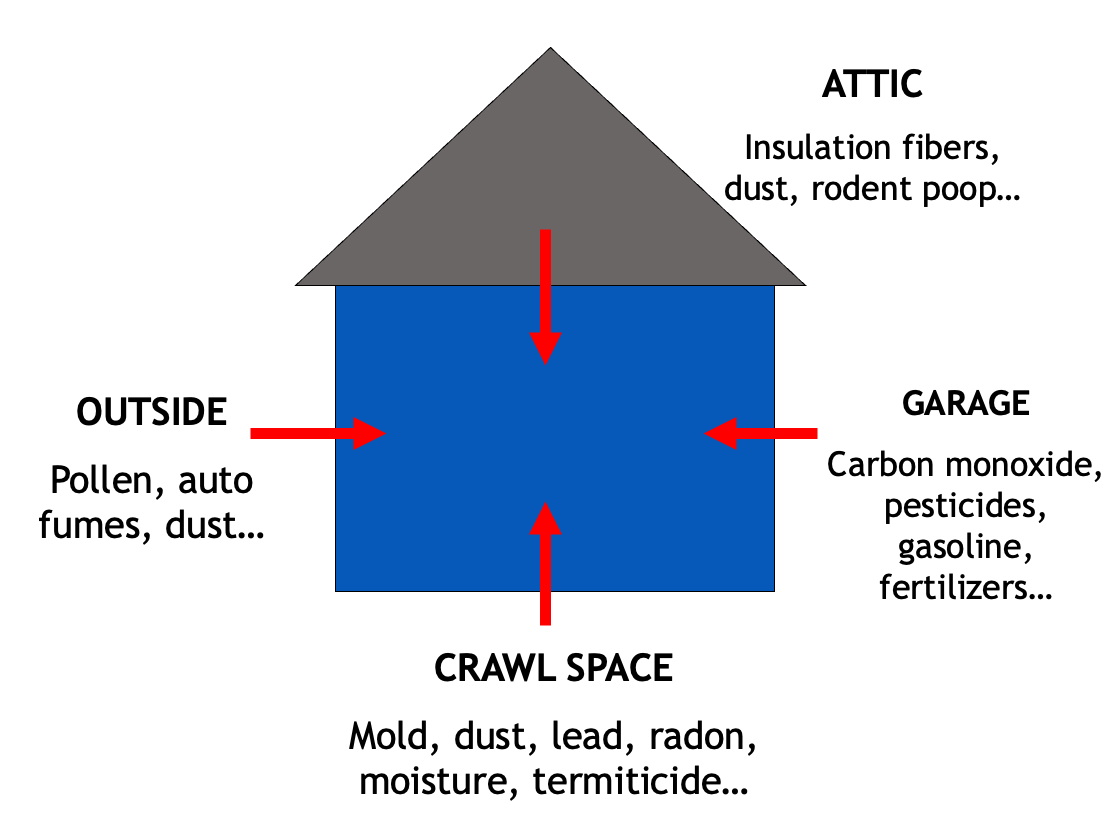

One of the questions you need to ask when investigating indoor air quality is, “Where are the pollutants coming from?” And one of the answers is that they’re coming from outside the conditioned space. That doesn’t just mean the outdoors, though. Bad stuff comes from an attached garage, a moldy crawl space or basement, and a dirty attic. Even air from the outdoors isn’t always cleaner than indoor air.

Despite the myth that a house needs to breathe, airtightness is one of the essential steps for good indoor air quality. Airtightness is good for more than just IAQ, too. It improves comfort by reducing drafts and heat transfer. It’s good for durability because a lot of water vapor moves with air, too. And when water vapor gets into the wrong places, it can become an IAQ problem as well. (See number 5 below.) And of course it’s good for reducing energy waste.

(Busting this myth about houses needing to breathe is such a big deal that I even used it as the title of my book: A House Needs to Breathe…Or Does It? The answer is no and given on page 23.)

3. Filtration

Another question to ask about indoor air pollutants is, “Is it a particle or a gas?” If it’s a particle, we can remove it with media filters. But for good IAQ, we have to up our filtration game. The standard 1 inch deep fiberglass filter can remove the big particles, but it’s the tiny particles that matter most for health. That’s because they can penetrate deep into the lungs. From there, they get into the bloodstream, which takes them to the heart and brain. And that can increase your risk for heart attack, stroke, asthma, COPD, and more.

No, the 1 inch fiberglass filter just won’t do. The good news is that you can use a media filter with a much higher efficiency in your HVAC system if it’s sized properly. Filter efficiency is best measured with something called Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value, or MERV. The ratings go from 1 to 16, and you want to go with MERV 13. That gives you the best balance between filtration efficiency and resistance to air flow.

In addition to improving the filtration in your heating and cooling system, you can add standalone filtration. Portable HEPA filters work well. Another option is the do-it-yourself Corsi-Rosenthal box fan air cleaner made with 4 MERV 13 filters and a box fan.

4. Ventilation

Now let’s talk about the other answer to that question from the filtration step above. If the pollutant is a gas and source control hasn’t kept it out, whole-house mechanical ventilation is generally our next best option. We dilute the pollutants in the indoor air by bringing in more outdoor air.

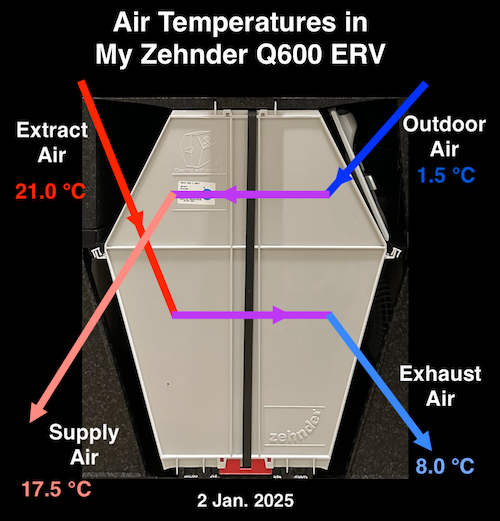

We can ventilate a home in many ways. They’re not all equivalent. A balanced ventilation system would both exhaust air from the house and introduce outdoor air into the house. A balanced system with heat recovery would send the two air streams through a heat exchanger so you’re not losing all that heating or cooling you paid to put into your indoor air. That type of system is called a heat recovery ventilator (HRV).

For most homes, a balanced system with heat and moisture recovery would be best. In addition to recovering heat, it also recovers moisture. That keeps your indoor air from getting too dry in winter. It also keeps excess humidity out of your home in summer if you live in a humid climate. This type of system is called a energy recovery ventilator (ERV).

However you do it, though, make sure you understand the pros and cons of the system you choose. Then get the ventilation rate right, distribute the air appropriately, and get it commissioned for proper operation. Oh, and then make sure to maintain it. Intake grilles and filters clog easily.

5. Moisture control

When I discuss the building enclosure and control layers, I always put moisture control at the top of the list. That’s because water, especially in its liquid form, causes more damage to homes than any other problem.

It’s also really important for indoor air quality, too. Whether it begins as a liquid or vapor, water that accumulates in the porous materials of a home can hurt indoor air quality. Water is the main lever we have to control microbial growth. Keep things dry, and the microbes aren’t likely to proliferate. Let them get wet and stay wet, and your home becomes a biology experiment.

The solution is controlling water in every way you can. That means good water management at the roof, walls, and foundation. It means insulating cold things like ductwork in an air conditioned home in a humid climate. It may require a dehumidifier.

6. Pressure balancing

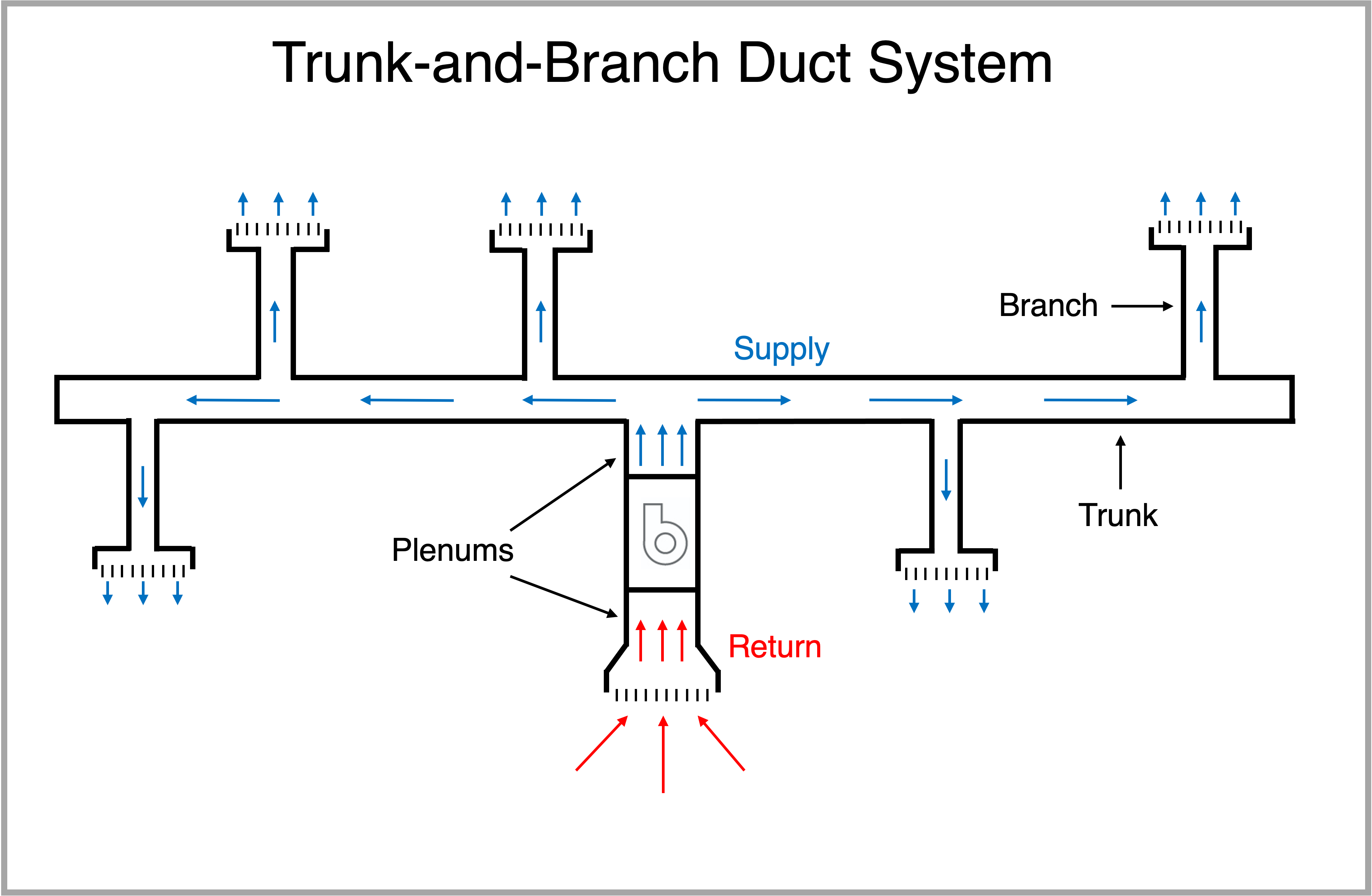

This one may not be so obvious to you. Think of what your ducted heating and cooling system does. The diagram below shows air being blown out of supply vents and pulled into a single return vent. You may never thought of it this way, but even though you can’t see it, there’s a duct connecting the supply vents to the return vents. It’s called your house.

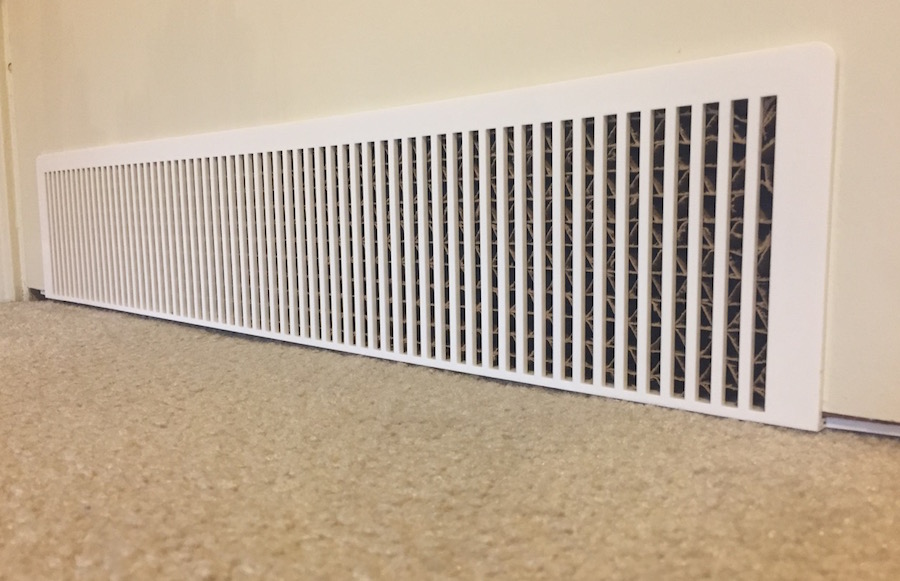

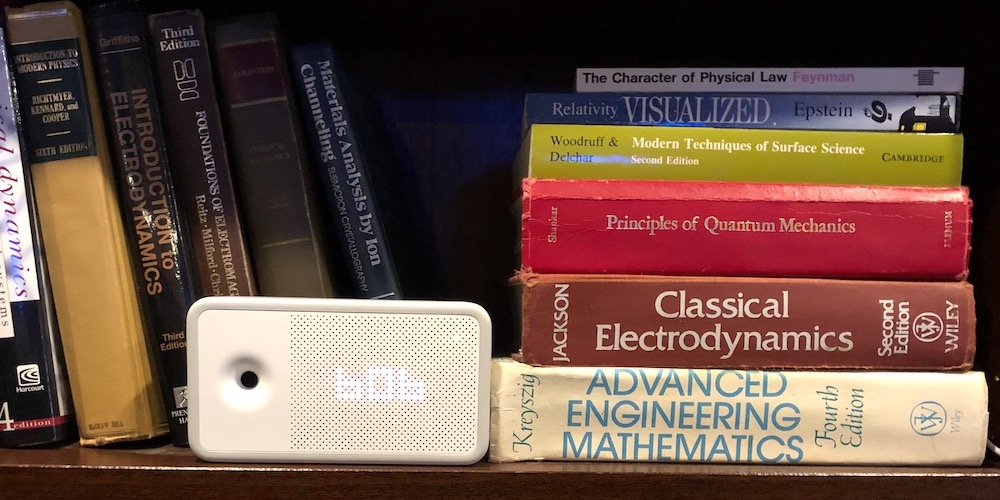

The only problem with that duct called your house is that sometimes it gets blocked. If one of those supply vents is in a bedroom with a closed door, what happens to the air being pumped into the bedroom? For the system to work properly, that air needs to make its way back to the return vent. So it needs a return air pathway. The lead photo at the top shows one called the Perfect Balance by Tamarack.

When a duct system doesn’t have a return air pathway, the bedrooms build up positive pressure when the doors are closed. The area where the central return is develops a negative pressure. And negative pressures suck, literally. They can pull in outdoor air. They can pull in bad air from the garage, crawl space, or attic. They also can pull in humid outdoor air, exacerbating any moisture control problems already in the home.

Worse, negative pressure inside the home can backdraft an open fireplace or natural draft water heater. Pulling in exhaust gases from a wood-burning fireplace can put soot and other combustion products in your home. Pulling exhaust gases from a gas water heater into your home can have you breathing carbon monoxide.

Unbalanced pressures inside the home can have a huge negative impact on your indoor air quality. Make sure you have return air pathways for ducted heating and cooling systems. And be careful with a range hood that exhausts a lot of air. You may need a makeup air system for it if you’re not willing to give it up.

7. IAQ Monitoring

The above six items are important measures you can take to improve your indoor air quality. But how do you know if they’re really helping? Fortunately, we live in an age with a growing number of affordable IAQ monitors.

In my home, I have thermo-hygrometers to keep an eye on temperature and relative humidity. I have two Awair Element monitors and two different Airthings monitors. Those devices allow me to keep an eye on temperature, relative humidity, carbon dioxide, particulates (PM2.5 and PM10), volatile organic compounds, radon, and more. And I have a Defender low-level carbon monoxide monitor.

You don’t have to go crazy with monitoring, which some people might think I’ve done. But monitoring carbon dioxide will tell you how much dilution you’re getting from your ventilation system. Monitoring particulate matter will tell you how good a job you’re doing with filtration. Checking your relative humidity can let you know if you’re cooking too much pasta…or need a better way of dealing will all the moisture you’re adding when you do.

And of course, measuring carbon monoxide and radon can tell if you need to take action to solve those problems.

Closing

Back in 2022 I published an article on a layered approach to indoor air quality (IAQ). We were just coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time, so I focused on control of infectious diseases in that piece. Now you’ve got my more general update for achieving good indoor air quality in homes.

Some things, though, haven’t changed. I still don’t recommend most electronic air cleaners. I know that ultraviolet lamps work, but they’re probably overkill for most residential applications. They’re usually not engineered to zap the viruses and bacteria in the air stream. Yes, they can help keep the coil and drain pan clean, but good filtration with no bypass is a better way to do that.

There’s an old saying that, I believe, goes back to the 1980s: Build tight; ventilate right. It makes an important point. Both airtightness and ventilation are good. And when we make homes more airtight, we also need to consider other measures to ensure good indoor air quality. The only problem with “Build tight; ventilate right” is that it leaves out the other essential factors that contribute to good IAQ. By following the more complete list above, you can improve your indoor air quality and help keep your family safe and healthy.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can follow Allison on LinkedIn and subscribe to Energy Vanguard’s weekly newsletter and YouTube channel.

Related Articles

A Layered Approach to Indoor Air Quality

A Burnt Grilled Cheese and the Collapse of Indoor Air Quality

2 Reasons to Avoid Most Electronic Air Cleaners

Comments are welcome and moderated. Your comment will appear below after approval. To control spam, we close comments after one year.

One of my favorite topics. It’s really important to understand offgasing which for most materials has a half life. Knowing what that half life is for various materials is very difficult. Stacks of brand new books straight from the printing press offgas heavily, for example, and the best strategy with that is to sell more books quickly. OK, I just could not resist…

We have built in offgasing into our daily lives at every step of constructing a home. To begin with, wood framing is offgasing. OSB type boards like wall sheathing and subflooring, plywood, engineered beams, sheetrock, joint compound (various types), insulation of all types, cement-based materials such as concrete, mortar, tile grout and thinset, all paints, stains, and clear coats, caulking and sealants, flooring adhesives, carpets, carpet pads, plastics, wall paper, roof shingles and underlayments, window bug screens, even ceramic or porcelain tile: all offgas VOCs. Flexible duct lining, and duct board in your HVAC system, even your air filter, too.

Your running tap water is offgasing VOCs, especially city water. Your gas stove and cooktop is leaking gas when it’s not in use, and is contributing a “colorful” group of pollutants when you do cook/bake, because it’s gas combustion without any controls whatsoever, such as catalytic filters.

All the fabrics and cloths in your closet, boxes and packaging in your pantry, shoes in your foyer, and that stinky shower curtain that smells like it just left the vinyl factory. Rugs, tapestry, and paintings, photos, reprints, and various art pieces in your house.

With all that, constant, or at least daily ventilation cannot be underestimated. Our human interface to all the offgasing is about the size of a tennis court, i.e. that is the total surface of our lung lining: the alveoli. That’s where efficient gas exchange takes place, but also efficient VOC exchange. If you want to deliver something quickly into our blood stream, use the lungs!

To clarify, I galloped a bit too fast with the tap water on the list. There is still offgasing, but most likely not VOCs (hopefully not). It’s dissolved gases in municipal water like chlorine or chloramine, which are inorganic. A whole house carbon filter usually takes care of that.

Paul: You forgot to mention that we humans are also offgassing. The fancy word for the products of that offgassing is bioeffluents.

Until a couple of months ago, I had forgotten all about that new book smell that we treated you to when you came to pick up your book at our office in 2022. Then our new shipment got delivered, and we got it again. Fortunately, it was a smaller shipment, and the smell dissipated more quickly this time.

Another often overlooked possible pollutant source, from my observations, is carpeting. I am talking about the permanently installed wall-to-wall type. It probably outgasses, at least when new. It sure collects dirt which I don’t think can be completely removed by vacuuming. The padding slowly decomposes (composts?) over time. When you tear out old carpeting, you can find a lot of nasty stuff. I am OK with floor rugs, because you can see what is under them.

Roy: I agree. I was around some new carpet recently, and it smelled nasty. And when we bought out house in 2019, one of the first things I did was rip out the old carpet. It was beyond nasty.

How bad are scented candles for IAQ, really? I’ve read several times that they are bad, and they are at the top of this list. But in the context of all pollutants, where do scented candles rank?

My better half is quite accommodating to my various home improvements designed to improve efficiency and health even though she doesn’t understand why they are important (and even though she doesn’t know anyone else that does these things to their home). But telling her we have to ditch scented candles may be a bridge too far! She loves those things and looks forward to new seasonal scents every few months.

Why take a chance on putting anything in the air that is not necessary? Manufacturers of things that smell good claim that they are safe, but I guess I just don’t trust them. Why take a chance?

Marital bliss? 😀

I guess I look at it the same way as eating a double cheeseburger with fries, onion rings, and frozen custard for desert. I know it is not good for me and might take some measurable amount of time off my life. But I also only eat that way occasionally and am not expecting to drop dead in my 60s because of it. Why live a life with no joy?

As for indoor air pollutants: I understand being mindful of products that emit VOCs incidentally to their main purpose (e.g., building materials). Why expose yourself to stinky offgasses for no good reason?

But let’s keep it in context. The explicit purpose of scented candles is to emit a smell – one that is pleasurable, not noxious. And exposure for most people would be measurable in single or low double-digit hours per week, not continuous. I’m not an expert on the topic, but a quick search of the research literature suggests that although scented candles do emit VOCs, they are not considered dangerous under normal conditions.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.02.010

“On the basis of this investigation it was concluded that under normal conditions of use scented candles do not pose known health risks to the consumer.”

At the end of the paper referenced above, it says:

Conflict of Interest

Financial support for this work has been provided by a consortium of companies organized by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials Inc. (RIFM).

Obviously these are the companies that make the candles.

I look at everything in terms of risk/reward tradeoffs. I don’t care how low the risk might be in this case, the reward just isn’t worth it.

I certainly won’t fault anyone using your logic. I typically use the same logic myself.

But in this case, the known risk of an annoyed spouse outweighs the unknown risk of health outcomes attributed to burning candles 🙂 I initially thought I’d find obvious empirical support to back up my default position of not purposely introducing VOCs via scented candles, but in the absence of that evidence, I decided to not bring it up for now.

Well, candles may be a touchy subject. Tradition, customs, etc…

We’re having a conversation about breathing air. Just air. Why add to it? I mean to the air.

Have you ever been on a quiet mountain road? I remember driving on the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina on a crisp spring day, no car in sight. Fresh air, blue sky, life is good. And suddenly, a car shows up coming from the opposite direction. How dare they! But the thing that we noticed the most was the “scent” of the engine exhaust fumes as the car drove by. It was so crisp, identifiable, almost satisfying as if I were a human spectrometer getting a breakdown of elements in those fumes. Well, the latter is a joke. It wasn’t satisfying, but it was eye-opening. When you drive around a city in traffic you don’t smell anything after a while. You adapt, well, your nose/brain adapt. Same thing happens in our homes.

Did you know the blue hue from the Blue Ridge mountains is caused by VOCs emitted by the forest (Primarily terpenes via conifers)?

JC, a very interesting paper: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2701830/

I am guessing I was safe from excessive isoprene inhalation on a crisp spring day on the Blue Ridge Parkway (not too much heat stress for the oaks and poplars at the time).

Yep. It’s in part why back in the early 2000’s Metro-Atlanta was having such a hard time meeting its AQ mandates.

I guess I am lucky that my wife has never felt a need to burn candles or use any type of air “fresheners”. Maybe that is why we have been married 40 years.

I am surprised that the topic of pets as a contaminant source has not appeared on this blog. I put up with people and their off gassing in my house, but I would never have a pet indoors. I am guessing that most of the people on this thread are pet owners.