Are You Making These Mistakes With Your Thermostat

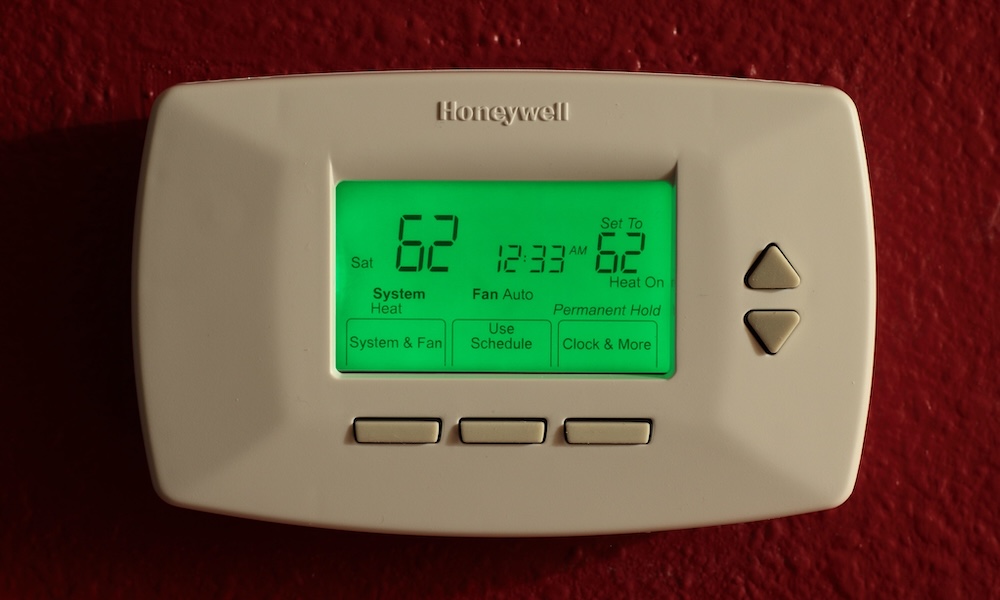

Let’s talk thermostats today. This ubiquitous device in homes is the user interface that allows people to control their heating and cooling systems. It might seem simple. Turn it up when you need more heating or cooling and down when you want less. But there’s a lot more to it than that. Should you do setbacks to save energy? Should you put the fan in the “On” position or leave it in “Auto”? Should you use the “Emergency Heat” setting? Let’s try to sort all this out now.

Deep setbacks with right-sized equipment

Many homes have a heating and cooling system that has two or three times the capacity it needs. You can tell if that’s the case by monitoring how long it runs on a hot afternoon or a cold night. If it runs only 30 minutes an hour when it’s hot or cold, your system is about twice as big as it needs to be. (See my article on design temperatures for the definition of hot and cold for HVAC design purposes.)

This is the main thing you need to know if you’re thinking about using setbacks to save energy. Yes, setbacks do save energy, but that’s mostly true only in leaky, under-insulated houses with oversized heating and cooling systems. If you have a good building enclosure and right-sized (or in my case, undersized) systems, you need to be very conservative with setbacks.

The reason for that is that a right-sized system doesn’t have the capacity to recover quickly. If it’s a design day, setting your thermostat back may make it difficult to get the house back to the temperature you want.

Or maybe you have a heat pump that has auxiliary heat. That just exchanges one problem for another.

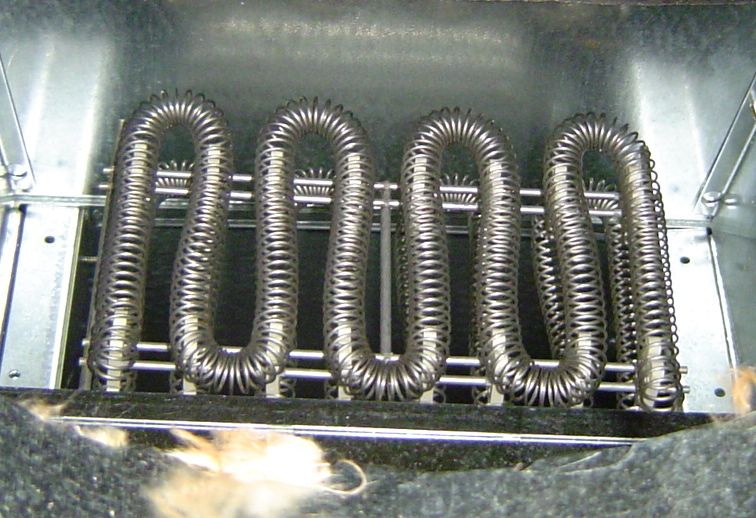

Deep setbacks with electric resistance auxiliary heat

A different problem with setbacks occurs if you have a heat pump with electric resistance auxiliary heat. Say you do a deep setback at night and then turn the thermostat up several degrees in the morning. What happens is that the heat pump will turn on the resistance heat to catch up more quickly. And that can jack up your heating bill significantly.

The heat you get from the heat pump itself is about three times more efficient than the electric resistance heat. So you want the heat pump to provide most or all of your heat. The majority of the hours you heat your home in winter—at least in the places where most people live—are prime heat pump conditions. It’s not too cold for your heat pump to work at high efficiency, so you should be letting your heat pump do most of the work then.

Setting it to “Emergency Heat” because it’s “too cold”

This mistake is way too common for homes with heat pumps. Worse, it’s promoted by some in the HVAC industry who should know better. Installers and technicians sometimes tell homeowners that heat pumps “don’t work” when it’s too cold outside. And their definition of “too cold” varies. Occasionally it’s as high as 45 °F.

And that’s wrong, wrong, wrong! Even heat pumps made for milder climates keep pumping heat as the temperature drops into the teens and single digits or below zero. They just pump less and less as it gets colder. (See my article on the balance point temperature.)

So keep the thermostat set to “Heat.” When the heat pump can’t provide enough heat for the house it will kick on the auxiliary heat to supplement the heat pump. Or if it’s a dual fuel setup, it’ll switch over to the furnace.

Also see the article I wrote about the Emergency Heat setting a while back.

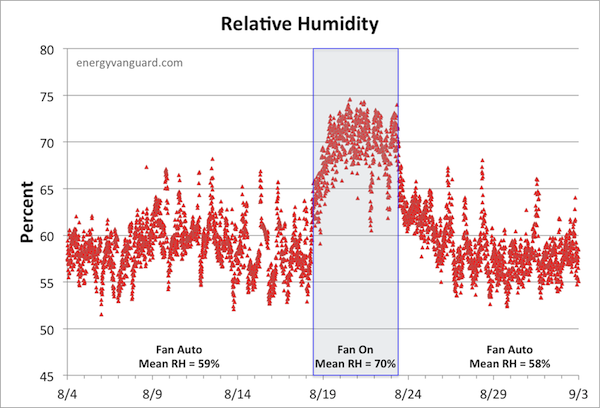

Setting fan to “On” for cooling in a humid climate

In a mixed-humid or hot-humid climate, you need to be really careful with the fan setting. When you’re cooling the house, there’s a dangerous setting that can make your house both less comfortable and less healthy.

In short, the problem is that that setting keeps the fan blowing air over the coil whether the AC is cooling or not. In a humid climate, the coil gets cold and does two jobs: cools the air passing over it and removes humidity from the air passing over it. That second part happens by water vapor condensing on the coil.

By keeping the fan on when the AC goes off, the now liquid water sitting on the coil evaporates back into the air and gets blown back into the house. And that raises your indoor humidity. The graph below shows what happened when I did this in my home.

That setting is to keep the fan in the “On” position rather than “Auto.” (See my full article on this for all the details and data from a little experiment I did in my house.)

Turning the thermostat down when it’s too humid indoors

Southerners who go north in winter find it to be too cold. Northerners who go south in summer also find it to be too cold. So many buildings in the South are kept way too cold.

Why? Often it’s because the building lacks adequate humidity control. If it’s too humid indoors, you feel uncomfortable. It feels “sticky.” So people head to the thermostat and knock it down a few degrees.

This is a mistake for several reasons. First of all, it doesn’t solve the comfort problem. Yes, a lower setpoint causes the AC to run more, which makes it dehumidify more. But you still may end up with a higher relative humidity because the temperature is lower. So you end up feeling cold and clammy.

Another reason it’s a mistake is that you can cause serious damage to a house by keeping it really cold in a humid climate. You can read about that and more in my article titled 10 Consequences of Keeping Your House Really Cold in Summer.

And that’s not all…

The mistakes above are things homeowners do wrong. There’s another set of mistakes that installers and technicians make with the settings that aren’t easily accessible to homeowners. I’ll cover those another time.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can follow Allison on LinkedIn and subscribe to Energy Vanguard’s weekly newsletter and YouTube channel.

Related Articles

How NOT to Use Your Heat Pump Thermostat

This Thermostat Setting Can Cost You Money and Make You Sick

The Easy Way to Switch to a Heat Pump

Comments are welcome and moderated. Your comment will appear below after approval. To control spam, we close comments after one year.

If it’s not too humid but feels warm in the house, the fan on setting does a good job filtering the air with minimal electricity use. When you combine that with an open window or two (or a crawlspace vent that normally should be closed), it behaves like a whole house fan.

Stacy: Yes, that can work, but the key is to keep an eye on the outdoor dew point. Here’s my article about what threshold works best for that:

When Is the Humidity Low Enough to Open the Windows?

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/when-is-the-humidity-low-enough-to-open-the-windows/

There are some thermostats with “intelligent” heat pump recovery that try to avoid the use of auxiliary heat after night set backs. I can’t testify to how well they work, but one might consider them if they prefer night setback for “comfort” reasons (sleeping with a heavy blanket).

Roy: I also have no experience with those thermostats, but these adaptive recovery thermostats have been on the market for quite a while. The idea is that they monitor indoor and outdoor temperatures and start the heat pump earlier to use more compressor heat when recovering from a setback. They would do no good in my house, though, because my heat pump is about 30 percent undersized.

Some heat pump manufacturers prefer that you run the compressor when it is cold out since it helps prevent refrigerant from migrating to the compressor when it is cold without requiring a sump heater which also wastes energy. If it gets too cold, the system will protect itself as necessary.

Excellent point, Roy.

Allison, I just added a new term to my talks with new clients. There was a time when discussing tighter homes I would talk about building a “boat”, alluding to being water tight. Now I have upped the game to building a “submarine or space ship”. Whereby, I am responsible for engineering all indoor air quality into my systems. Humidity controls, contaminants, make-up air, etc. Seems to be well received.

T

Sounds good, Tom!

In the winter I have our temp set at 73 during the day and then it drops to 65 at 8:30 as 73 is too warm to be comfortable sleeping. Then it kicks back up in the morning. Now if it reaches 65 that depends on outside temp etc. On a cold day the 2nd stage heat will kick in for a bit during that warm up period. (I keep forgetting to disable the 2nd stage and just let it run on 1st) Our indoor humidity is generally around 50%. I am in TX and the humidity and dew points are generally always high despite what many think it’s actually like here.

In the summer the AC is set to 74 continuously and the humidity is still around 50%.

Now the question is are we comfortable at that temp and humidity in the summer. The answer is no. We would prefer it cooler. Now if I side step to the workshop which I can usually get it to around 75* in the summer if I keep it cooled. It is far far more comfortable than it is in the house. The reason being is that the humidity in the shop will generally be in the 20s. The minisplit does an excellent job of removing pretty much all the moisture possible from the shop. Despite many saying they do such a poor job at humidity removal. And it’s a leaky metal building.

Now if I could keep the humidity in the house closer to that number I’d be super comfortable at 75. I have an absolute hatred for humidity. I am far more comfortable year round when the humidity is in the 20s to mid 30s. My sinuses do far better when it’s dry as well. I guess I’m the oddity but…

As for opening windows… That’s a rarity here that is only possible in the early spring (northeners would call it their summer weather) and late fall and a few days in the winter. Dew points are only in the 50s with the odd cold front and then it’s only for a day or two usually as the gulf moisture gets pulled up by the front. And our nightly lows are 80* just before the sun comes up while it’s still in the 90s after midnight. The Texas chamber of commerce doesn’t tell you how bad our weather is when they want you to move here…

For a little background I grew up in Hawaii and the humidity was bad year round. The only place with AC was the mall… I as well as many others had so many ear infections that were caused by the high humidity it’s not even funny. Many of the houses now have AC and friends that are there have said the the dry air for sleeping has made it an issue of the past.

Good artical, and I practice most of the suggestions. My thermostat allows me to shut off the automatic emergency heat setting that will engage the elements if the temperature drops below 4 degrees of the target. Knowing this, I can go to the panel and manually engage the emergency heat if the temperature gets too uncomfortable. I live in Texas, and the temperature has to get into the 20s before emergency heat is needed.

I always recommend setback for gas burning appliance because the efficiency is always the same whether you use fallback or maintain a set temp 80%, 95% etc. But for air source heat pumps I usually recommend one set temperature and leave it. The morning recover would be at the coldest part of the day and the heat pump’s efficiency will be the worst. I’ve also seen where if you have staged or modulating heat pumps, and when they are not working full bore and if you wanted to go down the refrigerant and psychrometric path you will see the outdoor coil doesn’t get quite as cold, leading to less frost/ice build up and hence less defrost and ultimetly more efficient.

I have Warmboard in the floor, Nest thermostats (adaptive), and a Heat Exchanger coming off the DHW tank on Outdoor Reset Temperature control to heat the water going through radiant floor. The Nest thermostats show a call for heat most of the time when it drops below 40F (here in Zone 6A). It took me a while to calibrate the ODTR curve – because you want to barely keep up with the energy loss from the building. Under-sizing things works great – you just need to a simple energy balance.

Allison, you really need to stop calling electric resistance heat “100% efficient”. It is very misleading. Sure the electricity that shows up at your home can be converted to heat with little loss but that electricity is produced at a power plant that is far from 100% efficient. When you factor in transmission losses, that electric resistance heat is more like 30 or 35% efficient, 1/3 the thermal efficiency of a condensing furnace.

David: I think most people think of energy efficiency in terms of what happens onsite only. I’ll grant you that it’s an incomplete picture. Site and source energy are different things that have different efficiencies, and in the big picture, yeah, strip heat is not 100 percent efficient.

But whenever I mention that, it’s always in the context of contrasting it with what a heat pump can do with the same electricity. I would never tell someone to use electric resistance heat because it’s more efficient than a condensing gas furnace.

I did just expand on this subject in a new article, though, and will link to it when it comes up in the future.

Is Electric Resistance Heat Really 100 Percent Efficient?

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/is-electric-resistance-heat-really-100-percent-efficient/

David, I agree that there are many losses that go into electric production. However, if most of your electricity is generated on-site by PV, wind, or micro-hydro, those losses are minimized. And don’t forget too, about the energy that goes into mining NG and LP and losses on their way to your home. Losses may be relatively small, but they have a greater environmental impact, affecting health and safety. “The drilling and extraction of gas from wells and its transportation in pipelines results in the leakage of methane, the primary component of natural gas. Methane is 34 times stronger than CO2 at trapping heat over a 100-year period and 86 times stronger over 20 years.” (Source: https://www.ucsusa.org/resources/environmental-impacts-natural-gas). Plus, gas will only become harder to come by, making renewables more and more appealing. So yeah, Allison’s “resistance heat is 100% efficient” may only be true in a 100% renewable world, but we’ve gotta try to do better than non-renewable, health and planet harming gas, don’t we?

Great piece! I’d also like to add the danger in cold climates with set back thermostats at night, resulting in a spike in relative humidity, resulting in heavy condensation on cold surfaces (windows). We had a client who rotted out their new windows over the course of just 4 years combining heavy curtains with aggressive nighttime winter setback.

Michael: Wow! That’s some serious condensation…and a bad combination.

Setbacks reduce the temperature but don’t change the amount of water vapor in the indoor air. That results in the increase in relative humidity you mention. It also lowers the surface temperature of the glass, even without curtains. Put heavy curtains over the window, and the glass temperature drops even more since it’s insulated from the indoor temperature. But the water vapor in the indoor air can still come in contact with the glass.

Were the windows double or triple pane? Did they have a condensation resistance rating?