The Real Reason for HVAC Design — It’s Not Sizing

Many people seem to think HVAC design means you get a load calculation (Manual J in the ACCA protocols) so you know what size system to put in. Hey, that’s a great start. It’s way better than just using a rule of thumb or Manual E (for eyeball). You don’t really want to end up with a ginormous oversized air conditioner like the one above. (But I’m going to be a heretic here and suggest that oversizing isn’t as bad as some think, or at least not in one of the ways commonly believed. More on that in a future article.)

But there’s so much more to real HVAC design than simply finding out how much heating and cooling a building needs when it’s at design conditions. And we might as well start with the fact that my first statement is incorrect: The load calculation does not tell you what size system you need.

Load versus capacity

In an article I wrote last year, I went into detail about the difference between getting the load calculation results and sizing your heating and cooling system. You have to factor in the type of equipment you’re using, the efficiency of the equipment, the breakdown of the cooling loads into sensible and latent, and the difference between your design conditions and the conditions at which the equipment was rated. (Sensible load is related to changing the temperature; latent load is the part involved with removing moisture.)

But it really boils down to a difference between load and capacity. Heating and cooling loads are the amount of heating and cooling in BTU per hour (Watts for most places outside the US) that a building needs. Capacity is how much heating or cooling a piece of equipment can provide. Just remember that loads have to do with the building and capacity has to do with heating and cooling equipment.

Of course, there are three types of loads, but for design purposes, we use the design loads, which are based on design conditions. (The other two types are part load and extreme load.)

So, the load calculation is the first step. It leads to sizing but doesn’t give it to you right away. (Be careful reading those Manual J reports!) The second step is equipment selection (Manual S in the ACCA protocols), where you take into account those factors I mentioned above. It’s an important step and more involved than just reading the load off the Manual J report.

But even that isn’t the most important part of full HVAC design.

The dominance of distribution

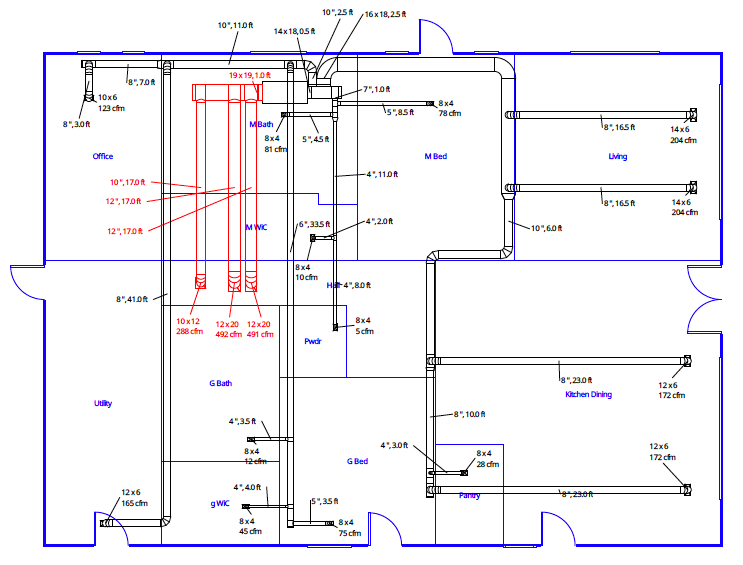

Calculating the heating and cooling loads is the easy part. Even selecting equipment is straightforward. Once you know the loads and have made decisions about the type of equipment (furnace & AC, heat pump…), getting the right capacities isn’t hard. But unless you’re using ductless mini-split heat pumps (a great choice, by the way), the next step is in many ways the most difficult and the one that dooms many projects. That is, designing the distribution system to make sure the house gets the right amount of heating and cooling delivered to the rooms. (We focus on air distribution at Energy Vanguard, so if you’re doing hydronic heating and cooling, you should talk to someone like my friend Robert Bean at Healthy Heating.)

Designing a good distribution means looking at a lot of variables:

- Placement of supply and return vents

- Location of air handler

- Framing obstructions

- Types of fittings

- Type of design: trunk-and-branch or radial

- Location of ducts (conditioned or unconditioned space)

- Proper air flow, both total through the system and the amount to each room

See my series on duct design to get a feel for it. There’s a lot that goes into it!

When you do it properly, you get a true system. Many homes just get a bunch of components that appear to be a system but really aren’t. Sadly, the bar is really low for heating and cooling systems. Since so few systems get true design, not many people know what they’re missing. If the house stays relatively warm in winter and cool in summer, it gets over the low bar.

But here’s what a good HVAC system provides:

- Comfort

- Indoor air quality

- Humidity control

- Quiet operation

- Durability

- Efficiency

As I write this, I’m sitting in our new office in Decatur, Georgia. We have our own system for the office, which is great. We don’t have to fight over the thermostat with other businesses in the building, as we did in our previous office. But the system is oversized. It’s loud. And it short cycles. We get blasted with hot or cold air for a few minutes. Then it goes off until the office starts getting a bit uncomfortable in the other direction, when it kicks on again.

The good news for us is that we’ve gotten permission from the building owners to replace the system we have with a Mitsubishi system consisting of a ducted mini-split for the two back rooms and wall-mounted ductless units for the front. We’re also getting an Ultra-Aire ventilating dehumidifier for the office. Stay tuned for an article about the installation once we get it all done.

The real reason

So, back to the original question of the real reason for HVAC design, you can see now that it’s a lot more than just proper sizing. That’s certainly important. But more important than proper sizing is making sure the HVAC is a true system, not just a bunch of components pretending to be a system.

Related Articles

What a Load Calculation Does NOT Tell You

The Basic Principles of Duct Design, Part 1

The 3 Types of Heating and Cooling Loads

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 19 Comments

Comments are closed.

Congrats on your new office..

Congrats on your new office… but if this building has an HVAC system that is not designed properly, would I be wrong to think the building envelope is just as bad?

Yes, you’re right, Armando.

Yes, you’re right, Armando. The building enclosure isn’t great. Fortunately, most of our walls are adiabatic. But the one that isn’t is uninsulated CMU with single pane, metal frame windows. That and the ceiling are where almost all the load comes from. But a better HVAC system will help us make up for the enclosure deficiencies. Not ideal, but even in its current state, our new office is a gazillion times better than our old one!

So basically you’re saying

So basically you’re saying that your new office gives off a hipster 70’s trendy vibe? 😉

Serious question: How often do you guys recommend a complete tear out of the existing ducts?

The real reason for HVAC

The real reason for HVAC design is – comfort. The reason most builders have turned to moving air is – it’s cheaper. Moving air (even warm air) always cools humans – it’s how we’re created. It is cheaper for builders to install oversized moving air systems than it is to construct air tight, super-insulated, well-engineered buildings (passive solar/solar siting, windows for views and illumination instead of the “money view”, etc.) Until customers are really concerned about long-term operating costs, true comfort, and practical day-to-day living (i.e., buy differently), I see little change.

Yep. Comfort is number one in

Yep. Comfort is number one in the list above of what you get when the HVAC design is done right.

You beat me to it.

You beat me to it.

You are right on with this

You are right on with this comment, my concern for building more efficiently is that it is possible to build energy efficiency into a structure and do so affordably, however the market today tells us that we have to have this or that to green build a home when we do not have to have such things, everything we need is already within the local marketplace of construction materials. My concern when looking at the HVAC system is to first know my building losses and then consider the air volume and the latent heat capacity. With an energy efficient design I always calculate the losses for the lowest winter temperature and my average summer time temperature, I want to know the base load in terms of Btu and Kilowatts since I might be adding renewable energy to the design also.

Love your article, but you’re

Love your article, but you’re missing one vital component of an HVAC system — indoor air quality. A properly-sized HVAC system, sealed ductwork and with quality filtration can remove dirt, spores and other contaminants from the indoor air.

What? It’s in the list, right

What? It’s in the list, right after comfort and before humidity control. (OK. Yeah, I did just add those two after your comment came in.)

Allison, another great blog.

Allison, another great blog. I think we spoke a couple of years ago about using an Ultra-aire dehumidifier for my home in coastal North Carolina. I am using the 70H for about 2000 sf and it works perfectly. I have a remote humidistat mounted next to the intake vent up near the ceiling of my three story home. The output is ducted down the elevator shaft wall as a means to recirculate the warm air down to the ground level stair-well to a grill on the wall. I set it for 45% RH and it never deviates more than a couple percent all year round. It is most effective right now as we are in the swing months before the cooling season starts (no AC or heat running). This is a timely topic.

I am planning to hire you to

I am planning to hire you to figure out the HVAC system for my new build in Arizona. I’m still in the design stage of the house but I don’t know what I don’t know, so how do I plan the framing? It’s a catch-22. I can’t get the HVAC design until the house is designed, but I can’t really design the house without knowing where to leave room for ductwork. I’m spending weeks trying to redesign the house to move the stairway ASSUMING I should have a duct run down the center with one long run and branches (centipede?). But, I might be better off with a ductopus, done correctly or course. I do know I’ll have two systems, because of the size of the house and the fact that it’s in the low desert and will have a finished walkout basement. Hopefully moving the stairway is necessary, because it’s a lot of work on the redesign and so far isn’t leading to pleasing floor plan.

Debbie, I was in your

Debbie, I was in your position not all that long ago. I, too, had chicken-and-egg framing/HVAC decisions to make. Energy Vanguard just recently finished my design, and I think it came out rather well and takes all of my considerations and tradeoffs into account. One piece of advice I would offer you: get them involved sooner rather than later, even if you have not nailed down your exact framing layout. Allison offered me that advice early on and I wish I had taken it sooner than I did. Nevertheless, I was pleased at how well Andy and Allison worked with me to get me what I needed.

I did contact Allison early

I did contact Allison early on but he said he couldn’t do anything until I had the design completed. 🙁 All I asked was for an estimate as to how much room to leave for the main trunk. Maybe that was the wrong question. I did tell him I absolutely want him to do the design, but I guess I can understand his not wanting to give out that advice when all I had was the square footage and the fact that two systems will be needed. It would have been nice to know though because I had 8 feet and since I didn’t know if that will be enough, I redesigned the stairway and some adjoining rooms to get more area. The redesign isn’t as nice as the original. I’m not the architect so once I get it all figured out in my mind, I will turn it over to the architect. I really can’t go to Allison before that because the architect might make huge changes. I should probably negotiate a redraw for issues like this.

Did you have an issue with where to put the stairway?

Debbie,

Debbie,

I didn’t have a stairway issue, I had an orientation issue. We are using I-beam trusses: running ducts perpendicular to them is problematic so I needed ducts to fit within the bays between them as much as possible. But it raised the same question — I wanted to know about duct sizes early on.

The first step in the design is to calculate the heating and cooling loads (“Manual J”). Not until the loads are known can zones be determined, equipment selected, CFM of flow to each room be determined — and then the delivery system (aka ductwork) be designed.

The good news is that the Manual J depends on things you probably already know like room size, envelope construction, glazing, and so forth. (Maybe also stairwell location; I’m not sure.) Once you know e.g. how many CFM will be required, and basically where ducts might go, you can do some guessing as to what the max size of the duct might be.

One happy discovery in my case: Like you, I was “sure” that I’d need two zones. However, the Manual J “adequate exposure diversity” (AED) calculation showed that I could get by just fine with one zone.

My suggestion: talk to Allison and see if it’s reasonable in your case to do your Manual J first, and then an A-B (or A-B-C) comparison between duct alternatives to help you decide on a layout. Of course, this presumes that the details of your room sizes, volumes, glazing, building orientation, etc. are known.

All the best,

Jeff

Thanks Jeff. Allison reached

Thanks Jeff. Allison reached out to me, but I do think I’m still too early in the preliminary stages so I’ll have to get some things firmed up first.

Another possible issue

Another possible issue related to equipment sizing is “recovery”. If you like to set up to set back temperatures for comfort or energy savings, a “properly” sized system may have trouble recovering in a reasonable amount of time under extreme outdoor conditions. So do you size to minimize cycling during normal operation, or to minimize recovery times between different occupancy periods? One solution that helps all of these issues is multi-capacity systems (2-stage or variable-speed compressor). I much prefer them over single-capacity systems due to comfort, but the energy efficiency is generally higher also.

Ever hear someone say

Ever hear someone say “Wrightsoft Manual J report says it needs 2.7 tons of A/C”. They don’t look at the sensible and latent loads…and rarely have the correct SHR entered (Can you say software default). Then equipmemt is selected based on AHRI temperature criteria, not local design temperatures. Without knowledge, it’s just another puece of software…

Have you ever priced a Manual

Have you ever priced a Manual J calculation?! So much cheaper to do the Ole’ Manual E!

Great article, Thanks Allison

Bigger is not always better!

Bigger is not always better! Especially with high efficiency installs these days