10 Consequences of Keeping Your Home Really Cold in Summer

I briefly worked at a dry cleaning shop in St. Louis a long time ago. It was December, and we had a bout of super cold weather one week. The temperature dropped to 0° F at night and got up only into the teens during the day. I worked inside where the temperature was always nice and warm, but the delivery guy had to go out in the cold every day. Before the cold front came through, the daytime temperature was in the 30s and 40s Fahrenheit, I think, and he’d go out with no jacket, just a short sleeve T-shirt, pants, and shoes. When the daytime temperatures dropped to the teens, he put on a light jacket over his T-shirt.

Everyone has a different sense of temperature. My coworker was a large guy whose job, aside from driving, kept him moving. He needed a lot of cooling. I, on the other hand, had trouble keeping warm with my 6’2″ 160 pound body. In my mind, I could grasp the concept of him not being cold, but my body shivered to see him outside on those cold days. I imagine he was a person who, in summer, would turn the air conditioner thermostat way down.

And that’s our topic for today. Apparently, some people like to have their air conditioners set to keep the house really cold. Like 68° F cold. I’m not here to judge your thermal preferences. Everyone’s internal furnace runs at their own internal setpoint. But if you set the AC thermostat really low like that, there may be consequences. Here are the main potential problems you should be aware of next time you head for the thermostat.

1. Growing mold

As I’ve written here many times, the key to preventing “accidental dehumidification” is to keep humidity low or surfaces warm. The colder you keep the indoor air in your home, the colder the walls, ceilings, floors, and windows will be. When water vapor from the air gets into the porous materials in those building assemblies, you have an ideal place to grow mold.

Some of that mold may be visible inside your house, but you may well end up with an invisible mold problem that still affects your indoor air quality. The photo above shows mold growing on the back side of the drywall on an exterior wall. This can happen even if the humidity in the house is low because humid outdoor air can leak into the wall cavities if they’re not sealed tightly.

2. Rotting your house

Curt Kinder, an HVAC contractor in Jacksonville, Florida and a longtime commenter here in the Energy Vanguard Blog, talks about houses he’s seen “totaled” by the thermostat set too low. That moisture from outdoors leaking into the walls, floors, and ceilings can rot the wood in addition to growing mold.

3. Condensation on your air conditioner vents

Keeping the house colder means the metal AC vents will be colder. Even with less humidity in the house, those surfaces may be below the dew point. See my article from a couple months ago, Why Do Air Conditioning Vents Sweat?

4. Condensation on your ducts

With the air conditioner running longer, the ducts will get colder, too. If they’re in an attic, crawl space, or basement with high dew point air, they’re likely to be dripping. If the attic ducts are buried in insulation, they’re even more likely to have condensation, which then can drip down onto the ceiling and create ugly water spots…and possibly grow mold.

If your ducts have paper-faced insulation on them, as shown above, that condensation also can grow mold.

5. More duct leakage and infiltration

The more your air conditioner runs, the more it leaks. If you have a well-sealed duct system, this isn’t that big a deal. If your ducts are leaky, they’ll be leaking for a longer amount of time each day to keep your house cold. If you have unbalanced duct leakage, you also get more infiltration, so it hurts you twice in that case.

6. Larger air conditioning capacity needed

In our HVAC design work, we typically use the indoor design conditions recommended by the Air Conditioning Contractors of America (ACCA): 75° F and 50% relative humidity. There’s usually a little cushion in the capacity we specify but probably not enough to get your house down to 68° F when the outdoors is at your local design temperature.

7. Reduced energy efficiency

With colder air in the house, the air conditioner gets colder air coming into the system for further cooling. That means there’s less heat for the air conditioner to remove from the return air, resulting in an evaporator coil that gets colder. John Proctor showed that colder evaporator coils lead to lower efficiency. (He was discussing one of the flaws with zoning bypass ducts, but the same principle applies no matter what makes the coil colder.)

8. Increased energy use

This isn’t the same is number 7. Even if somehow the AC was magically able to run at the same efficiency when keeping the house colder, it still uses more energy because it runs more.

9. More frequent filter changes

First, the good news: If you have good filtration set up with your air conditioner, you’ll have cleaner air because the air will be cycling through the system more often. The bad news, though, is that you’ll have to change the filters more frequently. And if you don’t, your air flow will drop, possibly freezing up your coil or damaging the compressor.

10. More energy use in your heat pump water heater

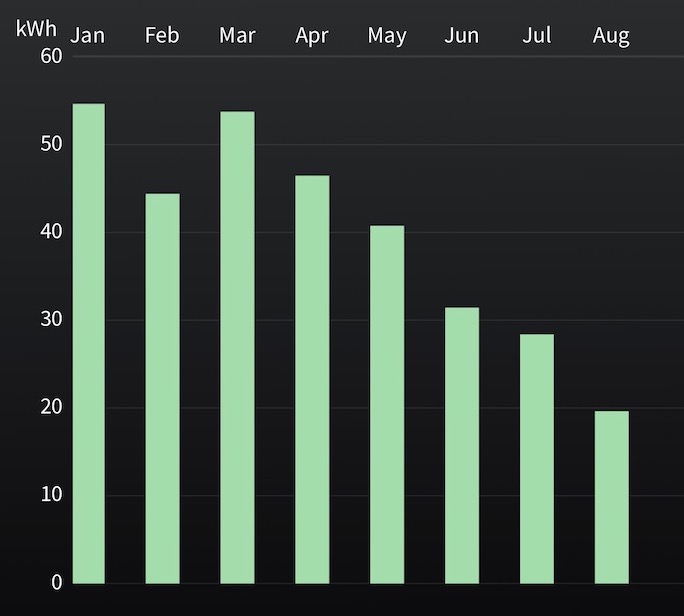

OK, maybe you don’t have a heat pump water heater (yet), but I got one last September and I love it. It’s in my basement, and I’ve been watching the energy use change with basement temperature. I’ve got a full article on this coming soon, but here’s a sneak peek at this year’s energy use for my Rheem Performance Platinum.

That decline in monthly electricity consumption is due solely to higher temperature in the basement. I haven’t measured the hot water we’ve used, but if anything, that’s gone up because I’ve been working from home since 13 March. We average less than 1 kilowatt-hour (kWh) per day in the summer and close to 2 kWh per day in the winter.

Advice for those who like it cold

If you’re one of those people who has to have it cold, you should be aware of the potential problems I’ve listed above. Still want that thermostat at 68° F? Pay attention to the indoor and outdoor dew points, especially in comparison to the temperature you’re keeping your house at. If you keep the house at 68° F and the outdoor dew point gets up into the 70s Fahrenheit every day, you may have started a biology experiment inside your walls. A moisture meter* can tell you if your walls are too wet. To avoid a wet, rotting house, you need a really good air barrier on the outside of your walls to keep that humid air out. Also, check your supply vents and ducts for condensation. Of course, dropping the indoor air temperature with air conditioning isn’t the only way to keep cool. Combining AC with air movement from fans might be enough to get your house out of the danger zone.

When I moved to St. Louis for grad school at Washington University in the summer of 1983, I would have loved to have any air conditioning at all. Instead, I moved into an old apartment near the Loop and had to keep cool with only a fan during a hot summer when the temperature hit 103° F. But I sure was happy when I discovered the milkshakes at Ted Drewes!

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and founder of Energy Vanguard. He is also the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Related Articles

Accidental Dehumidification – A Preventable Mess

Make Dew Point Your Friend for Humidity

Buried Ducts Risk Condensation in Humid Climates

* This is a TruTech Tools affiliate link. You pay the same price you would pay normally, but Energy Vanguard makes a small commission if you buy after using the link.

Photo of woman freezing by Jerzy Kociatkiewicz from flickr.com, used under a Creative Commons license.

NOTE: Comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear below until approved.

This Post Has 13 Comments

Comments are closed.

I’d like to bring up the

I’d like to bring up the strategy of whole home dehumidification as a way of lowering the risks you outline in this article. Thermal comfort can be gained at higher thermostat set points with drier indoor air. Air sealing the envelope could be another strategy to combat many of the issues listed above as well.

Now this is spooky cool. I

Now this is spooky cool. I was about to add the exact same comment. I install dedicated dehumidifiers in all of my coastal NC homes to supplement the normal HVAC system, keeping RH >50% at all times. It runs occasionally during the cooling months, but really works during the swing or shoulder months when AC is not used or seldom used. In our house, we are comfortably running AC at 77 or 78 degrees (dry heat, Arizona thing), thus taking some load off of the AC system.

As to sealing the exterior, any air movement within the walls is counterproductive and dangerous from a mold perspective. My blower door numbers are in the .5ACH50 range. For air quality, we add a 6″ fresh air duct with filter and temperature/humidity controlled blower set to 120cfm. This fresh air is added into the conditioned attic space to mix with conditioned air prior to entry into living spaces.

Nathan, yes, a dehumidifier

Nathan, yes, a dehumidifier will solve some of problems (e.g., sweating supply registers), but it doesn’t help with mold growing inside the walls because of outdoor air leaking into the cavity. That requires air sealing the exterior sheathing, which is why I wrote this in the last section:

To avoid a wet, rotting house, you need a really good air barrier on the outside of your walls to keep that humid air out.

Unfortunately, that’s hard to do on existing homes.

It’s worth pointing out that

It’s worth pointing out that a dehumidifier will further blow up the energy budget. Moreover, dehumidifiers have less capacity and higher operating cost at lower ambient temperatures. OTOH, anyone who sets their t’stat in the 60’s apparently doesn’t care about energy efficiency. But they should care about mold and house rot. And as Allison noted above, a dehumidifier does nothing to mitigate those risks. If anything, it will exacerbate the problem by increasing vapor drive.

David, your points, as always

David, your points, as always, are well taken. My dehumidifier hour per day usage is supplemental during cooling months (one or two hours as most) and gets some help with electricity usage by running thermostat comfortably higher. A 70 pint dehumidifier draws around 600 watts.

As to vapor drive, I spend my first insulation dollars on sealing the “shell of the egg”. I do not want hot moist outside air meeting cool inside air anywhere if possible.

Great topic Allison. Thank you.

Good article, Allison.

Good article, Allison. Helpful to educate homeowners on that very issue right here in St. Louis. Most understand it well and keep it in the right range, but frequently see folks try to keep the tstat at 68 – 65 in at least two cases (sorry, that’s not in the warranty). Your ending did make me think of my air condition-less days at Fort Leonard Wood in days gone by – sadly, no Ted Drewes in sight out there. I had forgotten you went to Wash U. – I’ll bet despite the heat you had a great time (and great education).

Dave, I was hoping someone

Dave, I was hoping someone from St. Louis would see this article and know about Ted Drewes! Yes, I went to Wash. U. but can’t say I got a good education there. Not because of the school, though. I wasn’t ready for grad school then so I dropped out after about six weeks. That’s why I was working at a dry cleaners’ in December ’83. Eight years later, I did go back to grad school at Florida.

Very interesting article, I

Very interesting article, I am about to head out to investigate this exact problem. This client keeps his house at 63 deg F in the summer our daily temperate is around 80 to 90deg F. the client thinks he is suffering from the effects of mold. The house was built in 2000 and vapour barriers are on the inside in Montreal. I think there is condensation inside the walls. Do you agree?

Regards

and thank you for all your interesting blogs

Ivan Mose

Ivan, yeah, that sounds like

Ivan, yeah, that sounds like a recipe for a lot of condensation inside the walls. With the plastic vapour barrier behind the drywall, none of the water vapour has a chance to diffuse through the drywall and provide a little bit of drying. It all gets stuck in there, and with the house at 17° C, they’ve got a really cold surface to collect it.

Please include this in your

Please include this in your book as it is becoming more common. I spend the bulk of my days on service calls. Among the younger generations it no longer shocks me to see a 68-69 degree set point. Additionally, the set points are often lowered to 65-66 degrees at night.

Recently I was in a home

Recently I was in a home where the thermostat was set at 68 and the customer asked why there were drops of water dripping from the registers. Upon further inspection I found the fireplace damper open introducing the hot humid Florida air into the living room. The homeowner was not aware of the damper. Of course I sealed the fireplace with plastic sheets before doing the test and he was amazed at how the sheet bulged even with the damper closed. I don’t think I changed his mind on his thermostat setting but maybe on how the problem is created.

I’m glad to see this article.

I’m glad to see this article. I have a customer whom I have attempted to explain this scenario to. Stat set to 64°, back door open, swamp in backyard, she asks my why water is running down the bathroom walls and tells me six months ago a mold remediation company had all the walls opened up. Nightmare scenario.

Howdy!

I live in Austin, TX and we have a few months of high humidity and high outside temps. I’m getting ready to design a new home and I have been battling with this issue. My girlfriend of over 20+ years (stopped counting) likes it around 68 to sleep…me not so much. Our new house will have 2 zones, a his and hers zone if you will (rooms on opposite ends of the house), and likely 2 geothermal HVAC systems in the 3000 sq. ft. home. After reading this helpful article, I am leaning to doing an Insulated Concrete Form (ICF) house. Will that alleviate these potential risks, along with a dehumidifier? Also, due to PTSD, I can’t sleep with any noise or I wake up…is there a way to design ducts/returns/equipment to be completely silent? It is so annoying, I can’t even sleep with a ceiling fan on.

Here in Austin, they love flex ducts (I don’t like them – I have allergies up the ying yang), and most installers seem to cut corners on HVAC design and installation, or charge an arm and a leg.

Any suggestions will be greatly appreciated. I have just gotten so much conflicting answers, it is hard to sort.